Light can transmit more data while consuming far less power than electricity, and an engineering feat brings optical data transport closer to replacing wires.

In computers today, data is pushed through wires as a stream of electrons. That takes a lot of power, which helps explain why laptops get so warm.

“Several years ago, my colleague David Miller carefully analyzed power consumption in computers, and the results were striking,” said Vuckovic, referring to David Miller, the W.M. Keck Foundation Professor of Electrical Engineering. “Up to 80 percent of the microprocessor power is consumed by sending data over the wires – so-called interconnects.”

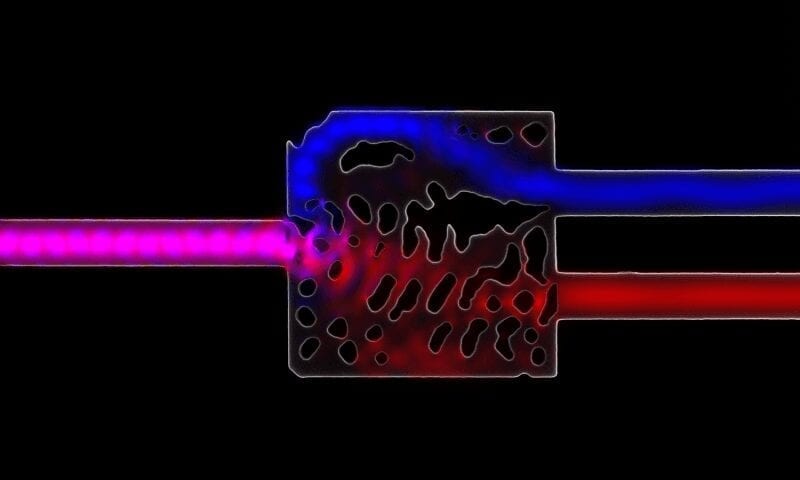

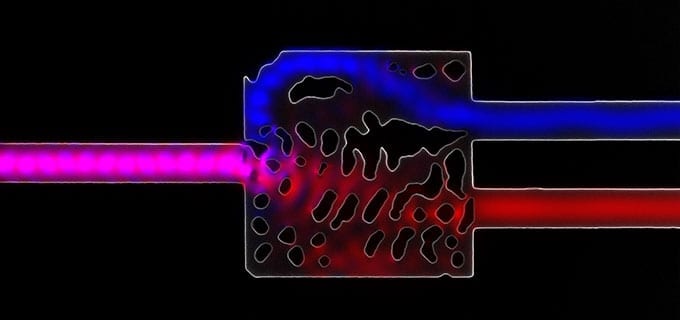

In a Nature Photonics article whose lead author is Stanford graduate student Alexander Piggott, Vuckovic, a professor of electrical engineering, and her team explain a process that could revolutionize computing by making it practical to use light instead of electricity to carry data inside computers.

PROVEN TECHNOLOGY

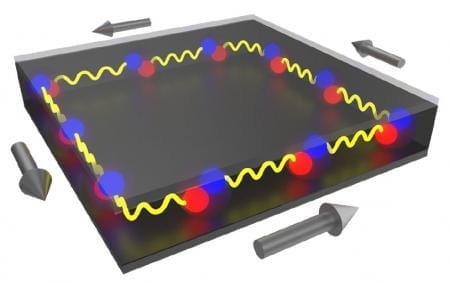

In essence, the Stanford engineers want to miniaturize the proven technology of the Internet, which moves data by beaming photons of light through fiber optic threads.

“Optical transport uses far less energy than sending electrons through wires,” Piggott said. “For chip-scale links, light can carry more than 20 times as much data.”

Theoretically, this is doable because silicon is transparent to infrared light – the way glass is transparent to visible light. So wires could be replaced by optical interconnects: silicon structures designed to carry infrared light.

But so far, engineers have had to design optical interconnects one at a time. Given that thousands of such linkages are needed for each electronic system, optical data transport has remained impractical.

