Networking: Emerging undersea data networks are connecting submarines, aquatic drones and other denizens of the deep

DURING the Cuban missile crisis of October 1962 the Soviet Union stationed submarines in the region in order to be able to sink American ships in the event of war. But communication between the submarines and Soviet high command was hard. Electrically conductive salt water absorbs radio waves, so exchanging information with Moscow required the submarines to ascend to periscope depth in waters patrolled by American planes and ships. Between scheduled transmissions Soviet crews also poked antennae out of the water and listened to commercial radio to see if hostilities had broken out. A blunder could have been catastrophic, says Alexandre Sheldon-Duplaix, a naval-warfare historian at France’s defence ministry, because the Soviet submarines were armed with nuclear torpedoes that the West did not even know existed.

In the decades that followed navies continued to be dogged by the difficulty of establishing underwater data links. In the 1980s America decided not to integrate its new “Los Angeles” class of attack submarines with aircraft-carrier groups, says Norman Friedman, a former consultant to the secretary of the US Navy, because it was concerned that flaky communications links between ships and submarines might lead to collisions or friendly fire. A former commander of an American carrier in the 1990s says he was unable to establish submarine contact “more times than I can even remember”. But now better underwater-communications technologies are changing the rules.

Although traditionally more a “sneaky sniper” than a team player, as Eric Wertheim, an American naval analyst, puts it, submarines are increasingly expected to co-ordinate with surface and land forces. Subsea networks being developed by America and its allies will shuffle data between submarines, aquatic drones and sensors via devices that sway beneath the water or bob on its surface. They will make it possible to detect enemy vessels and mines and allow submarines to link up with surface ships, aircraft and distant command centres, says Vernon Clark, America’s former chief of naval operations. Undersea networks could also monitor waterways and gather scientific data.

Making waves

In the 1970s and 1980s both America and the Soviet Union built underwater-signalling systems based on “extremely low frequency” (ELF) radio waves. Both systems needed large electrodes, buried in the ground 50-60km apart, and could then send signals to submarines thousands of kilometres away—but only one way, and at a rate of around ten characters per minute. To overcome these limitations, more recent research has focused on signalling using sound, over shorter ranges.

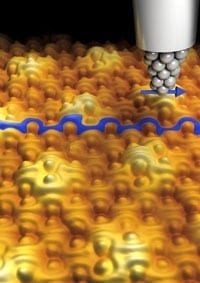

The big technical challenges have been mostly overcome, says John Potter of NATO’s Centre for Maritime Research and Experimentation (CMRE) in La Spezia, Italy, who heads one of several groups building underwater networks based on small devices called acoustic nodes. These could be “shovelled out of a plane”, says Mr Potter, to provide the military alliance with an unprecedented ability to gather intelligence, communicate and co-ordinate its forces underwater. Akin to mobile-phone towers but communicating using pulses of sound rather than radio waves, the nodes are placed a kilometre or so apart. A few extra nodes are needed because acoustic signals can be scrambled or lost near a choppy surface, in fast currents or in a region with a sharp temperature change.

Each node, which costs $5,000-10,000, is around the size of a canister of tennis balls. It contains a computer to process signals, a microphone to pick up sound waves, and a piezoelectric transducer to emit them. This transducer, similar in size to a small plate, is made of a special material that expands and contracts suddenly when a voltage is applied, creating an acoustic wave in the water. This signal is picked up by other nearby nodes, which retransmit it as appropriate to more distant ones, like an underwater internet.

Seaweb, an underwater network being designed at the Naval Postgraduate School in Monterey, California, and the Space and Naval Warfare Systems Command in San Diego, takes a similar approach. Its nodes have been tested under the Arctic ice sheet and in water 300 metres deep. Data packets hop from one node to another until they reach their destination—a submarine, a subsea drone, a warship or a “gateway” node at the surface. Gateway nodes use a satellite-radio link to connect the underwater network to the rest of the world.

The Latest Bing News on:

Undersea data networks

- HII delivers Virginia class submarine USS New Jersey to Navyon April 25, 2024 at 7:47 am

According to a PR published by HII on April 25, 2024, the company confirmed that its Newport News Shipbuilding division has officially handed over the Virginia-class fast-attack submarine, named New ...

- Intelligent Systems Employed in Constructing China’s Deepest Undersea Tunnelon April 25, 2024 at 3:12 am

and big data analysis. The intelligent tunneling system, a core component of the tunnel boring, incorporates advanced technologies like neural networks, machine learning, predictive algorithms, edge ...

- Confluence Networks, Laser Light Ink $20M Deal for Undersea Fiber Opticson April 23, 2024 at 11:06 pm

Confluence Networks, a developer and provider of subsea fiber-optic network connectivity, and Laser Light Communications, a developer and provider of software-controlled optical network services, ...

