A SET of straight and gleaming teeth makes for a beautiful smile. But how many people who have undergone a little dental maintenance know that they may have inside their mouths some of the first products of a new industrial revolution? Tens of millions of dental crowns, bridges and orthodontic braces have now been produced with the help of additive manufacturing, popularly known as 3D printing. Forget the idea of hobbyists printing off small plastic trinkets at home. Industrial 3D printers, which can cost up to $1m, are changing manufacturing.

The business of dentures shows how. For the metal bits in false teeth, dentists have long relied upon a process called “investment casting”. This involves creating an individual model of a person’s tooth, often in wax, enclosing it in a ceramic casing, melting out the wax and then pouring molten metal into the cavity left behind. When the cast is split open, the new metal tooth is removed. It is fiddly, labour-intensive and not always accurate; then again the casting method is some 5,000 years old.

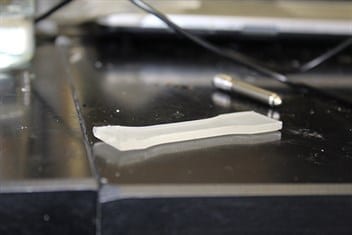

Things are done differently at an industrial unit in Miskin, near Cardiff, set up by Renishaw, a British engineering company. The plant is equipped with three of the firm’s 3D printers; more will be added soon. Each machine produces a batch of more than 200 dental crowns and bridges from digital scans of patients’ teeth. The machines use a laser to steadily melt successive layers of a cobalt-chrome alloy powder into the required shapes. The process is a bit like watching paint dry—it can take eight to ten hours—but the printers run unattended and make each individual tooth to a design that is unique to every patient. Once complete, the parts are shipped to dental laboratories all over Europe where craftsmen add a layer of porcelain. Some researchers are now working on 3D printing the porcelain, too.

Say “ah”

The mouth is not the only bodily testing-ground for 3D-printed products. Figures gleaned by Tim Caffrey of Wohlers Associates, an American consultancy that tracks additive manufacturing, show that more than 60m custom-shaped hearing-aid shells and earmoulds have been made with 3D printers since 2000. Hundreds of thousands of people have been fitted with 3D-printed orthopaedic implants, from hip-replacement joints to titanium jawbones, as well as various prosthetics. An untold number have benefited from more accurate surgery carried out using 3D-printed surgical guides; around 100,000 knee replacements are now performed this way every year.

That the health-care industry has so swiftly adopted additive manufacturing should be no surprise. People come in all shapes and sizes, so the ability of a 3D printer to offer customised production is a boon. The machines run on computer-aided design (CAD) software, which instructs a printer to build up objects from successive layers of material; a medical scan in effect functions as your CAD file. And software is faster and cheaper to change than tools used in a traditional factory, which is designed to churn out identical products.

Learn more: Additive manufacturing: A printed smile

The Latest on: Additive manufacturing

[google_news title=”” keyword=”Additive manufacturing” num_posts=”10″ blurb_length=”0″ show_thumb=”left”]

via Google News

The Latest on: Additive manufacturing

- Fonon Corporation Highlights Applications for Its Laser Cutting Technology in Agricultural Equipment Manufacturingon May 3, 2024 at 12:45 pm

Fonon Corporation, a multi-market holding company, R&D center, equipment designer and manufacturer of advanced laser material processing systems for subtractive and additive manufacturing, highlights ...

- AddUp launches LevelUp to support all stages of Additive Manufacturing processon May 3, 2024 at 5:41 am

AddUp has announced the establishment of a new Service Department to provide a range of support from hardware to design and qualification.

- US Air Force employs Phase3D to develop real-time Additive Manufacturing inspectionon May 3, 2024 at 5:38 am

Phase3D has been selected by the US Air Force to further Additive Manufacturing quality inspection through a Phase I contract.

- Transforming the battlefield: How DARPA’s manufacturing innovations is fuelling military flexibilityon May 3, 2024 at 12:53 am

DARPA has been attempting to revolutionise military logistics with innovative manufacturing programmes like SURGE. Such programmes have been aimed at streamlining the qualification process and ...

- GE Additive rebrands as Colibrium Additiveon May 2, 2024 at 11:01 pm

As part of the Colibrium Additive brand transition, the Concept Laser and Arcam EBM legacy brands will be retired. Originally, the names of the two companies acquired by GE in November 2016 to form GE ...

- The Characterization of Additive Manufacturing Powderson May 2, 2024 at 4:08 am

This article discusses the chemistry of additive manufacturing (AM) powders and the chemical analysis of raw ingredients, recycled materials, and feedstocks. To physically characterize these powders, ...

- Understanding Additive Manufacturing Processeson May 2, 2024 at 4:08 am

This article presents a basic overview of how additive manufacturing (AM) processes work, offering context for material characterization requirements by highlighting the main features of the ...

- State issues $600,000 in grants for additive manufacturing technologyon May 1, 2024 at 7:56 am

Governor Ned Lamont announced on the morning of May 1 that Connecticut is providing six businesses with $100,000 grants to ...

- Phase3D awarded Phase US AFRL contract to advance additive manufacturing quality inspectionon May 1, 2024 at 1:33 am

Phase3D has been awarded a Phase 1 contract by the US Air Force Research Lab (AFRL) that will see it conduct further research into additive manufacturing quality inspection.

- SPEE3D PARTNERS WITH NEW JERSEY INNOVATION INSTITUTE (NJII) TO BRING COLD SPRAY ADDITIVE MANUFACTURING TECHNOLOGY TO STUDENTS AND MILITARYon April 30, 2024 at 2:00 am

Newark, New Jersey, April 30, 2024 (GLOBE NEWSWIRE) -- SPEE3D, a leading metal additive manufacturing company, announced they are working with New Jersey Innovation Institute (NJII) to bring Cold ...

via Bing News