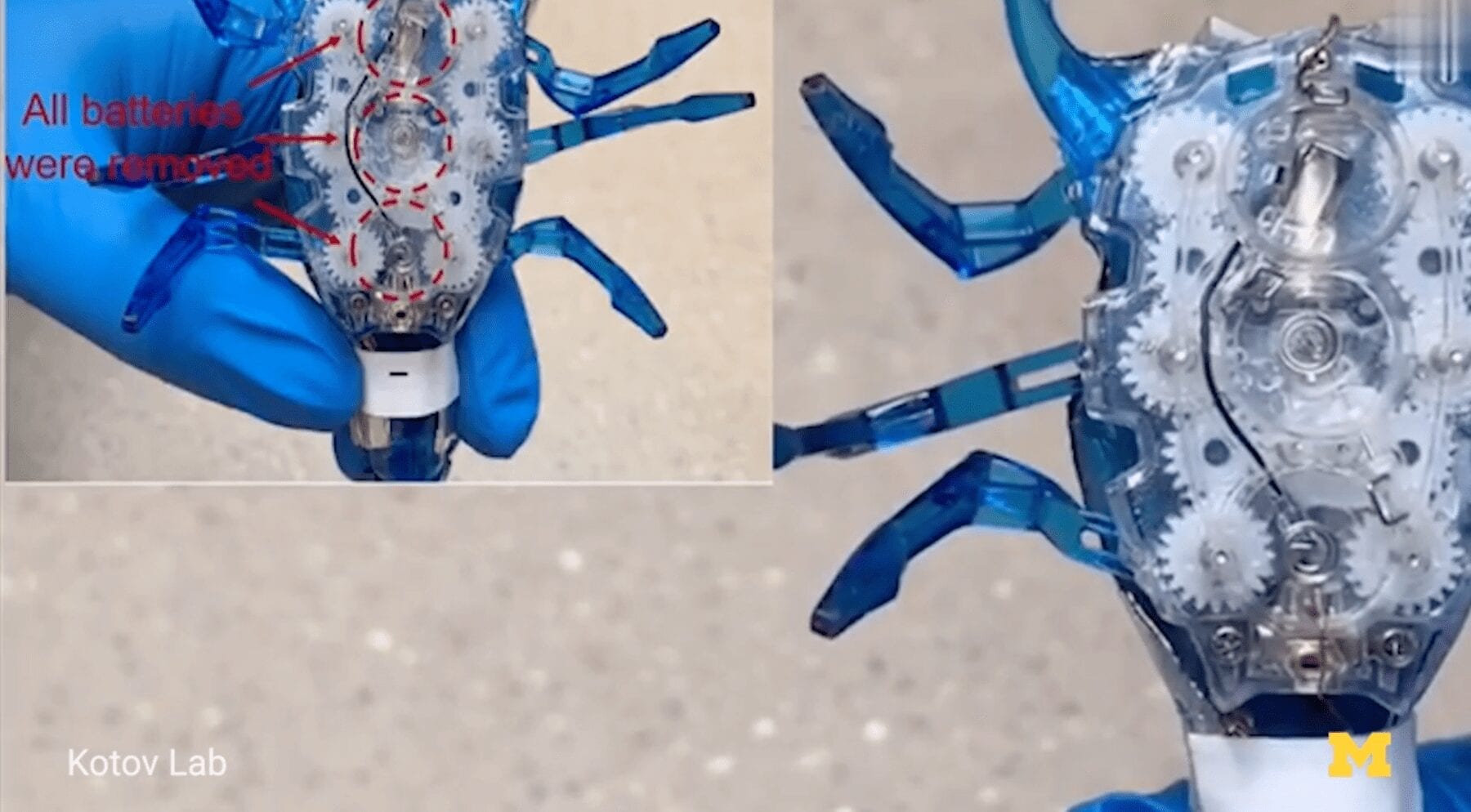

Novel application of 3D printing could enable the development of miniaturized medical implants, compact electronics, tiny robots, and more

3D printing can now be used to print lithium-ion microbatteries the size of a grain of sand. The printed microbatteries could supply electricity to tiny devices in fields from medicine to communications, including many that have lingered on lab benches for lack of a battery small enough to fit the device, yet provide enough stored energy to power them.

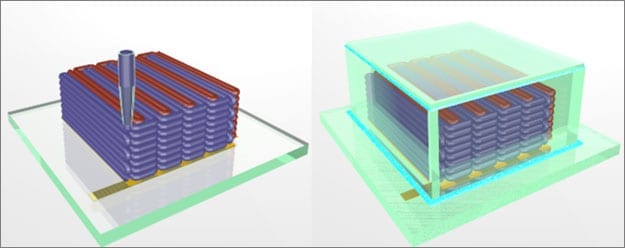

To make the microbatteries, a team based at Harvard University and the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign printed precisely interlaced stacks of tiny battery electrodes, each less than the width of a human hair.

“Not only did we demonstrate for the first time that we can 3D-print a battery, we demonstrated it in the most rigorous way,”said Jennifer Lewis, Ph.D., senior author of the study, who is also the Hansjörg Wyss Professor of Biologically Inspired Engineering at the Harvard School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS), and a Core Faculty Member of the Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering at Harvard University. Lewis led the project in her prior position at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, in collaboration with co-author Shen Dillon, an Assistant Professor of Materials Science and Engineering there.

The results were published in today’s online edition of Advanced Materials.

In recent years engineers have invented many miniaturized devices, including medical implants, flying insect-like robots, and tiny cameras and microphones that fit on a pair of glasses. But often the batteries that power them are as large or larger than the devices themselves — which defeats the purpose of building small.

