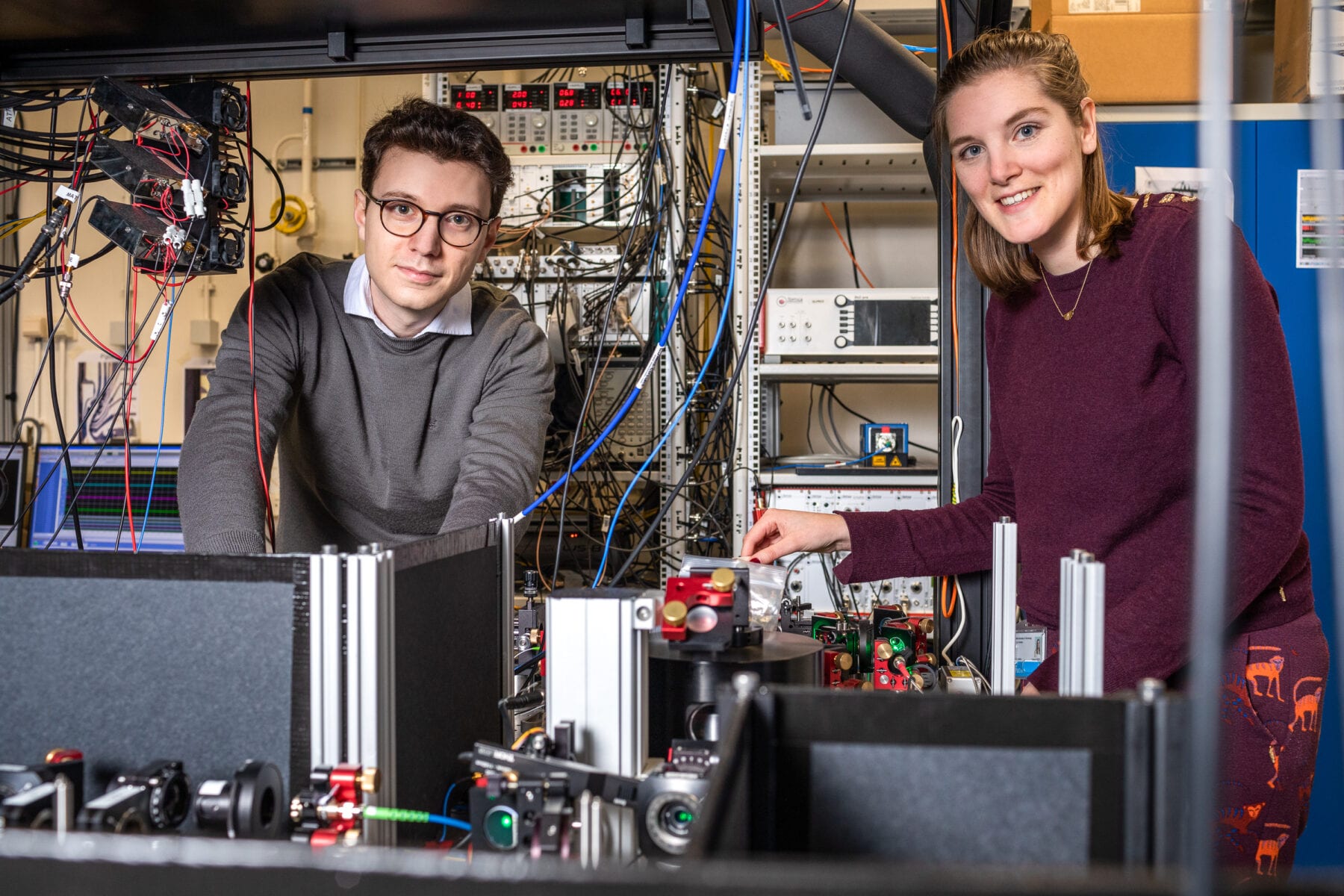

Christine Picard, Ph.D., collects blow flies to study changes in animal ecosystems.

They say you are what you eat; that’s the case for every living thing, whether it’s humans, animals, insects, or plants, thanks to stable isotopes found within.

Now a new study explores these stable isotopes in blow flies as a non-invasive way to monitor the environment through changes in animals in the ecosystem. The work by IUPUI researchers Christine Picard, William Gilhooly III, and Charity Owings, was published April 14 in PLOS ONE.

A postdoctoral researcher at the University of Tennessee-Knoxville, Owings was a Ph.D. student at IUPUI at the time of the study.

“Blow flies are found on all continents, with the exception of Antarctica. Therefore, blow flies are effectively sentinels of animal response to climate change in almost any location in the world,” said Gilhooly, who said the disruptions of climate change has increased the need to find new ways to monitor animals’ environments without disturbing them.

The multidisciplinary research between the biology and earth science departments began more than four years ago to answer a fundamental ecological question: “What are they (blow flies) eating in the wild,” Owings asked. “We know these types of flies feed on dead animals, but until now, we really had no way of actually determining the types of carcasses they were utilizing without actually finding the carcasses themselves.”

“Stable isotopes are literally the only way we could do that in a meaningful way,” Picard added.

Stable isotopes include carbon, nitrogen, hydrogen, oxygen, among others. Stable isotopes are found in the food we eat, and become a part of us.

“When we eat a hamburger, we are getting the carbon isotopes that came from the corn that the cow was fed. Flies do the exact same thing,” said Gilhooly.

Picard and Owings set out to collect blow flies in Indianapolis, Yellowstone National Park and the Great Smoky Mountains.

