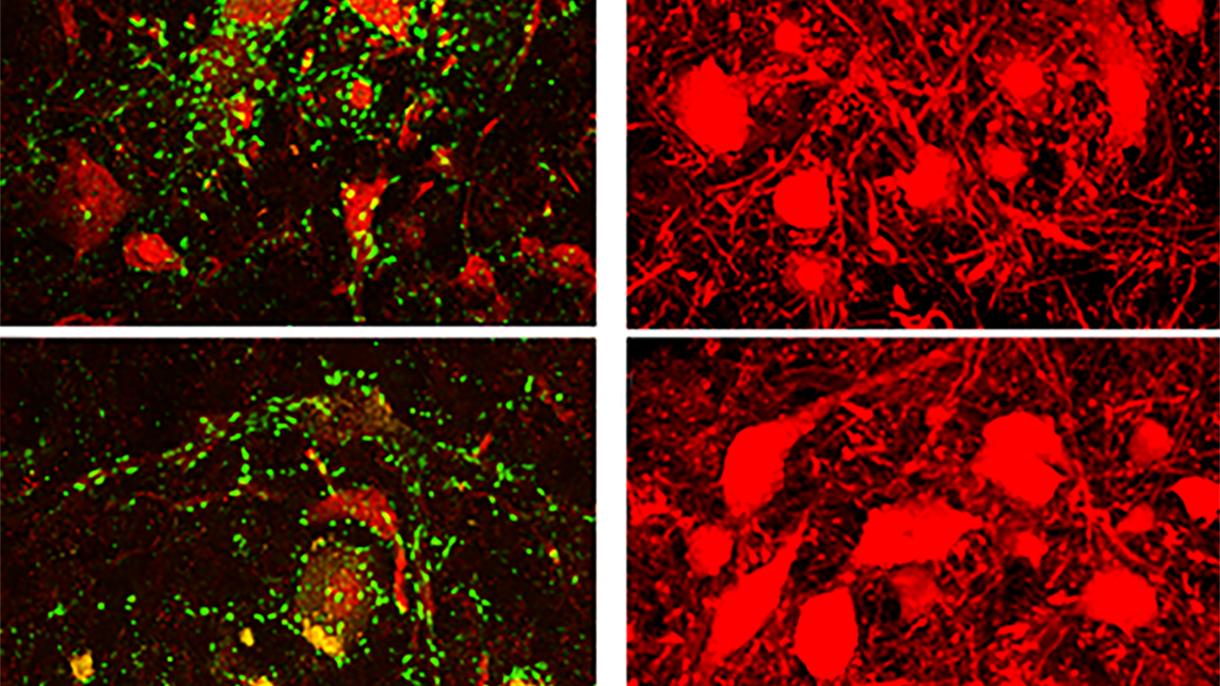

These images, adapted from the research paper, show that motor neurons in the spinal cord of an aged mouse (bottom) have fewer synaptic inputs than those in younger adults (top).

A new study led by researchers at Brown University’s Carney Institute for Brain Science offers a blueprint to help scientists prevent and reverse motor deficits that occur in old age.

As humans age, tasks that require coordinated motor skills, such as navigating stairs or writing a letter, become increasingly difficult to perform. Reduced mobility caused by aging is strongly associated with adverse health outcomes and a diminished quality of life.

Researchers at Brown led by Gregorio Valdez, an associate professor of molecular biology, cell biology and biochemistry, discovered that the loss of connectivity of motor neurons in the spinal cord — not the death of those neurons, as was previously thought — is what impairs voluntary movements during aging.

“This is an important fundamental discovery because it tells us that treatments are possible to prevent and reverse motor deficits that occur as we age,” said Valdez, who is affiliated with both the Center for Translational Neuroscience and the Center for Alzheimer’s Disease Research at the Carney Institute and Brown’s Center on the Biology of Aging. “The primary hardware, motor neurons, are spared by aging. If we can figure out how to keep synapses from degenerating, or mimic their actions using pharmacological interventions, we may be able to treat motor issues in the elderly that often lead to injuries due to falls.”

