When UC Berkeley bioengineers say they are holding their hearts in the palms of their hands, they are not talking about emotional vulnerability

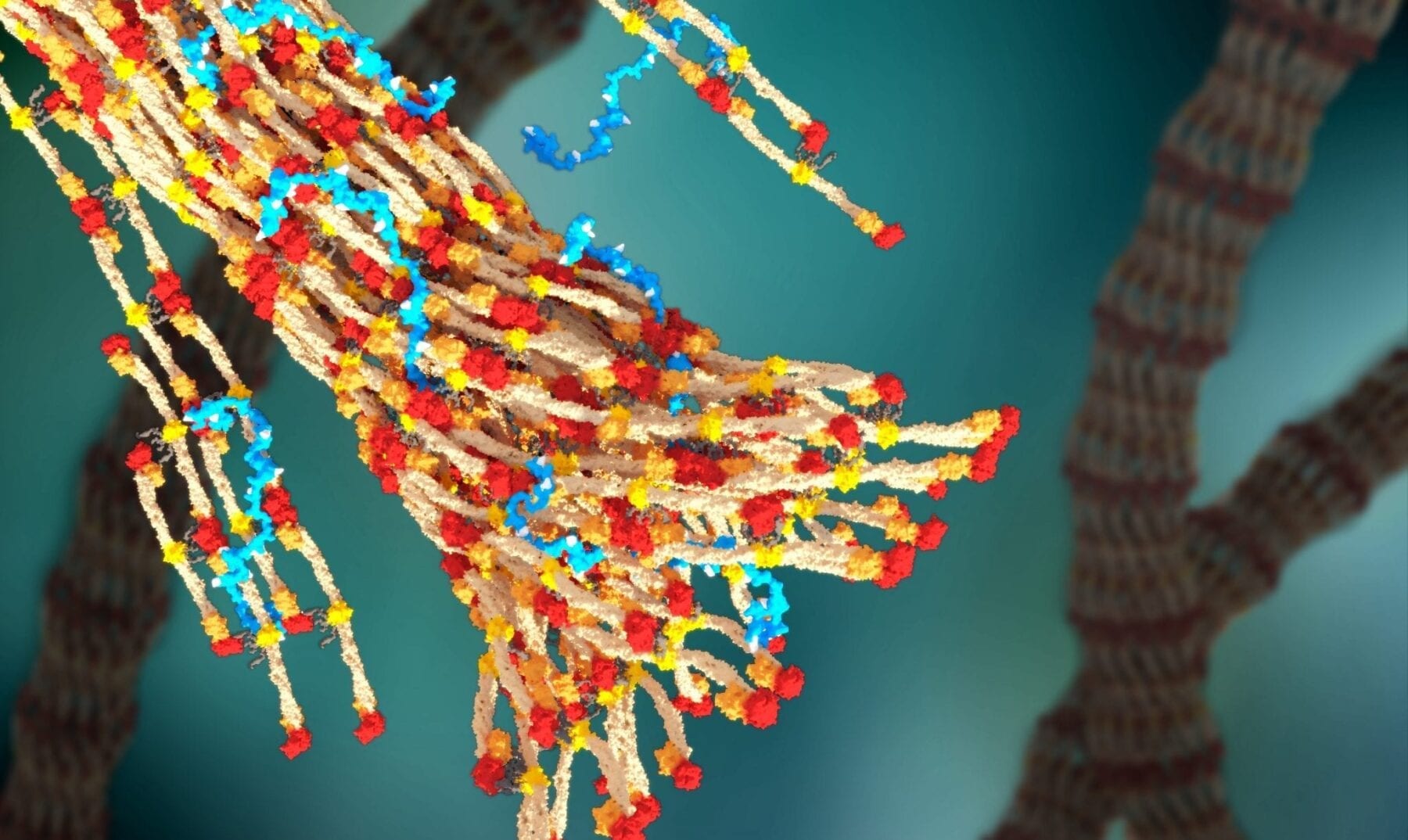

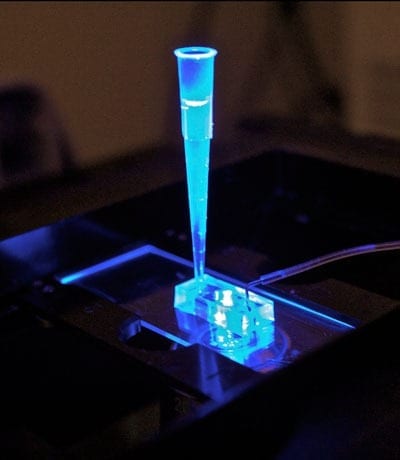

Instead, the research team led by bioengineering professor Kevin Healy is presenting a network of pulsating cardiac muscle cells housed in an inch-long silicone device that effectively models human heart tissue, and they have demonstrated the viability of this system as a drug-screening tool by testing it with cardiovascular medications.

