Since 1955, The Journal of Irreproducible Results has offered “spoofs, parodies, whimsies, burlesques, lampoons and satires” about life in the laboratory.

Among its greatest hits: “Acoustic Oscillations in Jell-O, With and Without Fruit, Subjected to Varying Levels of Stress” and “Utilizing Infinite Loops to Compute an Approximate Value of Infinity.” The good-natured jibes are a backhanded celebration of science. What really goes on in the lab is, by implication, of a loftier, more serious nature.

It has been jarring to learn in recent years that a reproducible result may actually be the rarest of birds. Replication, the ability of another lab to reproduce a finding, is the gold standard of science, reassurance that you have discovered something true. But that is getting harder all the time. With the most accessible truths already discovered, what remains are often subtle effects, some so delicate that they can be conjured up only under ideal circumstances, using highly specialized techniques.

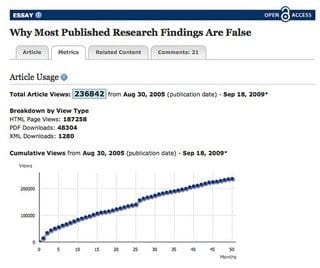

Fears that this is resulting in some questionable findings began to emerge in 2005, when Dr. John P. A. Ioannidis, a kind of meta-scientist who researches research, wrote a paper pointedly titled “Why Most Published Research Findings Are False.”

Given the desire for ambitious scientists to break from the pack with a striking new finding, Dr. Ioannidis reasoned, many hypotheses already start with a high chance of being wrong. Otherwise proving them right would not be so difficult and surprising — and supportive of a scientist’s career. Taking into account the human tendency to see what we want to see, unconscious bias is inevitable. Without any ill intent, a scientist may be nudged toward interpreting the data so it supports the hypothesis, even if just barely.

The effect is amplified by competition for a shrinking pool of grant money and also by the design of so many experiments — with small sample sizes (cells in a lab dish or people in an epidemiological pool) and weak standards for what passes as statistically significant. That makes it all the easier to fool oneself.

Paradoxically the hottest fields, with the most people pursuing the same questions, are most prone to error, Dr. Ioannidis argued. If one of five competing labs is alone in finding an effect, that result is the one likely to be published. But there is a four in five chance that it is wrong. Papers reporting negative conclusions are more easily ignored.

Putting all of this together, Dr. Ioannidis devised a mathematical model supporting the conclusion that most published findings are probably incorrect.

The Latest on: Research results

[google_news title=”” keyword=”Research results” num_posts=”10″ blurb_length=”0″ show_thumb=”left”]

via Google News

The Latest on: Research results

- New Research Suggests Most Dogs Are in Need of More Friendson April 27, 2024 at 7:14 am

Some dogs are dog aggressive and don't get along with other dogs. Other dogs are dog selective and choosy about the other dogs and humans they want to interact with. And some dogs are dog social and ...

- The AI-fueled stock market bubble will crash in 2026, research firm sayson April 27, 2024 at 5:16 am

"This dynamic played out around both the dot-com bubble of the late 1990s and early 2000s and the Great Crash of 1929," Capital Economics said.

- UC system: We would not “create a secret loophole” to pay research scholars less | Opinionon April 27, 2024 at 5:00 am

UAW advocated for the current salary scales and will also negotiate any future compensation changes on its members’ behalf.” ...

- Higher For Longer? Focus On The Balance Sheeton April 27, 2024 at 4:00 am

The Fed may need to choose between fighting inflation and protecting economic growth. Read how REITs with strong balance sheets are positioned to navigate macro challenges.

- Can nasal Neosporin fight COVID? Surprising new research suggests it workson April 27, 2024 at 2:30 am

A potential treatment for COVID-19 may have been hiding in our medicine cabinets, a new study in PNAS has found ...

- What's the Worst Age to Start Taking Social Security? Here's What the Research Says.on April 27, 2024 at 12:00 am

The age at which you begin claiming Social Security will affect your monthly income for the rest of your life, so it's important to take this decision seriously. You generally only get one chance to ...

- Lam Research Outperforms Expectationson April 26, 2024 at 9:20 am

The March 2024 quarter saw a slight drop in revenue year over year, but AI initiatives have management projecting 19% gains next quarter.

- Robert F. Kennedy Jr. is wrong about a ban on NIH research about mass shootingson April 26, 2024 at 7:30 am

CDC, NIH, and other federal agencies have funded millions of dollars in gun-related research, including studies on mass shootings.

- Scientists inspired the right guardrails for nuclear energy, the internet, and DNA research. Let them do the same for AIon April 26, 2024 at 5:53 am

Like with other tech that exposed humanity to possible annihilation, a Pugwash conference for AI scientists is urgently needed.

- Columbia research assistant reacts to ongoing protests: 'It's been a nightmare'on April 26, 2024 at 4:49 am

Columbia University research assistant Omer Lubaton Granot on the upcoming rally to bring Israeli voices to the school, advocating to bring home hostages and asking for peace and respect.

via Bing News