To get around this problem, manufacturers have traditionally deposited thin films of solid materials to build the electrodes. However, due to their ultrathin design, these solid-state micro-batteries do not pack sufficient energy to power tomorrow’s miniaturized devices.

The scientists realized they could pack more energy if they could create stacks of tightly interlaced, ultrathin electrodes that were built out of plane. For this they turned to 3D printing. 3D printers follow instructions from three-dimensional computer drawings, depositing successive layers of material — inks — to build a physical object from the ground up, much like stacking a deck of cards one at a time. The technique is used in a range of fields, from producing crowns in dental labs to rapid prototyping of aerospace, automotive, and consumer goods. Lewis’ group has greatly expanded the capabilities of 3D printing. They have designed a broad range of functional inks — inks with useful chemical and electrical properties. And they have used those inks with their custom-built 3D printers to create precise structures with the electronic, optical, mechanical, or biologically relevant properties they want.

The Latest Bing News on:

3D printed microbatteries

- A 3D Printer On Every Desk? Why Companies Are Buying More 3D Printerson May 2, 2024 at 4:56 am

Entry-level desktop 3D printers saw record sales in 2023. It’s not the number of machines sold that’s surprising; it’s who’s buying them: businesses.

- Marriage of synthetic biology and 3D printing produces programmable living materialson May 1, 2024 at 5:00 pm

Between day one (left) and day 14 (right), plant cells 3D printed in hydrogel grow and begin flourishing into yellow clusters. (Image: ACS) Recently, researchers have been developing engineered living ...

- Best 3D printer deals: Start printing at home for $159on April 30, 2024 at 4:33 am

For now, though, there are a ton of great 3D printer deals you can take advantage of, which is why we’ve gone out and found some of our favorites and compiled them for you below. The Creality ...

- Affordable starter home is 3D-printed in just 18 hourson April 25, 2024 at 8:48 am

It's obviously relatively basic compared to other 3D-printed houses we've seen, like the more high-end Wolf Ranch models, though it's also around $400,000 cheaper, so is focused toward a totally ...

- World's biggest 3D printer unveiled in Maine may one day create entire neighborhoodson April 24, 2024 at 9:14 am

ORONO, Maine - The world's largest 3D printer has created a house that can cut construction time and labor. An even larger printer unveiled on Tuesday may one day create entire neighborhoods. The ...

- These 3D-printed homes take just 4 days to build — here’s how they could solve one state’s massive housing shortageon October 7, 2023 at 2:48 am

A recyclable 3D-printed home made from natural materials has been revealed to the public, and this may only be the beginning. The design is part of a project to create a “factory of the future ...

- 3D Printed Engine Gets Carburetoron August 30, 2023 at 2:11 am

3D printed materials have come a long way in the last decade or so as printers have become more and more mainstream. Printers can use all kinds of different plastics with varying physical ...

- Why 3D printed food is set to go mainstreamon May 3, 2023 at 3:36 am

3D food printing could also transform industrial-scale food manufacturing, according to Dr Vincenzo Di Bari, assistant professor in food structure and processing at Nottingham University. Instead ...

- 3D-Printed Rockets Set To Blast Offon June 30, 2022 at 9:31 am

Opinions expressed by Forbes Contributors are their own. I'm a journalist covering professional and industrial 3D printing. Relativity Space stage 1 3D-printed rocket being installed at Cape ...

- Can Solder Paste Stencils Be 3D Printed? They Can!on March 27, 2020 at 6:28 am

[Jan Mrázek]’s success with 3D printing a solder paste stencil is awfully interesting, though he makes it clear that it is only a proof of concept. There are a lot of parts to this hack ...

The Latest Google Headlines on:

3D printed microbatteries

[google_news title=”” keyword=”3D printed microbatteries” num_posts=”10″ blurb_length=”0″ show_thumb=”left”]

The Latest Bing News on:

Lithium-ion microbatteries

- Toyota, Argonne National Lab study lithium-ion battery recyclingon April 30, 2024 at 5:00 pm

Toyota Motor North America, Ann Arbor, Michigan, has entered a cooperative research and development agreement (CRADA) with the U.S. Department of Energy's Argonne National Laboratory to investigate ...

- Lawmakers demand transparency on Carmel lithium-ion battery storage facilityon April 30, 2024 at 4:57 am

Rep. Mike Lawler (R-17) is among those urging the planning board and the state to thoroughly investigate the environmental impacts of the proposed facility.

- ‘Battery revolution’? First US sodium-ion plant comes online.on April 30, 2024 at 3:51 am

The first sodium-ion battery plant in the U.S. started operations Monday, offering an alternative to lithium-based storage that currently dominates the market.

- Sodium-ion batteries from Michigan plant to challenge lithium’s gripon April 29, 2024 at 11:22 am

Natron Energy Inc. bills the facility near the Lake Michigan shore as the first full-scale U.S. plant for making sodium-ion batteries.

- Why are lithium ion batteries a hazard? What to know after Columbus LIB fire spurs evacuationon April 19, 2024 at 3:28 am

A Columbus tractor trailer fire caused by lithium batteries on Thursday has us asking: Why do lithium batteries explode? And can you recycle them?

- Get the facts on lithium ion batterieson December 20, 2023 at 9:54 am

From cell phones to cars to e-scooters and power tools, lithium ion batteries are everywhere. Local fire crews say they're seeing an increase in fires because of them. “They are really user-friendly, ...

The Latest Google Headlines on:

Lithium-ion microbatteries

[google_news title=”” keyword=”lithium-ion microbatteries” num_posts=”10″ blurb_length=”0″ show_thumb=”left”]