As an ecologist of ice age giants, I long ago came to terms with the fact that I will never look my study organisms in the eye.

I will never observe black-bear-sized beavers through binoculars in their natural habitats, build experimental exclosures to test the effects of mastodons on plants, or even observe a giant ground sloth in a zoo.

As a conservation paleoecologist, I study the natural experiments of the past—like climate change and extinction—to better understand the ecology of a warming, fragmented world. Admitedly, part of the appeal of the ice age past is the challenge of reconstructing long-disappeared landscapes from fragments like pollen, tiny fragments of charcoal, and bits of leaves preserved in lakes. In the absence of mammoths, for example, I rely instead on spores of fungi that once inhabited their dung.

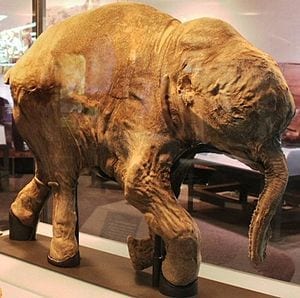

De-extinction could change that. On Friday, a group of geneticists, conservationists, journalists, and others convened in Washington, D.C. to discuss resurrecting extinct species, including the woolly mammoth. De-extinction sounds like science fiction, but it’s rooted in very real conservation concerns. With the sequencing of the woolly mammoth genome complete and recent advancements in biotechnology, the question of whether to clone extinct species like mastodons, dodos, or the Shasta ground sloth is rapidly becoming more of a question of should, rather than how. The latter isn’t straightforward, and involves the integration of a number of cutting edge disciplines, but I’d like to focus on the former: should we clone woolly mammoths?

A growing problem I’ve had (and one which Brian Switek raises in a recent post at National Geographic) is that the de-extinction proposals are Big Ideas, but they they’re often shallow when it comes to ecology. Even the concept of “de-extinction” itself is misleading. Successfully cloning an animal is one thing; rescuing it from the black hole-like pull of extinction is another. Decades of conservation biology research has tried to determine the careful calculus of how many individuals and how much land are needed for a species to survive without major intervention, accounting for its needs for food, habitat, and other resources.

Mammoths have been extinct on continents for over ten thousand years (though dwarf versions survived into the time of the ancient Egyptians on isolated Arctic islands). Even so, the fossil record has yielded rich clues about ecology. All ethical considerations aside, from a conservation biology standpoint, what does it mean to be a mammoth?

The Latest Bing News on:

Cloning Woolly Mammoths

- Science Seeks to Resurrect Woolly Mammoth in Yellowstone by 2028on April 29, 2024 at 8:04 am

That line resonates today, as news broke that a biotech firm called Colossal Biosciences has announced its intentions to bring the Woolly Mammoth back to life and reintroduce it to its pre-historic ...

- What It'll Take to Create 21st-Century Mammoths, Dodos, and Thylacineson April 27, 2024 at 8:16 am

We don’t fully understand how to create an artificial placenta at the moment. We don’t really understand the intricacies of the developmental process. This is all information that we will learn along ...

- woolly mammothon April 25, 2024 at 5:00 pm

Russian scientists say they have a ‘high chance’ of cloning a woolly mammoth Woolly mammoth blood and tissue discovered in Siberia in 2013 will give scientists “a high chance” to clone the ...

- Bringing back the woolly mammoth to roam Earth again. Is it even possible? | The Excerpton April 18, 2024 at 1:45 pm

A company is at the heart of an evolving science that aims to see ancient animals return in the name of preserving and promoting biodiversity.

- What ‘de-extinction’ of woolly mammoths can teach us: a Q&A with evolutionary biologist Beth Shapiroon April 3, 2024 at 5:00 pm

Related: Giant sloths and woolly mammoths ... “I’m going to clone a mammoth.” But in order to clone a mammoth, you need a living cell. You need an intact nuclear genome of a mammoth ...

- Scientists to Clone Woolly Mammoth in Five Yearson March 16, 2024 at 5:20 pm

PCWorld helps you navigate the PC ecosystem to find the products you want and the advice you need to get the job done.

- Reviving the Ice Age - U.S. Scientists Clone Mammoths to Combat Climate Changeon March 12, 2024 at 2:37 am

A world where woolly mammoths are brought back to life through science and technology and trample through nature sounds more like something from "Jurassic Park." Yet a scientific breakthrough ...

