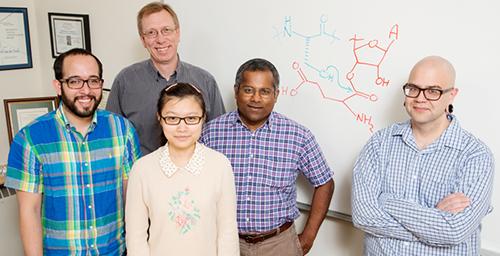

Credit: L. Brian Stauffer

Opens up new avenues of research into thousands of similar molecules, many of which are likely to be medically useful.

Researchers report in the journal Nature that they have made a breakthrough in understanding how a powerful antibiotic agent is made in nature. Their discovery solves a decades-old mystery, and opens up new avenues of research into thousands of similar molecules, many of which are likely to be medically useful.

The team focused on a class of compounds that includes dozens with antibiotic properties. The most famous of these is nisin, a natural product in milk that can be synthesized in the lab and is added to foods as a preservative. Nisin has been used to combat food-borne pathogens since the late 1960s.

Researchers have long known the sequence of the nisin gene, and they can assemble the chain of amino acids (called a peptide) that are encoded by this gene. But the peptide undergoes several modifications in the cell after it is made, changes that give it its final form and function. Researchers have tried for more than 25 years to understand how these changes occur.

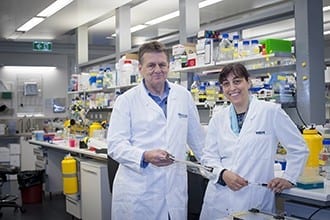

“Peptides are a little bit like spaghetti; they’re too flexible to do their jobs,” said University of Illinois chemistry professor Wilfred van der Donk, who led the research with biochemistry professor Satish K. Nair. “So what nature does is it starts putting knobs in, or starts making the peptide cyclical.”

Special enzymes do this work. For nisin, an enzyme called a dehydratase removes water to help give the antibiotic its final, three-dimensional shape. This is the first step in converting the spaghetti-like peptide into a five-ringed structure, van der Donk said.

The rings are essential to nisin’s antibiotic function: Two of them disrupt the construction of bacterial cell walls, while the other three punch holes in bacterial membranes. This dual action is especially effective, making it much more difficult for microbes to evolve resistance to the antibiotic.

Previous studies showed that the dehydratase was involved in making these modifications, but researchers have been unable to determine how it did so. This lack of insight has prevented the discovery, production and study of dozens of similar compounds that also could be useful in fighting food-borne diseases or dangerous microbial infections, van der Donk said.

The Latest on: Antibiotics

[google_news title=”” keyword=”antibiotics” num_posts=”10″ blurb_length=”0″ show_thumb=”left”]

via Google News

The Latest on: Antibiotics

- COVID-19 Worsened overuse of antibiotics, WHO raises concern over dangers of Antimicrobial Resistanceon April 27, 2024 at 5:08 am

The use of antibiotics was highly seen among patients with severe or critical COVID-19, with a global average of 81%.

- New antibiotics aren’t being fully used, study findson April 23, 2024 at 2:02 pm

A new study shows that, despite having newer options for antibiotic-resistant infections, US clinicians are still frequently opting for less optimal older, generic antibiotics.

via Bing News