Imagine a question-and-answer game played by two people who are not in the same place and not talking to each other. Round after round, one player asks a series of questions and accurately guesses the object the other is thinking about.

Sci-fi? Mind-reading superpowers? Not quite.

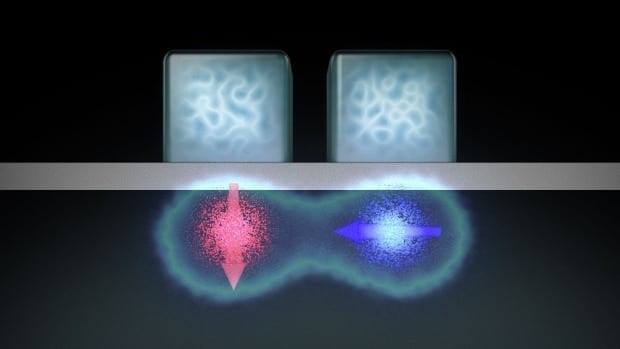

University of Washington researchers recently used a direct brain-to-brain connection to enable pairs of participants to play a question-and-answer game by transmitting signals from one brain to the other over the Internet. The experiment, detailed today in PLOS ONE, is thought to be the first to show that two brains can be directly linked to allow one person to guess what’s on another person’s mind.

“This is the most complex brain-to-brain experiment, I think, that’s been done to date in humans,” said lead author Andrea Stocco, an assistant professor of psychology and a researcher at UW’s Institute for Learning & Brain Sciences.

“It uses conscious experiences through signals that are experienced visually, and it requires two people to collaborate,” Stocco said.

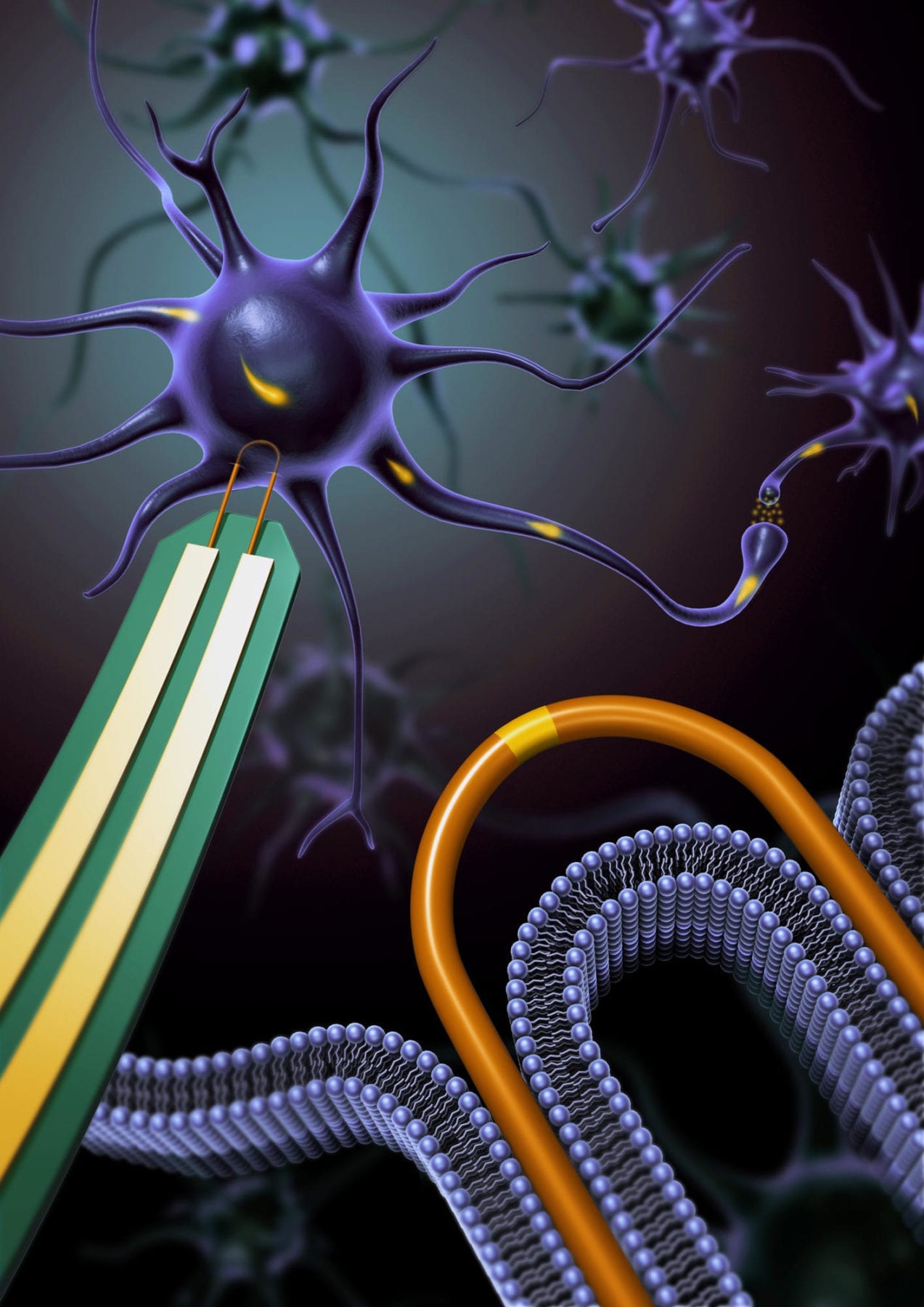

Here’s how it works: The first participant, or “respondent,” wears a cap connected to an electroencephalography (EEG) machine that records electrical brain activity. The respondent is shown an object (for example, a dog) on a computer screen, and the second participant, or “inquirer,” sees a list of possible objects and associated questions. With the click of a mouse, the inquirer sends a question and the respondent answers “yes” or “no” by focusing on one of two flashing LED lights attached to the monitor, which flash at different frequencies.

