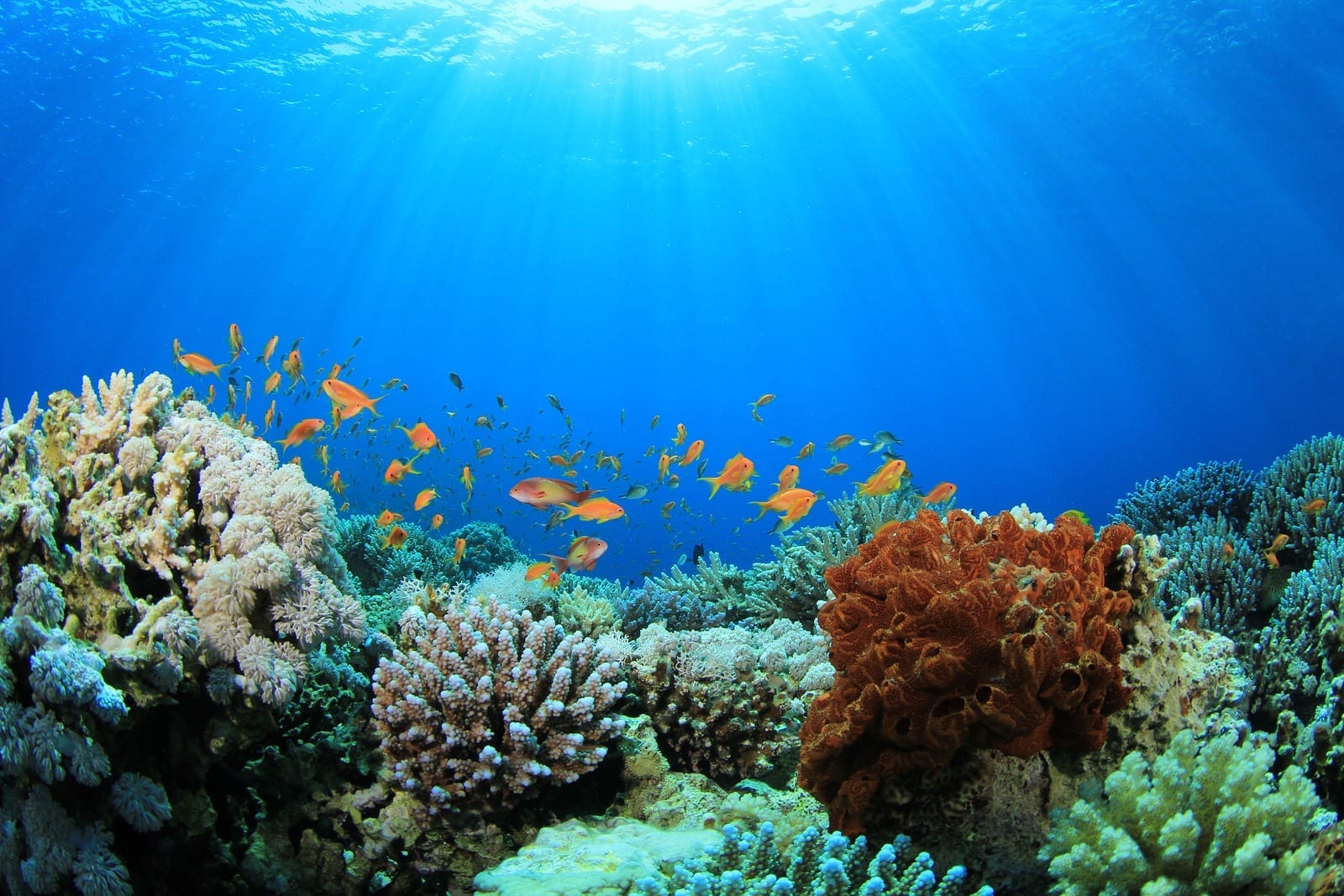

Why take a chance when one of the world’s most vital ecosystems is already disappearing?

As it stands, things don’t look good for the world’s coral. We’ve lost 40% of the world’s reefs already, and every forecast shows the situation getting worse. As well as traditional threats like overfishing and coastal development, corals now have to contend with climate change, which not only warms the water but also makes it more acidic.

That’s why Mary Hagedorn thinks we need to move beyond traditional conservation efforts to something more radical: artificial reproduction. Hagedorn, a marine scientist with the Smithsonian Institution, is building the world’s largest repository of coral sperm (and soon coral eggs and embryos) in hopes of one day reconstructing species from scratch and replacing what we’ve lost.

