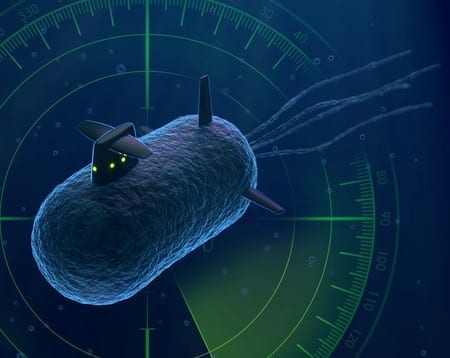

Credit: Barth van Rossum for Caltech

New technology may one day allow doctors to image therapeutic bacterial cells in patients

In the 1966 science fiction film Fantastic Voyage, a submarine is shrunken down and injected into a scientist’s body to repair a blood clot in his brain. While the movie may be still be fiction, researchers at Caltech are making strides in this direction: they have, for the first time, created bacterial cells with the ability to reflect sound waves from inside bodies, reminiscent of how submarines reflect sonar to reveal their locations.

The ultimate goal is to be able to inject therapeutic bacteria into a patient’s body—for example, as probiotics to help treat diseases of the gut or as targeted tumor treatments—and then use ultrasound machines to hit the engineered bacteria with sound waves to generate images that reveal the locations of the microbes. The pictures would let doctors know if the treatments made it to the right place in the body and were working properly.

“We are engineering the bacterial cells so they can bounce sound waves back to us and let us know their location the way a ship or submarine scatters sonar when another ship is looking for it,” says Mikhail Shapiro, assistant professor of chemical engineering, Schlinger Scholar, and Heritage Medical Research Institute Investigator. “We want to be able to ask the bacteria, ‘Where are you and how are you doing?’ The first step is to learn to visualize and locate the cells, and the next step is to communicate with them.”

The results will be published in the January 4 issue of the journal Nature. The lead author is Raymond Bourdeau, a former postdoctoral scholar in Shapiro’s lab.

The idea of using bacteria as medicine is not new. Probiotics have been developed to treat conditions of the gut, such as irritable bowel disease, and some early studies have shown that bacteria can be used to target and destroy cancer cells. But visualizing these bacterial cells as well as communicating with them—both to gather intel on what’s happening in the body and give the bacteria instructions about what to do next—is not yet possible. Imaging techniques that rely on light—such as taking pictures of cells tagged with a “reporter gene” that codes for green fluorescent protein—only work in tissue samples removed from the body. This is because light cannot penetrate into deeper tissues like the gut, where the bacterial cells would reside.

Shapiro wants to solve this problem with ultrasound techniques because sound waves can travel deeper into bodies. He says he had a eureka moment about six years ago when he learned about gas-filled protein structures in water-dwelling bacteria that help regulate the organisms’ buoyancy. Shapiro hypothesized that these structures, called gas vesicles, could bounce back sound waves in ways that make them distinguishable from other types of cells. Indeed, Shapiro and his colleagues demonstrated that the gas vesicles can be imaged with ultrasound in the guts and other tissues of mice.

The team’s next goal was to transfer the genes for making gas vesicles from the water-dwelling bacteria into a different type of bacteria—Escherichia coli, which is commonly used in microbial therapeutics, such as probiotics.

“We wanted to teach the E. coli bacteria to make the gas vesicles themselves,” says Shapiro. “I’ve been wanting to do this ever since we realized the potential of gas vesicles, but we hit some roadblocks along the way. When we finally got the system to work, we were ecstatic.”

One of the challenges the team hit involved the transfer of the genetic machinery for gas vesicles into E. coli. They first tried to transfer gas-vesicle genes isolated from a water-dwelling bacterium called Anabaena flos-aquae, but this didn’t work—the E. coli failed to make the vesicles. They tried again using gas-vesicle genes from a closer relative of E. coli, a bacterium called Bacillus megaterium. This didn’t succeed either, because the resulting gas vesicles were too small to efficiently scatter sound waves. Finally, the team tried a mix of genes from both species—and it worked. The E. coli made gas vesicles on their own.