A “no” or “yes” answer both send a signal to the inquirer via the Internet and activate a magnetic coil positioned behind the inquirer’s head. But only a “yes” answer generates a response intense enough to stimulate the visual cortex and cause the inquirer to see a flash of light known as a “phosphene.” The phosphene — which might look like a blob, waves or a thin line — is created through a brief disruption in the visual field and tells the inquirer the answer is yes. Through answers to these simple yes or no questions, the inquirer identifies the correct item.

The experiment was carried out in dark rooms in two UW labs located almost a mile apart and involved five pairs of participants, who played 20 rounds of the question-and-answer game. Each game had eight objects and three questions that would solve the game if answered correctly. The sessions were a random mixture of 10 real games and 10 control games that were structured the same way.

The researchers took steps to ensure participants couldn’t use clues other than direct brain communication to complete the game. Inquirers wore earplugs so they couldn’t hear the different sounds produced by the varying stimulation intensities of the “yes” and “no” responses. Since noise travels through the skull bone, the researchers also changed the stimulation intensities slightly from game to game and randomly used three different intensities each for “yes” and “no” answers to further reduce the chance that sound could provide clues.

The researchers also repositioned the coil on the inquirer’s head at the start of each game, but for the control games, added a plastic spacer undetectable to the participant that weakened the magnetic field enough to prevent the generation of phosphenes. Inquirers were not told whether they had correctly identified the items, and only the researcher on the respondent end knew whether each game was real or a control round.

“We took many steps to make sure that people were not cheating,” Stocco said.

Participants were able to guess the correct object in 72 percent of the real games, compared with just 18 percent of the control rounds.

Incorrect guesses in the real games could be caused by several factors, the most likely being uncertainty about whether a phosphene had appeared.

Read more: UW team links two human brains for question-and-answer experiment

The Latest on: Brain-to-brain connection

[google_news title=”” keyword=”brain-to-brain connection” num_posts=”10″ blurb_length=”0″ show_thumb=”left”]

via Google News

The Latest on: Brain-to-brain connection

- Sleep resets brain connections -- but only for first few hourson May 1, 2024 at 5:42 pm

During sleep, the brain weakens the new connections between neurons that had been forged while awake -- but only during the first half of a night's sleep, according to a new study.

- New brain connectivity maps offer insights into human consciousnesson May 1, 2024 at 5:00 pm

The study involved high-resolution scans that enabled the researchers to visualize brain connections at submillimeter spatial resolution. This technical advance allowed them to identify previously ...

- Super-detailed map of brain cells that keep us awake could improve our understanding of consciousnesson May 1, 2024 at 11:50 am

A new map of a brain network that sustains wakefulness in humans could help improve our understanding of consciousness.

- Brain imaging study reveals connections critical to human consciousnesson May 1, 2024 at 11:00 am

In a paper titled, "Multimodal MRI reveals brainstem connections that sustain wakefulness in human consciousness," published in Science Translational Medicine, a group of researchers at Massachusetts ...

- Scientists say sleep resets brain connections—but only for first few hourson May 1, 2024 at 8:22 am

During sleep, the brain weakens the new connections between neurons that had been forged while awake—but only during the first half of a night's sleep, according to a new study in fish by UCL ...

- Columbia scientists identify new brain circuit in mice that controls body’s inflammatory reactionson May 1, 2024 at 8:03 am

“We wanted to understand how much farther the brain's knowledge and control of the body's biology went.” The scientists looked for connections the brain might have with inflammation and innate ...

- Move over New York Times, now LinkedIn is adding brain-busting gameson May 1, 2024 at 6:30 am

Rolling out to users globally Wednesday are three games designed to be solved in under five minutes and are refreshed daily. Users will see a new games module in the “LinkedIn News” box in the upper ...

- Exercise Helps Your Brain as Much as Your Bodyon May 1, 2024 at 4:30 am

Instead of just asking questions about how exercise helps our bodies, let’s also consider how it helps our brains ...

- Maintain Your Brain Fitness as You Age by Prioritizing These 6 Thingson April 30, 2024 at 11:52 am

Exercising your mind is just as important as your body. These are the top six things you should practice as you age to help keep your mind sharp.

- UI researchers identify brain area affected by Parkinson’s treatment side effectson April 29, 2024 at 6:43 pm

University of Iowa researchers identified a connection between a routine treatment for Parkinson’s disease and a tendency for some patients to develop increased impulsivity located around a specific ...

via Bing News