At 77, Jackson is a big man with big ideas.

A few weeks ago at the annual Prairie Festival in Salina, Kan. — a celebration, essentially, of true sustainability — I sat down with Wes Jackson to drink rich beer and eat delicious, chewy bread made from the perennial grain Kernza. The Kernza we ate was cultivated at the Land Institute, the festival’s sponsor and the organization Jackson founded here 37 years ago.

At 77, Jackson is a big man with big ideas. Clearly he was back then as well, when he became determined to change the face of agriculture from being dependent upon annual monoculture (that is, planting a new crop of a single plant each year) to one that includes perennial polyculture, with fields containing varieties of mutually complementary species, planted once, harvested seasonally but remaining in place for years.

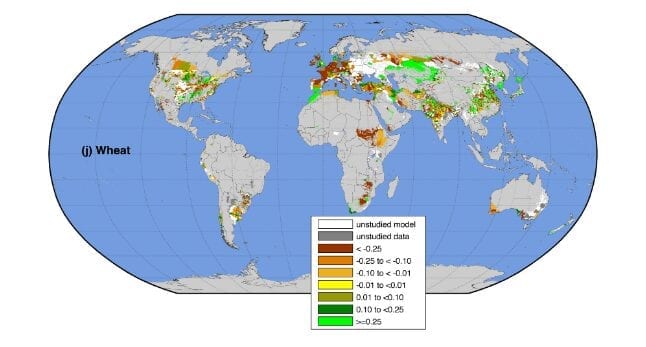

Jackson has a biblical way of speaking: “The plow has destroyed more options for future generations than the sword,” he says. “But soil is more important than oil, and just as nonrenewable.” Soil loss is one of the biggest hidden costs of industrial agriculture — and it’s created at literally a glacial pace, maybe a quarter-inch per century. The increasingly popular no-till style of agriculture reduces soil loss but increases the need for herbicides. It’s a short-term solution, requiring that we poison the soil to save it.

Annual monoculture like that practiced in the Midwestern Corn Belt is one culprit. It produces the vast majority of our food, and much of that food — perhaps 70 percent of our calories — is from grasses, which produce edible seeds, or cereals. For 10,000 years we’ve plowed the soil, planted in spring and harvested in fall, one crop at a time.

In an essay he published 26 years ago, called “The Worst Mistake in the History of the Human Race,” Jared Diamond theorized that this was essentially our downfall: by losing our hunter-gatherer roots and becoming dependent on agriculture, we made it possible for the human population to expand but paid the price in the often malnourishing, environmentally damaging system we have today.

That’s fascinating, and irreversible; barring a catastrophe that drastically reduces the human population, we’ll rely on agriculture for the foreseeable future. But if we look to the kind of systems Jackson talks about, we can markedly reduce the damage. “We don’t have to slay Goliath with a pebble,” he says of industrial agriculture. “We just have to quit using so much fertilizer and so many pesticides to shrink him to manageable proportions.”

Go deeper with Bing News on:

Sustainable agriculture

- North Eastern Region Farm Machinery Training & Testing Institute Teams Up with Shymal FPC & APART to Promote Sustainable Agriculture

North Eastern Region Farm Machinery Training & Testing Institute and Shymal FPC collaborated on an awareness program, promoting sustainable agriculture through DSR and zero tillage techniques ...

- Sustainable Agriculture: Morocco’s ADA, UNDP Join Forces to Strengthen Youth Entrepreneurship

The Agricultural Development Agency (ADA) and the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) signed a memorandum of understanding in Meknes on Friday, focusing on strengthening the ecosystem of youth ...

- Agricultural Extension Services Experts Canvass Adoption of New Technology to Drive Food Security

Experts have canvassed the integration of Artificial Intelligence and emerging relevant technological innovations into agricultural extension practices in order to improve agricultural production ...

- Georgia, FAO sign new $4mln project to boost sustainable agriculture, rural development

Otar Shamugia, the Minister of Environment Protection and Agriculture of Georgia, and Raimund Jehle, the representative of the United Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organisation in the country, on ...

- Agriculture Nets Market Projected to Soar to an Impressive US$ 18,242.6 Million by 2033

The global forecast for the agriculture nets market predicts substantial growth, with a market size estimated at US$ 10,679.8 million in 2023. The anticipated Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) of 5.5 ...

Go deeper with Google Headlines on:

Sustainable agriculture

[google_news title=”” keyword=”sustainable agriculture” num_posts=”5″ blurb_length=”0″ show_thumb=”left”]

Go deeper with Bing News on:

Land Institute

- Land O'Lakes is expanding flexible schedules for manufacturing employees

Land O'Lakes produces more than 300,000 pounds of cheese per day in Melrose, Minn., where some new hires were allowed to choose their own shift lengths and start times last year. Now more than 60 of ...

- Institute focuses on land stewardship to improve soil health

The Noble Research Institute is focused on land stewardship for improved soil health for grazing animal production with lasting profitability.

- Rural Georgia community battles railroad trying to take their land

An officer with the Georgia Public Service Commission says a private company can take land from 18 property owners in Sparta.

- 5 cities that will give you a house or land for free

According to the latest data from the Realtors' Land Institute, sales of American land increased 1.2% from 2022 to 2023, while its cost jumped 1.9%. Home prices hover around record highs in most ...

- Panel discusses affordable housing in Memphis

MEMPHIS, Tenn. (WMC) - Affordable housing solutions in the Memphis area were the focus of a group panel hosted by the Urban Land Institute on Thursday. The panel consisted of multiple ...

Go deeper with Google Headlines on:

Land Institute

[google_news title=”” keyword=”Land Institute” num_posts=”5″ blurb_length=”0″ show_thumb=”left”]