“Collecting flies is easy: have rotten meat, can travel,” said Picard. “That is it, we would go someplace, open up our container of rotten meat, and the flies cannot resist and come flying in. Collections never took longer than 30 minutes, and it was like we were never there.”

Once the flies were collected, they were placed in a high-temperature furnace to convert the nitrogen and carbon in the blow fly into nitrogen gas and carbon dioxide gas. Those gases were then analyzed in a stable isotope ratio mass spectrometer, which shows slight differences in mass to reveal the original isotope composition of the sample.

“Nitrogen and carbon isotopes hold valuable information about diet. Animals that eat meat have high nitrogen isotope values, whereas animals that eat mainly plants have low nitrogen isotope values,” said Gilhooly. “Carbon isotopes will tell us the main form of sugar that is in a diet. Food from an American diet has a distinct isotope signature because it has a lot of corn in it, either from the corn fed to domesticated animals or high fructose corn syrup used to make most processed foods and drinks. This signal is different from the carbon isotopes of trees and other plants. These isotope patterns are recorded in the fly as they randomly sample animals in the environment.”

Identifying the stable isotopes allowed the researchers to determine if the blow flies were feeding on carnivores or herbivores when they were larvae.

“With repeated sampling, one can keep an eye on animal health and wellness,” said Picard. “If the flies indicate a sudden, massive increase in dead herbivores –and knowing what we know right now that typically the herbivores are readily scavenged and not available for flies, that could tell us one of two things: herbivores are dying yet the scavengers don’t want anything to do with them as they may be diseased, or there are more herbivores than the carnivores/scavengers, and perhaps the populations of these animals has decreased.”

In Indianapolis, the majority of the blow fly larvae feed on carnivores. The researchers speculate this is because of the large number of animals being hit and killed by cars, making carcass scavenging less likely and more available to the blow flies to lay their eggs.

However, they were surprised by their findings in the national park sampling sites, where the larvae fed on carnivores instead of the herbivores, despite the herbivores’ greater numbers. They speculate the competition is higher to scavenge for the larger herbivore carcasses and not readily accessible for the blow flies.

In addition, Picard, Gilhooly and Owings observed the impact of humans on animals. The carbon isotopes from the flies found the presence of corn-based foods in Indianapolis, which was expected, but also in the Great Smoky Mountains. With the Smokies being the most visited park in the country, opportunistic scavengers have greater access to human food.

This wealth of information provided by the blow flies will be fundamental to detecting changes within the ecosystem,” said Picard.

Original Article: Blow flies may be the answer to monitoring environment in a non-invasive manner

More from: Indiana University–Purdue University Indianapolis

The Latest Updates from Bing News & Google News

Go deeper with Bing News on:

Blow flies

- VIDEO: Fly disrupts warm-up at MODUS Super Series

Marvin van Velzen and Ray Mulvey had to wait a while before they could start their match in the MODUS Super Series. A fly passed by during their practice darts.

- ‘No excuse’ after Padres blow big lead late, fall to Rockies in Coors Field finale

De Los Santos struck out Rockies No. 2 batter Brenton Doyle to start the seventh before Matsui ended the inning. Matsui got through the seventh before giving up a one-out double to Brendan Rodgers and ...

- Florida fishing: Seas blow up this weekend, but inshore fishing has been excellent

Inshore: Snook fishing has been excellent around docks and seawalls from Sailfish Point to Rocky Point and Sewall's Point and the Ernest Lyons Bridge and Evans Crary Bridge. Anglers are pitching live ...

- Loganair pulls out of Teesside Airport as airline scraps Aberdeen route in 'disappointing' blow

Loganair has pulled out of Teesside Airport as it scraps its route to Aberdeen. The Scottish airline has announced that it will be pulling the flights from May 10 later this year, following a review ...

- Vikings blow out Titans in rivalry match

The Palo Alto High School Vikings boys’ baseball team (10-11) defeated the Henry M. Gunn High School Titans (4-14), 11-3, on Friday at home in a game with high rivalry tensions and implications for ...

Go deeper with Google Headlines on:

Blow flies

[google_news title=”” keyword=”blow flies” num_posts=”5″ blurb_length=”0″ show_thumb=”left”]

Go deeper with Bing News on:

Non-invasive environmental monitoring

- The next frontier of forensic science: blood splatter in microgravity?

Feedback is pleased to see that researchers are looking into the urgent issue of which angle blood might travel at following a violent act in space ...

- ADMT: Advancements in Medical Device Innovation

Reflecting a commitment to environmental sustainability ... ADMT is undergoing a redesign of the company’s patented, non-invasive, FDA-approved medical device, the Aurex-3 ®, used for treating and ...

- Grasses at a Glance blog earns award from national Extension organization

Grasses are a small and often subtle backbone of many ecosystems, making up nearly 30% of the planet’s land cover. They prevent soil erosion, regulate water flow, and provide food and habitat for ...

- New tagging method provides bioadhesive interface for marine sensors on diverse, soft, and fragile species

Tagging marine animals with sensors to track their movements and ocean conditions can provide important environmental and behavioral information. Existing techniques to attach sensors currently ...

- Dutch scientist wins Lee Kuan Yew Water Prize for work on COVID-19 monitoring through wastewater

SINGAPORE: At the height of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, Singapore began testing wastewater to trace the spread of the disease, mirroring efforts by other countries.

Go deeper with Google Headlines on:

Non-invasive environmental monitoring

[google_news title=”” keyword=”non-invasive environmental monitoring” num_posts=”5″ blurb_length=”0″ show_thumb=”left”]