This organ-on-a-chip, reported in a study published today (Monday, March 9) in the journal Scientific Reports, represents a major step forward in the development of accurate, faster methods of testing for drug toxicity. The project is funded through the Tissue Chip for Drug Screening Initiative, an interagency collaboration launched by the National Institutes of Health to develop 3-D human tissue chips that model the structure and function of human organs.

“Ultimately, these chips could replace the use of animals to screen drugs for safety and efficacy,” said Healy.

The study authors noted a high failure rate associated with the use of nonhuman animal models to predict human reactions to new drugs. Much of this is due to fundamental differences in biology between species, the researchers explained. For instance, the ion channels through which heart cells conduct electrical currents can vary in both number and type between humans and other animals.

“Many cardiovascular drugs target those channels, so these differences often result in inefficient and costly experiments that do not provide accurate answers about the toxicity of a drug in humans,” said Healy. “It takes about $5 billion on average to develop a drug, and 60 percent of that figure comes from upfront costs in the research and development phase. Using a well-designed model of a human organ could significantly cut the cost and time of bringing a new drug to market.”

Read more: Bioengineers put human hearts on a chip to aid drug screening

The Latest on: Organ-on-a-chip

[google_news title=”” keyword=”Organ-on-a-chip” num_posts=”10″ blurb_length=”0″ show_thumb=”left”]

via Google News

The Latest on: Organ-on-a-chip

- Group pushes organ donor registrationon April 27, 2024 at 5:00 pm

Anna Fetter of Bedford, mother of the late Jason Fetter, speaks during the Center for Organ Recovery & Education Donate Life event at UPMC Altoona on Tuesday. Organs of Jason, who died in 2014 at the ...

- Go 4 It -- Breaking the Myths: Organ donation and misinformationon April 26, 2024 at 7:56 pm

With over 100,000 people waiting for a life-saving transplant, it is crucial to dispel the myths and provide accurate information about the benefits of organ donation.

- House approves bill to criminalize organ retention without permissionon April 25, 2024 at 6:20 pm

Alabama lawmakers on Thursday advanced a bill making it a crime for medical examiners to retain a deceased person’s organs without family permission.

- CN Bio’s organ-on-a-chip technology boosted by £21m Series B raiseon April 24, 2024 at 9:59 pm

CN Bio is set to expand its PhysioMimix OOC (organ on a chip) technology and research services globally following the first close of a Series B investment round which has raised $21million.

- Opinion: It’s time to stop product and science testing on animalson April 24, 2024 at 3:44 am

Science has given us many marvels. Electricity immediately springs to mind, as does the telephone. The remarkable ease with which we’re able to trace our ancestry is utterly astounding, and ...

- CN Bio raises $21 million to scale up organ-on-a-chip technologyon April 23, 2024 at 5:19 am

CN Bio has raised $21 million in Series B financing to meet increasing demand for its organ-on-a-chip (OOC) solutions.

- Bainbridge, Georgia site raises ethical concerns in researchon April 23, 2024 at 2:08 am

Rather than investing in the expansion of facilities dedicated to NHPs, we should prioritize the development of scientifically robust alternatives.

- Emotions flow as lawmakers, families share stories to push for organ donationon April 17, 2024 at 2:35 pm

Lawmakers were among the dozens in tears at the Capital on Tuesday, as families impacted by organ donations told their stories, both of loss, and of life.

- Organ donors’ families tell their stories at Northwest Health-Porteron April 17, 2024 at 6:57 am

Organ donors’ families and Northwest Health – Porter officials made the case Thursday for signing up as organ donors. For Stephanie Irving, of Palos Heights, Illinois, it was her first visit ...

- Molecular code stimulates pioneer cells to build blood vessels in the bodyon April 16, 2024 at 5:01 pm

The study is published in the journal Nature Communications. A large network of blood vessels distributes blood across organs and thereby ensures that the active cells are supplied with sufficient ...

via Bing News