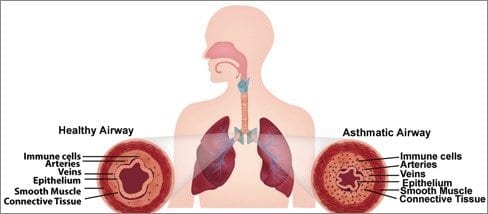

The majority of drugs used to treat asthma today are the same ones that were used 50 years ago. Tissue-level model of human airway musculature could pave way for patient-specific asthma treatments

New drugs are urgently needed to treat this chronic respiratory disease, which causes nearly 25 million people in the United States alone to wheeze, cough, and find it difficult at best to take a deep breath.

But finding new treatments is tough: asthma is a patient-specific disease, so what works for one person doesn’t necessarily work for another, and the animal models traditionally used to test new drug candidates often fail to mimic human responses–costing tremendous money and time.

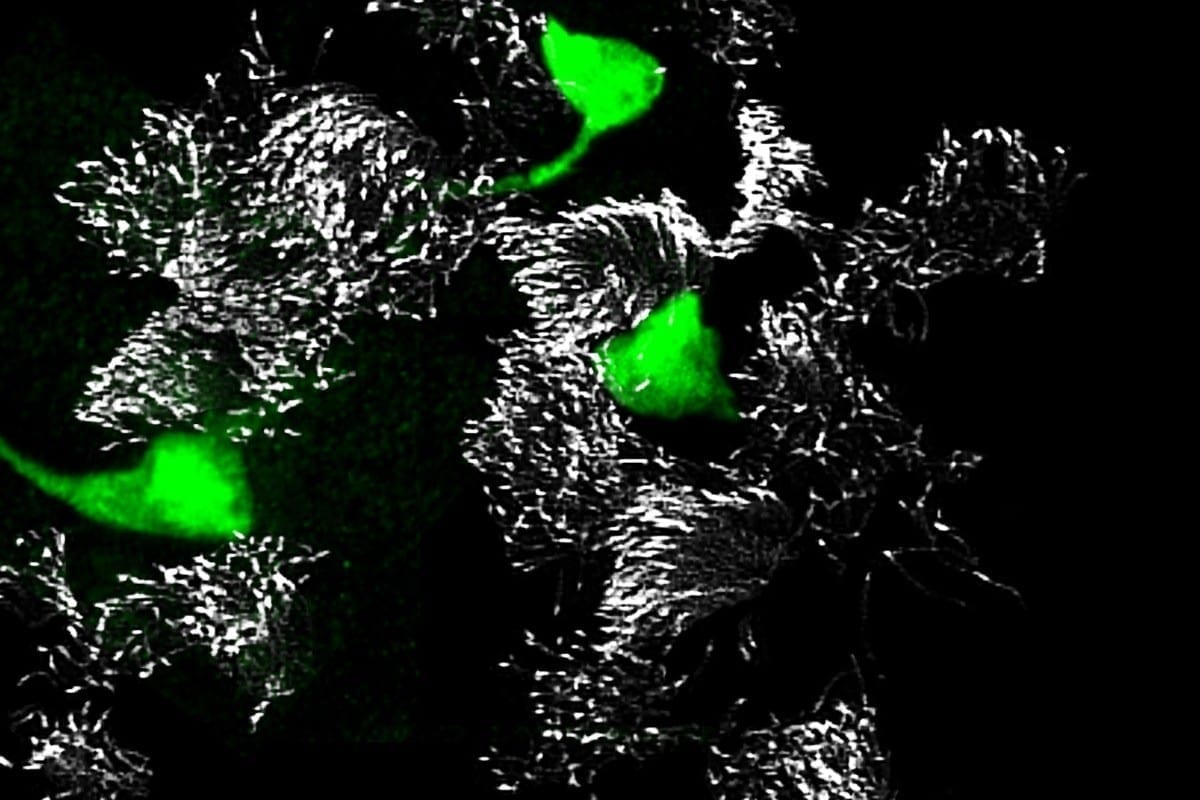

Hope for healthier airways may be on the horizon thanks to a Harvard University team that has developed a human airway muscle-on-a-chip that could be used to test new drugs because it accurately mimics the way smooth muscle contracts in the human airway, under normal circumstances and when exposed to asthma triggers. As reported in the journal Lab on a Chip, it also offers a window into the cellular and even subcellular responses within the tissue during an asthmatic event.