The gas vesicle genes code for proteins that act like either bricks or cranes in building the final vesicle structure—some of the proteins are the building blocks of the vesicles while some help in actually assembling the structures. “Essentially, we figured out that we need the bricks from Anabaena flos-aquae and the cranes from Bacillus megaterium in order for the E. coli to be able to make gas vesicles,” says Bourdeau.

Subsequent experiments from the team demonstrated that the engineered E. coli could indeed be imaged and located within the guts of mice using ultrasound.

“This is the first acoustic reporter gene for use in ultrasound imaging,” says Shapiro. “We hope it will ultimately do for ultrasound what green fluorescent protein has done for light-based imaging techniques, which is to really revolutionize the imaging of cells in ways there were not possible before.”

The researchers say the technology should be available soon to scientists who do research in animals, although it will take many more years to develop the method for use in humans.

Learn more: Scientists Design Bacteria to Reflect “Sonar” Signals for Ultrasound Imaging

The Latest on: Ultrasound imaging

[google_news title=”” keyword=”ultrasound imaging” num_posts=”10″ blurb_length=”0″ show_thumb=”left”]- N.S. mom calls for better ultrasound access after private clinic reveals twinson April 27, 2024 at 1:00 am

A Halifax mother is calling for better access to hospital ultrasounds after she recently discovered she was having twins while receiving private care.

- SGMC Health Foundation funds cardiac ultrasound machineon April 26, 2024 at 5:00 pm

Demand for this imaging has surged due to an aging population with long-term health conditions. The new machine represents a quantum leap forward in cardiac ultrasound technology, offering ...

- Exo brings AI heart, lung apps to its hand-held ultrasound probeon April 24, 2024 at 6:10 am

The handheld ultrasound developer Exo has launched two new FDA-cleared artificial intelligence applications tied to its pocket-sized Iris probe, which made its own debut last fall. | The latest green ...

- International Contrast Ultrasound Society (ICUS) and Northwest Imaging Forums announce partnership to advance IV training for sonographerson April 23, 2024 at 10:41 am

The International Contrast Ultrasound Society (ICUS) and Northwest Imaging Forums (NWIF) today announced an educational partnership to help train sono ...

- ThinkSono Releases Real-Time DVT AI Training Solution for Butterfly Network's Handheld Ultrasound Deviceson April 23, 2024 at 7:01 am

LONDON, ENGLAND / ACCESSWIRE / April 23, 2024 / ThinkSono, a pioneering provider of AI-driven medical imaging solutions, is proud to announce the ...

- Ultrasound Devices Market is Set to Surpass Valuation of USD 11,229.9 Million By 2032: Astute Analyticaon April 23, 2024 at 5:30 am

The global ultrasound devices market surges, driven by rising chronic diseases, technological advancements in portability and imaging, and an aging population demanding accessible diagnostics. Growth ...

- Advancing high-resolution ultrasound imaging with deep learningon April 22, 2024 at 11:38 am

Researchers at the Beckman Institute for Advanced Science and Technology have developed a new technique to make ultrasound localization microscopy, an emerging diagnostic tool used for high-resolution ...

- Advancing high-resolution ultrasound imaging with deep learningon April 22, 2024 at 11:18 am

Ultrasound localization microscopy works by ... create spatial images of blood vessels at the microscale. The current imaging speed of ULM has limited its practical application as a diagnostic ...

- GE HealthCare launches new AI-enhanced ultrasound for women’s healthon April 18, 2024 at 10:49 am

(Nasdaq: GEHC) launched the Voluson Signature 20 and 18 ultrasound systems for women's health imaging applications.

- Ultrasound Devices Market Expected to Grow - with the rising prevalence of cardiac disorders expected to boost the market globallyon April 15, 2024 at 1:01 am

Dublin, April 15, 2024 (GLOBE NEWSWIRE) -- The "Global Ultrasound Devices Market Size, Share & Trends Analysis Report by Application (Cardiology, Radiology), Portability (Handheld, Compact), End-use ...

via Google News and Bing News