- Is the woolly mammoth really on the brink of being resurrected?on March 6, 2024 at 8:02 am

Is it really possible to bring the woolly mammoth back from extinction ... transfer the edited genomes into elephant eggs using the cloning technique used to create Dolly the sheep.

- Woolly Mammoth: The Autopsyon May 21, 2023 at 8:34 pm

Can cloning bring mammoths back from extinction? This documentary follows a team of mammoth specialists and cloning scientists as they dissect the best-preserved mammoth ever found. Advertisement ...

- Of Mammoths and Menon December 27, 2022 at 1:15 am

Ancient hunters killed woolly mammoths for their meat ... soft mammoth tissue in hopes of finding viable cells to clone. (See “Bringing Them Back to Life.”) A few years ago this local boss ...

The Latest Google Headlines on:

Cloning Woolly Mammoths

[google_news title=”” keyword=”Cloning Woolly Mammoths” num_posts=”10″ blurb_length=”0″ show_thumb=”left”] [/vc_column_text]The Latest Bing News on:

De-extinction

- Bees face extinction due to climate change making it too hot to handleon May 3, 2024 at 6:06 am

Bees face extinction because their nests are overheating due to climate change, warns a new study. Wild bumblebees all over the world need a similar nest temperature to thrive. But with global warming ...

- X-MEN '97 Showrunner Beau DeMayo Reveals New Easter Eggs And Answers "Tolerance Is Extinction" Fan Questionson May 2, 2024 at 2:11 am

X-Men '97 Head Writer Beau DeMayo has broken down "Tolerance Is Extinction - Part 1, including easy-to-miss Easter Eggs, the episode's cameos, unanswered questions, and the show's place in the ...

- Congressional Republicans announce resolution to overturn Biden tailpipe ruleon May 1, 2024 at 5:44 pm

Congressional Republicans, led by Sen. Pete Ricketts (R-Neb.) and Rep. John James (R-Mich.), introduced a Congressional Review Act (CRA) resolution Wednesday that would undo the Biden ...

- Rare giant otter arrives at zoo to help save species from extinctionon May 1, 2024 at 6:47 am

A rare male giant otter has arrived at Chester Zoo as part of a conservation breeding program in a bid to help save his species from extinction. The three-year-old named Manú has traveled more than ...

- Study shows climate change and mercury pollution stressed plants for millions of yearson April 30, 2024 at 9:34 am

The link between massive flood basalt volcanism and the end-Triassic (201 million years ago) mass extinction is commonly accepted. However, exactly how volcanism led to the collapse of ecosystems and ...

- Climate change and mercury pollution stressed plants for millions of yearson April 29, 2024 at 5:00 pm

However, exactly how volcanism led to the collapse of ecosystems and the extinction of entire families of organisms ... of Copenhagen), Hamed Sanei (Aarhus University), and Bas van de Schootbrugge ...

- Woolly Mammoths In Yellowstone? Biotech Company Says It Has The Technologyon April 27, 2024 at 8:58 am

Biotech company Colossal Biosciences has announced plans to bring back the extinct woolly mammoth by 2028. They think Yellowstone could be a good place for reintroduction as the environment is ...

- What It'll Take to Create 21st-Century Mammoths, Dodos, and Thylacineson April 27, 2024 at 8:16 am

We don’t fully understand how to create an artificial placenta at the moment. We don’t really understand the intricacies of the developmental process. This is all information that we will learn along ...

- A rare mammal with a trunk-like snout and webbed feet: The Iberian desman faces extinctionon April 24, 2024 at 7:34 am

The ‘Spanish platypus’ is unique to the Iberian Peninsula and a jewel of evolution that has lost up to 70% of the geographical range it occupied three decades ago ...

- How a Cloned Ferret Inspired a DNA Bank for Endangered Specieson April 21, 2024 at 5:00 pm

head of de-extinction efforts at Revive & Restore, a nonprofit outfit that applies biotechnology to conservation. If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism ...

The Latest Google Headlines on:

De-extinction

[google_news title=”” keyword=”de-extinction” num_posts=”10″ blurb_length=”0″ show_thumb=”left”]