“Every year asthma costs many tens of billions of dollars, significant productivity due to lost work and school days, and even lives,” said senior author Kevin Kit Parker, Ph.D., a Core Faculty member at Harvard’s Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering and Tarr Family Professor of Bioengineering and Applied Physics at the Harvard School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS). Parker leads development of the Wyss Institute’s heart-on-a-chip technology as well and is specifically interested in diseases that affect children. “We were thrilled with how well the chip recapitulated the functioning of the human airway.”

The chip, a soft polymer well that is mounted on a glass substrate, contains a planar array of microscale, engineered human airway muscles, designed to mimic the laminar structure of the muscular layers of the human airway.

To mimic a typical allergic asthma response, the team first introduced interleukin-13 (IL-13) to the chip. IL-13 is a natural protein often found in the airway of asthmatic patients that mediates the response of smooth muscle to an allergen.

Then they introduced acetylcholine, a neurotransmitter that causes smooth muscle to contract. Sure enough, the airway muscle on the chip hypercontracted – and the soft chip curled up – in response to higher doses of the neurotransmitter.

They achieved the reverse effect as well and triggered the muscle to relax using drugs called ?-agonists, which are used in inhalers.

Significantly, they were able to measure the contractile stress of the muscle tissue as it responded to varying doses of the drugs, said lead author Alexander Peyton Nesmith, a Ph.D./M.D. student at Harvard SEAS and the University of Alabama at Birmingham. “Our chip offers a simple, reliable and direct way to measure human responses to an asthma trigger,” he said.

The Latest on: Asthma

[google_news title=”” keyword=”Asthma” num_posts=”10″ blurb_length=”0″ show_thumb=”left”]

via Google News

The Latest on: Asthma

- What Are the Different Types of Asthma?on May 2, 2024 at 9:00 am

There are several types of asthma. They differ based on triggers, age of onset, and treatment response. Knowing your asthma type can direct treatment.

- Too Hot? How to NOT Trigger Your Asthmaon May 2, 2024 at 7:54 am

In contrast, stifling heat can cause the air to become stagnant, which traps pollens, dust, mold and other pollutants that may trigger an asthma flare-up. Also, allergic reactions to the wildfires or ...

- Larger Waists Linked to Greater Likelihood of Asthma Attackson May 2, 2024 at 12:51 am

NHANES data showed a significantly greater median waist circumference among patients with asthma who had asthma attacks compared with those who did not.

- FDA approves asthma drug for treating food allergieson May 1, 2024 at 8:31 pm

A drug newly approved by the Food and Drug Administration to reduce the risk of allergic reactions to food could bring relief to millions across the nation. (April 25, 2024) ...

- Can You Get Asthma as an Adult?on May 1, 2024 at 2:00 pm

Adult-onset asthma is a type of asthma that develops for the first time in adulthood, typically 20 years of age and above. It's slightly more common in people assigned female at birth (9.8%) than in ...

- COVID aside, vaccines and asthma drugs deliver strong quarter for GSKon May 1, 2024 at 1:08 pm

GSK said in the first quarter of 2024, the sales of Specialty Medicines increased, driven by strong HIV and Oncology performances. However, despite increased patient demand, the company noted, ...

- Mapping a way to identify neighborhoods with a high risk of severe child asthmaon May 1, 2024 at 9:20 am

An index of neighborhood environmental and social conditions can help to predict the risk of severe asthma among children at the hyperlocal level, according to a study led by Emily Skeen, MD, a ...

- Senator slams GlaxoSmithKline over cost of asthma inhalerson May 1, 2024 at 8:33 am

Pharmaceutical giant GlaxoSmithKline is sidestepping its pledge to lower asthma inhaler prices, a key senator charged Wednesday, in the latest effort by Democrats to pressure drug companies on the ...

- GSK Expects Higher Profits Boosted By Vaccines, Asthma Drugson May 1, 2024 at 2:33 am

GSK Plc raised its profit forecast for the year as it predicts higher-than-expected sales from HIV, infectious diseases and respiratory drugs.

- Asthma goes prehistoric in AstraZeneca’s Airsupra ad with Walter the Dinoon April 29, 2024 at 10:07 am

Appearing as if he is trailing along behind an asthma patient, Walter the Dino awkwardly fits into elevators and doctors’ offices. However, once Walter’s human friend is prescribed an Airsupra inhaler ...

via Bing News