- Study: SEA retail media network ad spend to hit US$4.7 billion by 2030on April 23, 2024 at 5:06 pm

SEA have already incorporated retail media into their media plans while 99% of brands in SEA plan to invest more advertising dollars in RMNs.

- Submarine Cable Market Projected to Grow at 5% CAGR, Surpassing US$ 3,970 Million by 2034on April 18, 2024 at 7:25 pm

The submarine cable market is poised for remarkable growth, projected to surge to an impressive US$ 3,970 Million by the year 2034, boasting a steady 5% CAGR. This surge underscores the increasing ...

- 2024 West Africa Submarine Cable Outage Reporton April 17, 2024 at 5:00 pm

DINX/ZANOG Content Delivery Network (CDN) caching saves local Durban ISPs ... Internet services in Africa will also help mitigate the impact of submarine cable cuts. Recent growth in data center ...

- Nearly $1B In Munitions Fired In Red Sea, Mediterranean, U.S. Navy Chief Sayson April 16, 2024 at 6:22 pm

Nearly $1B In Munitions Fired In Red Sea, Mediterranean, U.S. Navy Chief Says is published in Aerospace Daily & Defense Report, an Aviation Week Intelligence Network (AWIN) Market Briefing and is ...

- NATO commander warns critical undersea cables and pipes 'under threat' from Russia and other foeson April 16, 2024 at 11:31 am

Deep sea cables and pipelines that are at risk of attack pose a security challenge for NATO countries.

- Hidden threat: Global underground infrastructure vulnerable to sea-level riseon April 15, 2024 at 2:11 pm

As sea levels rise, coastal groundwater is lifted closer to the ground surface while also becoming saltier and more corrosive. A recent study by Earth scientists at the University of Hawai'i (UH) at ...

- Data from random days doesn't teach us about sea ice or global warming | Fact checkon April 15, 2024 at 2:01 pm

Antarctic sea ice has not yet exhibited a statistically significant overall decline, though an array of evidence shows Earth is warming.

The Latest Google Headlines on:

Undersea data networks

[google_news title=”” keyword=”undersea data networks” num_posts=”10″ blurb_length=”0″ show_thumb=”left”]

The Latest Bing News on:

Underwater network

- How Underwater Telecom Cables Could Help Detect Tsunamison April 26, 2024 at 1:03 pm

Scientists are adding sensors to an underwater cable network to monitor changes in the ocean and quickly detect earthquakes and tsunamis.

- Dubai underwater: Climate change amplified historic rainson April 25, 2024 at 2:07 pm

The torrential rains that killed 24 people in the UAE and Oman on April 15 and 16 were 10% to 40% more intense as a result of climate change, according to a World Weather Attribution study.

- Honoring Don’t Trash Our Treasure’s 2024 Most Treasured Citizenson April 24, 2024 at 7:00 pm

“It’s a sign of hope,” Foord said as he marveled at the health of the corals he saw on the dive. “I think that the corals living on these reefs could be the future parents of the resilient corals of ...

- Bumblebee Species Able To Survive Underwater for Up to a Weekon April 24, 2024 at 10:00 am

PICKS are stories from many sources, selected by our editors or recommended by our readers because they are important, surprising, troubling, enlightening, inspiring, or amusing. They appear on our ...

- Here’s who really benefits from Biden’s $153 billion in student-debt cancellationon April 23, 2024 at 2:59 am

If we canceled more student debt, we would get more student borrowers able to make those kinds of investments.” Little data on the impact of student-debt cancellation Over the past several years, ...

- Video: Louise Thompson goes underwater for first time in months after stoma bag fittedon April 21, 2024 at 10:08 pm

Look how happy she is back in the water.

- Underwater drones to be tested in Japan with aims to promote domestic manufacturingon April 17, 2024 at 8:32 pm

Japan expects AUVs to be used for inspecting offshore wind power generation facilities and underwater surveillance. Read more at straitstimes.com.

- Taiwan's Air Force Plunges Into Underwater Survival Trainingon April 17, 2024 at 7:48 am

Under strobing lights, a vessel carrying Taiwanese air force lieutenants plunged into an indoor pool with roiling water on Wednesday -- simulating adverse weather conditions to train military ...

- Some bumblebees can survive underwater for up to a week, new study showson April 16, 2024 at 5:01 pm

(CNN) — An experimental error led a team of scientists researching bumblebees to make a startling discovery: the insects’ remarkable ability to survive underwater ...

- EU pledges 3.5 billion euros to protect the oceanon April 16, 2024 at 8:54 am

The European Union will spend 3.5 billion euros ($3.71 billion) to protect the ocean and promote sustainability through a series of initiatives this year, the EU's top environment official said on ...

The Latest Google Headlines on:

Underwater network

[google_news title=”” keyword=”underwater network” num_posts=”10″ blurb_length=”0″ show_thumb=”left”]