- Image by AlphachimpStudio via Flickr

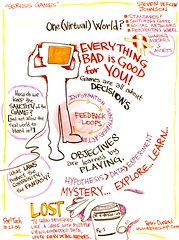

WHERE do good ideas come from? That is the question posed by Steven Johnson, a writer known for the agility with which he makes interdisciplinary analogies, in his latest book. His “natural history of innovation” provides a taxonomy of seven ways in which new ideas can sprout from old ones. But this is no management text: for each of his seven patterns of innovation, Mr Johnson provides wide-ranging examples from technology, the natural world and culture.

The first of the patterns is “the adjacent possible”: the innovations that build logically on previous breakthroughs. In technology, this results in the common phenomenon of several people inventing the same thing at the same time, because it seemed the obvious next step. Similarly, life itself emerged as a cascade of increasing complexity, and the forking paths of evolution allow one innovation to lead to another, such as the semi-lunate carpal bone that made velociraptors more dexterous predators, but subsequently led to the evolution of winged, flying birds. Cultural and social life is also an exploration of the adjacent possible, as one unexpected door opens and then leads to others.

In a similar vein Mr Johnson explores the “liquid networks” that foster innovation, whether online, in coffeehouses or in ecosystems, and the “slow hunch” whereby an idea develops slowly and often wrongly, before suddenly becoming the right answer to something. He also examines the benefits of serendipity and error, which can each lead to beneficial insights; the notion of “exaptation”, in which an innovation in one field unexpectedly upends another (Gutenberg’s press combined ink, paper, movable type and, crucially, the machinery of the wine-press); and “platforms”, from operating systems to coral reefs, which provide fertile environments for new developments.

Readers of Mr Johnson’s previous books will note the recurrence of several of his favourite themes, such as the similarity between the structure of a city and that of the brain. This book is in many ways a grand synthesis of his previous works. Patterns of innovation, Mr Johnson suggests, are fractal: “they reappear in recognisable form as you zoom in and out, from molecule to neuron to pixel to sidewalk.” Only in the final paragraph does he provide some suggestions about how to apply these ideas in one’s own life.

Kevin Kelly’s book is even more ambitious. It is a sweeping theory of technology that presents it not as a series of inventions by humans, but as a living force with its own needs and tendencies. It might sound facile to ask what technology “wants”, but Mr Kelly, who was founding editor of Wired magazine, makes a case for the desire of the “technium”, as he dubs the ecosystem of technologies, to grow in complexity and colonise new areas, just like life itself. He argues that just as water “wants” to flow downhill and life tends to fill available ecological niches, technology similarly “wants” to expand and evolve. We have no choice but to embrace it, he says, because we are already symbiotic with it; technology underpins civilisation.

Related articles

- Innovation and technology: Well, what a good idea! (economist.com)

- Seven ways to make a new thing (newscientist.com)