To some, that might seem like an ambitious and perhaps unnecessary undertaking. But Hagedorn, who’s based in Hawaii, argues that coral reefs play a special part in the ocean and require all the effort we can muster. For one, reefs are home to a quarter of all ocean creatures and help maintain biodiversity. They also provide people protection against coastal surges and boost marine tourism. The Great Barrier Reef alone is said to generate about $6 billion for Australia’s economy.

“If coral reefs fail around the world, we have no idea how that ripple effect will impact the rest of the oceans,” she says. “And healthy oceans are really important to our survival.”

Coral—a unique form of life that is part animal, part vegetable, and part mineral—is capable of reproducing both asexually and sexually. The simplest way is to snap off a piece and regrow it, like you were taking a cutting from the garden. But it’s not the best way, Hagedorn says. When you clone a plant, you’re simply reproducing it as it is, not breeding it in some new genetic form that’s potentially better.

“You can get more coverage, but you can [run] into problems, especially if diseases break out. One disease can devastate all the work you’ve done,” she says. “Having things that are produced sexually is often better, because you can throw the genetic dice and possibly a new adaptation will come along.”

For example, some years ago, staghorn coral fused with elkhorn coral to produce a new species called Acropora prolifera, which is now prevalent in the Caribbean. That’s good, because the hybrid is more heat-tolerant and surge-resistant than either of the varieties would be on its own.

Read more: This Woman Is Building A Sperm Bank For Coral Reefs So We Can Revive Them Once They Die

The Latest on: Coral Reefs

[google_news title=”” keyword=”Coral Reefs” num_posts=”10″ blurb_length=”0″ show_thumb=”left”]

via Google News

The Latest on: Coral Reefs

- Technology and data initiatives aim to preserve the world’s declining coral reefson April 26, 2024 at 1:38 am

Coral reefs have been described as the “rainforests of the ocean”. Which is why these two initiatives to try and preserve them are so important.

- A coral-bleaching event is devastating reefs globally − threatening tiny creatures whose beauty and biology have shaped human cultures for centurieson April 25, 2024 at 10:02 am

Coral’s biological uniqueness and central role in sustaining other forms of life, including humans, are reasons enough to preserve it. And scientists are making extraordinary efforts, such as ...

- It’s One of the Last Pristine Coral Reefs on Earth. Should We Be Visiting It?on April 24, 2024 at 12:15 pm

The Raja Ampat archipelago of Indonesia looms large in the imaginations of underwater adventurers. But by visiting its relatively untouched reefs are we protecting them—or threatening them?

- Culling predatory starfish conserves coral on the Great Barrier Reefon April 24, 2024 at 11:00 am

Targeted culling of crown-of-thorns starfish has resulted in parts of the Great Barrier Reef maintaining and even increasing coral cover, leading researchers to call for the programme to be dramatical ...

- New algorithm solves century-old problem for coral reef scientistson April 23, 2024 at 7:21 am

An algorithm developed by a Florida Tech graduate student creates a new ecological survey method that allows scientists to unlock important historical data from a vast trove of coral-reef photographs ...

- More than coral: The unseen casualties of record-breaking heat on the Great Barrier Reefon April 22, 2024 at 8:38 am

In past bleaching events on the Great Barrier Reef, the southern region has sometimes been spared worst of the bleaching. Not this time. This year's intense underwater heat has triggered the most ...

- These coral reefs suffered major damage. Watch how restoration efforts helped bring them backon April 19, 2024 at 10:57 am

Coral reefs offer crucial habitat for marine creatures and protection for coastal communities, but face a long list of threats due to human activity. One restoration project in Indonesia demonstrates ...

- UN envoy says of the threat to coral reefs: 'Are we faced with a colossal ecosystem tragedy? Yes'on April 16, 2024 at 11:07 am

ATHENS, Greece -- The world is not doing enough to protect coral reefs, the United Nations’ special envoy for the ocean said Tuesday in defense of the marine ecosystems that protect biodiversity, ...

- Most coral reef areas experienced bleaching in past year: Researchon April 15, 2024 at 12:34 pm

Coral reefs around the globe experienced a mass bleaching event in the past year as the ocean continues to heat, according to new research. Mass bleaching has been reported in coral reefs in at ...

- Scientists say coral reefs around the world are experiencing mass bleaching in warming oceanson April 15, 2024 at 8:58 am

Reef scientists say coral reefs around the world are experiencing global bleaching for the fourth time due to prolonged warming of the oceans ...

via Bing News