Moreover, the new technology has one big benefit.

SOLAR panels get better and cheaper with every passing year. In one way, though, they are still pretty primitive. They work only with light that falls in the visible part of the spectrum. Yet 40% of the solar energy that reaches the Earth is in, or very close to, the infra-red. A cell that could harvest such radiation would be a boon to the solar-power business, but building one has proved difficult. Now, though, as they report in Advanced Materials, a group of researchers led by Michael Strano at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology have figured out how to do it.

When the silicon in a standard solar cell is struck by sunlight, it releases electrons that can be sent off to generate electrical power. Other substances react in the same way to light of other frequencies. Researchers have, for example, known for several years that carbon nanotubes, tiny cylinders of pure carbon, will release electrons when stimulated by infra-red light.

That discovery led to much experimentation, but little progress. The chief difficulty lies in the process used to make the tubes. This actually produces a mixture of two different sorts: ones that have metal-like properties and ones that are semiconducting. Solar cells need the semiconducting variety. Metallic ones poison the process and must be removed before a cell can work properly.

Until now, researchers wishing to do that have been forced to play a tedious game of pick-up-sticks, selecting the semiconducting nanotubes one by one and then sticking them in place with glue. It is possible to make a solar cell this way, but it is time-consuming and expensive. Worse, the chemical instability of the glue means such cells tend to break down rapidly.

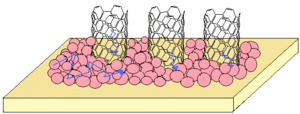

Dr Strano, however, has made use of a new manufacturing process that uses a polymer gel that has an affinity for semiconducting nanotubes, but not metallic ones. He is thus able to extract large amounts of semiconducting tubes from a mixture. That done, he deposits them in a 100 nanometre-thick layer on top of a piece of glass, to which their bulk causes them to stick without the need for glue. The whole thing is then topped with a layer of buckminsterfullerene, a form of carbon in which the atoms are organised as spheres. This conducts away the electricity produced by the nanotubes.

via The Economist

The Latest Streaming News: infra-red solar cell updated minute-by-minute