The collar of the wild is coming.

And in the same way that the smartphone changed human communications, what might be called the “smart collar” — measuring things that people never could before about how animals move and eat and live their lives — could fundamentally transform how wild populations are managed, and imagined, biologists and wildlife managers say.

The collars, in development in academia and intended for commercial production in the next few years, use a combination of global positioning technology and accelerometers for measuring an animal’s metabolic inner life in leaping, running or sleeping. From the safari parks of Africa to urbanized zones on the edge of wildlands across the American West — places where widespread interest in the devices has already been voiced, scientists said — the mysteries of the wild might never be the same.

“What you end up with is a diary for the animal, a 24-hour diary that says he spent this much time sleeping, and we know from the GPS where that was,” said Terrie Williams, a professor of biology at the University of California, Santa Cruz, and one of three co-investigators on the project. “Then he woke up and went for a walk over here. He caught something over here. He ate something and we know what it was because the signatures we get for a deer kill vs. a rabbit kill are very different.”

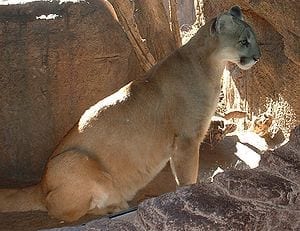

And Mischief, a 10-year-old captive female mountain lion here in Colorado, may have provided a crucial link in the chain of research. The 121-pound cat, orphaned shortly after birth when her mother was shot by an elk hunter and raised by the state as a study animal, paced on a modified treadmill on Monday morning while munching venison morsels hand-fed in reward by her trainer, Lisa Wolfe, a veterinarian at Colorado Parks and Wildlife.

“We got the data point,” Professor Williams said, looking up from her laptop, which was measuring Mischief’s oxygen intake while the cat moved at three kilometers per hour. She said the accumulation of data points for mountain lions — what she called “a library of signatures” for every kind of movement — was the first phase of the project. One of her graduate students is developing the next iteration of the collar for wolves and coyotes, two other animals that live in proximity to people across wide swaths of the nation.

That mountain lions do not normally eat and walk at the same time is just one of the wrinkles that will require a fine calculation, in adjusting for the added calories that Mischief burned in gulping her treats. Training her and her brother Rascal to accept the treadmill at all, which scientists said was also a first for adult mountain lions, took eight months of acclimation and reward at the state research station 65 miles north of Denver.

“At first, it was the classic walking-and-chewing-gum-at-the-same-time problem — they’d take a bite, then stop,” said Michael W. Miller, a senior wildlife veterinarian at Colorado Parks and Wildlife.

The lions here, since their capture, have been actively trained in a research project on the effects of a neurological disease, chronic wasting, which infects many of the deer, elk and moose that lions eat. They have been fed mostly on infected animals donated by hunters, and trained— in balancing, recognizing geographic shapes, and now on treadmills — as a way of assessing their mental and physical health. Dr. Wolfe said that so far no ill-effects had been detected. Professor Williams said she searched for two years for any lions that might be trainable for her motion tests before finding Rascal and Mischief.

But the goal of the project, which was financed by about $800,000 in grants from the National Science Foundation, is not just to gain knowledge about animals that might be captured and fitted with the devices. What the researchers are aiming for is no less than a platform for predicting wild behavior, a human dream since the first hunter-ancestors ventured onto the African savannah.