For the study, published on Wednesday, May 10, in the Journal of Clinical Investigation Insight, researchers examined spinal motor neurons in three species, including humans, rhesus monkeys and mice.

“These findings revealed that, as individuals age, motor neurons lose many of the connections that direct their function,” said Ryan Castro, first author of the study, who earned a Ph.D. in neuroscience from Brown in 2022.

Spinal motor neurons connect the central nervous system with skeletal muscles. The neurons receive and relay signals at synapses to activate the muscles needed to perform a specific movement. Because of their critical function, Valdez said, the loss of either motor neurons or their synapses would impair voluntary movements.

The number and size of motor neurons do not significantly change during aging, the researchers discovered. However, they undergo other processes that contribute to aging.

“Aging causes motor neurons to engage in self-destructive behavior,” Valdez said. “While motor neurons do not die in old age, they progressively increase expression of molecules that cause degeneration of their own synapses and cause glial cells to attack neurons, and that increases inflammation.”

Some of these aging-related genes and pathways are also found altered in motor neurons affected with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS).

The researchers now plan to pursue studies to target molecular mechanisms they found altered in motor neurons that could be responsible for the loss of their own synapses with advancing age.

Original Article: Old motor neurons don’t die, scientists discover — they just slow down

More from: Brown University | Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University

The Latest Updates from Bing News

Go deeper with Bing News on:

Age-related motor deficits

- Biden’s Numbers, April 2024 Update

The trade deficit for goods and services is about 18.8% higher ... Labor Force Participation — The labor force participation rate (the percentage of the total population over age 16 that is either ...

- What are the core ADHD symptoms?

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a neurodevelopmental condition. It affects the way the brain functions. Symptoms exist on a spectrum of severity ranging from mild to severe and ...

- New Jersey’s 3 Cheapest Grocery Stores, You Might Be Surprised

There are so many different grocery stores to choose from in New Jersey. But, I know you have your one favorite you probably always go to.

- Dr. Reddy’s issues voluntary recall of drug to treat rare metabolism disorder in United States

Dr. Reddy’s Laboratories Inc. has not received any reports of adverse events related to this recall to date, it stated.

- Autism Checklist: How to Prepare for Your First Diagnostic Evaluation

1,2 While an experienced clinician can reliably identify ASD in children as young as age 2 years, many children do not receive ... using the appropriate diagnostic criteria. A. Persistent deficits in ...

Go deeper with Bing News on:

Motor neurons

- Brainless memory makes the spinal cord smarter than previously thought

Researchers have discovered the neural circuitry in the spinal cord that allows brain-independent motor learning. The study found two critical groups of spinal cord neurons, one necessary for new ...

- Coronation Street star Peter Ash explains Paul's blunder in radio storyline

Coronation Street star Peter Ash has explained Paul Foreman 's big blunder in his radio storyline. Scenes airing next week will see Paul appear on Amy Barlow's new student radio show as one of her ...

- Coya Therapeutics Presents Updated ALS Biomarker Data at the 2nd Annual Johnson Center Symposium

Coya Therapeutics, Inc. (Nasdaq: COYA) (“Coya” or the “Company”), a clinical-stage biotechnology company developing biologics intended to enhance regulatory T cell (Treg) function, announces that Dr.

- Differentiating cerebral cortical neurons to decipher molecular mechanisms of neurodegeneration

A research team led by Professor Haruhisa Inoue (Department of Cell Growth and Differentiation) derived iPS cells (iPSC) from α-synucleinopathy patients with early-onset familial Parkinson's disease ...

- Late Charlie Bird's documentary "Ransom '79" hits Irish cinemas in May

Veteran investigative journalist and Mother Neurone Disease advocate passed away in March this year. Now his final story, the documentary "Ransom '79" is being released in Irish cinemas on May 24.