A recent article on Kaiser Health News reported on a new drug for the treatment of hepatitis C for which the manufacturer charges $1,000 a pill, or $84,000 for a 12-week course of treatment.

Chronic hepatitis C is a leading cause of serious liver disease, including cancer.

It has been estimated that providing the drug to all patients known to have hepatitis C would substantially drive up budgets for public insurance programs and premiums for private insurance, though over the longer run there would be offsets to these upfront costs by obviating the need for alternative treatments, including liver transplants (see Pages 69-71 of the meeting summary from the California Technology Assessment Forum, linked to above).

The high price charged for the drug has led to street protests in San Francisco and calls for congressional hearings. It also provoked from The New York Times a stern editorial, “How Much Should Hepatitis C Treatment Cost?”

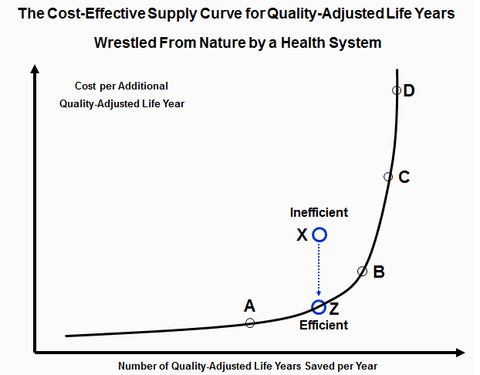

These reports brought to mind my post in November 2012. In that, I presented the above heuristic visual.

The horizontal line in this graph represents additional quality-adjusted life years (widely known in the research community as QALYs) wrestled from nature by a nation’s health system, arrayed in the increasing incremental costs per QALY gained. The vertical axis represents the incremental cost per additional QALY the health care system bestows on some patient.

I had called the solid line in the graph the QALY supply curve that the nation’s health system presents to society – the health system’s “offer curve,” in commercial parlance. A point on the line (e.g., Z) represents the most cost-effective (lowest cost) treatment capable of yielding the associated QALY. The treatment represented by point X would not be an efficient way to gain that QALY, because treatment Z is more cost-effective.

With this offer curve, a health system confronts the rest of the nation with two morally challenging questions:

1. Is there a maximum price above which society no longer wishes to purchase added QALYs from its health system, even with the most cost-effective treatments (e.g., Point C)?

2. Should that maximum price be the same for everyone, or could there be differentials – for example, a lower maximum price for patients covered by taxpayer-financed health programs (e.g., Medicaid, Tricare, the Veterans Administration health system and perhaps Medicare), a wide range of higher prices for premium-financed commercial insurance, depending on the generosity of the benefit package that the premium covers, and yet higher prices for wealthy people able to pay out of their own resources very high prices to purchases added QALYs for the family?

I tell my students that their parents and grandparents in the United States have always avoided confronting these morally taxing questions. They simply paid whatever was charged for whatever new medical technology came down the pike, letting per-capita health care spending grow annually at a long-term growth rate 2 to 2.5 percentage points above the growth in per-capita gross domestic product. The result has been spending far above the level of spending one observes in any other industrialized society (although we may implicitly have imposed a maximum price on QALYs for some Americans without health insurance).

But I also tell my students that they most likely will not be able to kick that particular can down the road much farther.

The Latest on: Quality-adjusted life years

[google_news title=”” keyword=”Quality-adjusted life years” num_posts=”10″ blurb_length=”0″ show_thumb=”left”]

via Google News

The Latest on: Quality-adjusted life years

- Women may live longer but they have poorer quality lives than men, new study findson May 4, 2024 at 6:21 am

The investigation showed that men are more likely to be involved in a car crash while women tend to suffer more from anxiety and depression.

- How gender shapes health: Women live longer but with poorer quality of lifeon May 3, 2024 at 11:15 am

Men experience a greater degree of health loss and have a higher burden of diseases that lead to premature death, but women suffer more pathologies such as lower back pain, depression, and anxiety, ac ...

- Quality of Life and Economic Costs Associated With Postthrombotic Syndromeon April 15, 2024 at 5:00 pm

OR ('quality adjusted life years'/exp OR 'quality adjusted life years':ti,ab) OR 'adjusted life years' OR 'years of life lost':ti,ab OR cost:ti,ab OR costs:ti,ab OR economic:ti,ab OR economics ...

- Can Ozempic be a breakthrough drug and overpriced at the same time?on April 3, 2024 at 6:06 am

Last month, Medicare announced that it will cover the new class of anti-obesity drugs, including Wegovy and Ozempic, for patients at risk of stroke or heart attack. It’s a watershed moment for a ...

- Cost–Utility Analysis of Nanoparticle Albumin-Bound Paclitaxel versus Paclitaxel in Monotherapy in Pretreated Metastatic Breast Cancer in Spainon March 23, 2024 at 5:00 pm

Aim: The COSTABRAX study evaluated the cost–effectiveness of nanoparticle albumin-bound paclitaxel (nab-paclitaxel) versus polyethylated castor oil-based standard paclitaxel (sb-paclitaxel) in ...

- Top 20 happiest countries in the world in 2024on March 20, 2024 at 9:19 am

Starting in 2021, the World Happiness Report has argued for using WELLBYs (Well-Being-Adjusted Life-Years) as a superior measure. Quality-Adjusted Life Years (QALYs) primarily measure an ...

- House Of Representatives Passes Bill To Ban Use Of QALYs In Federally Funded Healthcare Programson February 9, 2024 at 12:07 pm

The bill would prohibit federally-funded healthcare programs from using the Quality Adjusted Life Year to determine pricing and reimbursement of healthcare services and technologies, including ...

- An investigation into methods for demonstrating when a generic, preference-based measure of health-related quality of life misrepresents health gainon August 3, 2023 at 11:16 am

NICE uses cost effectiveness analysis to inform guidance, with Quality Adjusted Life Years (QALYs) as the measure of benefit. For the sake of consistency, NICE prefers that EQ-5D-3L is used for the ...

- Congress Should Ban Quality-of-Life Health-Care Rationingon June 27, 2023 at 6:22 am

Thomas Massie Maintains Speaker Johnson Has a Short Shelf Life More Abortions, More Taxpayer Dollars, and Fewer Health Services Auto Ban: German Minister Threatens the End of Weekend Driving Uri ...

- Specific Issues Reports for H.R.485 by GSK plc, 118th Congresson May 8, 2023 at 11:42 am

from using prices that are based on quality-adjusted life years (i.e., measures that discount the value of a life based on disability) to determine relevant thresholds for coverage, reimbursements, or ...

via Bing News