Now the Stanford engineers believe they’ve broken that bottleneck by inventing what they call an inverse design algorithm.

It works as the name suggests: the engineers specify what they want the optical circuit to do, and the software provides the details of how to fabricate a silicon structure to perform the task.

“We used the algorithm to design a working optical circuit and made several copies in our lab,” Vuckovic said.

In addition to Piggott, the research team included former graduate student Jesse Lu (now at Google,) graduate student Jan Petykiewicz and postdoctoral scholars Thomas Babinec and Konstantinos Lagoudakis. As they reported in Nature Photonics, the devices functioned flawlessly despite tiny imperfections.

“Our manufacturing processes are not nearly as precise as those at commercial fabrication plants,” Piggott said. “The fact that we could build devices this robust on our equipment tells us that this technology will be easy to mass-produce at state-of-the-art facilities.”

The researchers envision many other potential applications for their inverse design algorithm, including high bandwidth optical communications, compact microscopy systems and ultra-secure quantum communications.

Read more: STANFORD ENGINEERS’ BREAKTHROUGH HERALDS SUPER-EFFICIENT LIGHT-BASED COMPUTERS

The Latest on: Light-Based Computers

[google_news title=”” keyword=”Light-Based Computers” num_posts=”10″ blurb_length=”0″ show_thumb=”left”]

via Google News

The Latest on: Light-Based Computers

- What's Going on Here: Not Seeing the Lighton May 9, 2024 at 3:59 am

I assumed the inquiry sign would light up about the same time the final horse reached ... Now, the thousands in attendance and millions watching on television, computers, and mobile devices know you ...

- Marvel’s making an ‘interactive story’ based on the What If...? show for Apple Vision Proon May 8, 2024 at 11:39 am

Marvel and Industrial Light & Magic have teamed up to make a mixed-reality interactive story for the Apple Vision Pro. This content will be based on the show What If…?

- IGI Launches New Light Performance Reportson May 6, 2024 at 8:44 pm

IGI has introduced Light Performance Grading Reports showcasing round brilliant cut diamonds with exceptional optical qualities.

- Scientists could make blazing-fast 6G using curving light rayson May 6, 2024 at 5:30 am

co-author of the study and professor of electrical and computer engineering at Rice University, in a statement. Related: Scientists create light-based semiconductor chip that will pave the way for 6G ...

- A science-based afterlife: Can quantum entanglement save my failing body? - opinionon May 4, 2024 at 3:13 am

Will quantum biology finally provide a fact-based explanation reconciling the supernatural with the physical world?

- Fundamental Issues In Computer Vision Still Unresolvedon May 1, 2024 at 5:00 pm

The change from lab projects to everyday uses came as researchers switched from rules-based systems that simulated visual processing as a series of if/then statements (if red and round, then apple) to ...

- Animations of light and abstract ideas feature SU’s computer art programon April 30, 2024 at 5:49 pm

Sarah Golrokh, a first-year graduate student in the computer arts program, also created an animated video for the exhibit. Titled after the Buddhist and Hinduist term “Samsara,” her 2D animation ...

- The $1 Billion Bet on Quantum Computers That Process Lighton April 30, 2024 at 12:30 pm

Founded in 2016, PsiQuantum hit the headlines in 2021 when it raised $700 million to pursue its goal of building useful quantum computers within a decade. This week, it announced a similar injection ...

- Could fungal computers help ease workplace stress?on April 30, 2024 at 7:16 am

Emerging technology might help alleviate workplace stress – but only as part of a broader package that looks at the big picture ...

- BREAKTHROUGH : Lightsolver Makes Ultrafast Laser Based Computerson April 27, 2024 at 5:00 pm

LightSolver, creator of a new laser-based computing paradigm ... LightSolver calls its technology quantum-inspired because it mimics some aspects of quantum computers, such as scanning all ...

via Bing News