A statistical analysis shows how things really are heating up

ARE heatwaves more common than they used to be? That is the question addressed by James Hansen and his colleagues in a paper just published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Their conclusion is that they are—and the data they draw on do not even include the current scorcher that is drying up much of North America and threatening its harvest. The team’s method of presentation, however, has caused a stir among those who feel that scientific papers should be dispassionate in their delivery of the evidence. For the paper, interesting though the evidence it delivers is, is far from dispassionate.

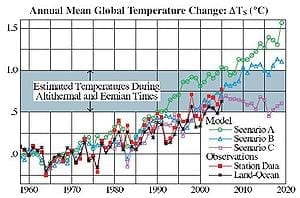

Dr Hansen, who is head of the Goddard Institute for Space Studies, a branch of NASA that is based in New York, is a polemicist of the risks of man-made global warming. Despite his job running a government laboratory, he has managed to get himself arrested on three occasions for protesting against those he thinks are causing such climate change. He clearly states in the paper’s introduction that he was looking for a way of conveying his fears to a sceptical public.

Some of that scepticism is connected with the fact that although changes in the climate will inevitably result in changes in the weather, ascribing any given event—such as a local heatwave—to climate change is impossible. Dr Hansen has therefore tried to go beyond the study of individual causes by demonstrating that what was once unusual is now common.

Longer, hotter summers

To do so, he and his colleagues took 60 years’ worth of data (the period from 1951 to 2011) from the Goddard Institute’s surface air-temperature analysis. This analysis divides the planet’s surface into cells 250km (about 150 miles) across and records the average temperature in each cell. The researchers broke their data into six decade-long blocks and compared those blocks’ statistical properties.

They looked in particular at the three months which constitute summer in the northern hemisphere (June, July and August). First, they created a reference value for each cell. This was its average temperature over those three months from 1951-80. Then they calculated how much the temperature in each cell deviated from the cell’s reference value in any given summer. That done, they plotted a series of curves, one for each decade, that showed how frequently each deviant value occurred.

via The Economist

The Latest Streaming News: Climate Change updated minute-by-minute

Bookmark this page and come back often

Latest NEWS

Latest VIDEO