In the medical community, sepsis can be a scary word. It means the body’s immune system is going into overdrive trying to kill a blood-borne bacterial infection. It’s an easily treated condition, but if left untreated can kill a person in as little as two days.

The even scarier part? Normal methods of detecting sepsis take at least that long.

But researchers in the Texas Tech University Department of Chemistry & Biochemistry have found a new way to significantly reduce that detection time, giving medical professionals a greater window of time in which to treat the patient.

“Normally when you detect sepsis, you do it through bacterial culture; that takes two days on the short end to 15 days on the long end,” said Dimitri Pappas, an associate professor of chemistry. “Most people die of sepsis at two days. The detection currently is on the exact same time scale as mortality, so we’re trying to speed that up.

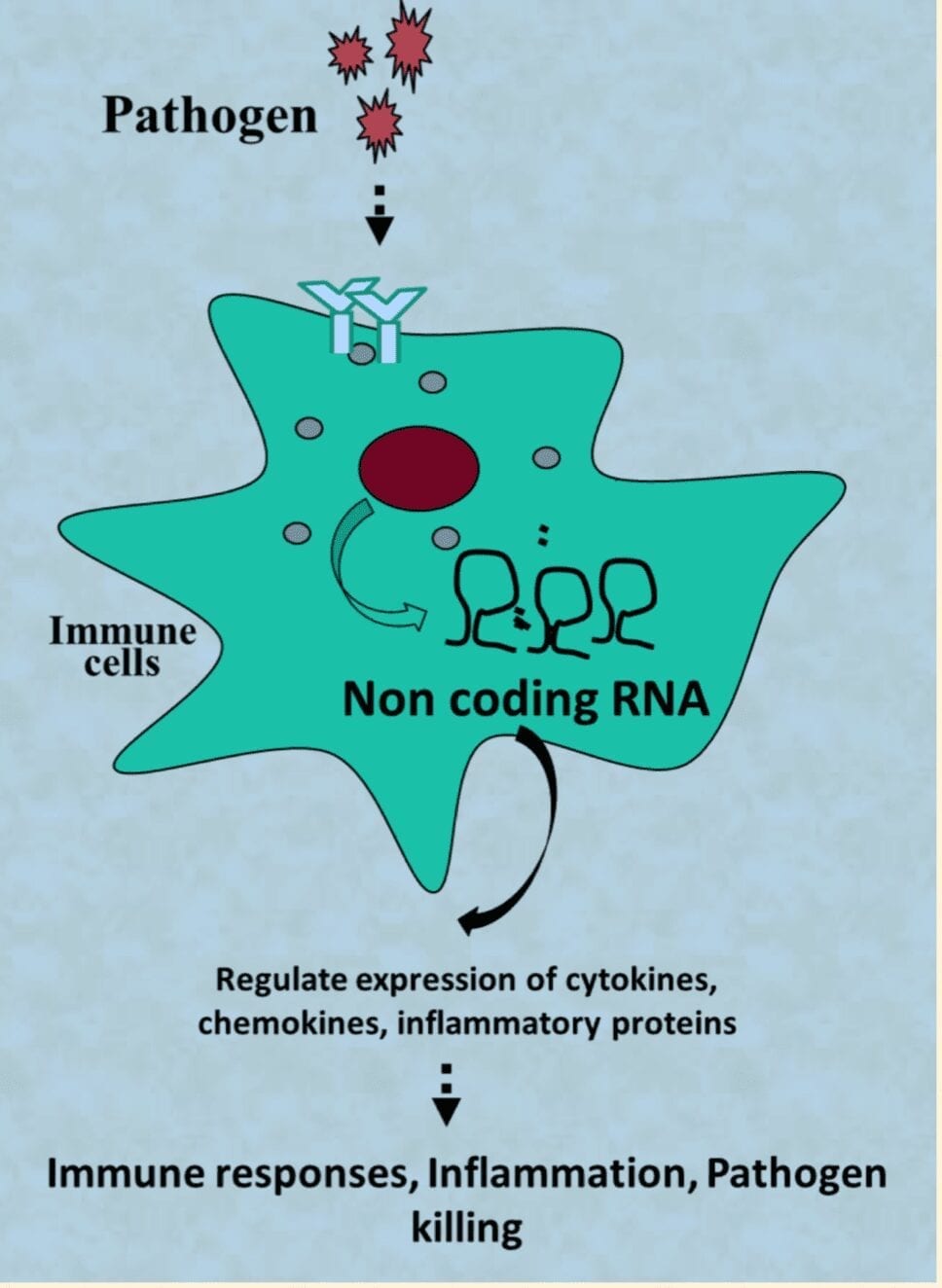

“Instead of the bacteria, we’re looking at the body’s immune response to those bacteria, because that’s what you really care about. The bacteria cause the infection, but it’s the body’s response that causes sepsis.”

The problem

Sepsis is a major concern in the U.S. health care industry. It’s one of the highest causes of death in hospitals because it is most likely to occur in people already there.

“Most of the time when you have a pretty serious infection of the blood, your body can handle it,” Pappas said. “In the elderly, in people who are immune-compromised – people who have had surgeries, for example, or burns or they’re already fighting off infection – and in children as well, you see a runaway immune response where the body’s act of saving itself can actually be lethal.”

It begins with what’s called systemic inflammatory response syndrome – that’s the body ramping up the immune system to fight the bacteria. From there, it progresses into sepsis and eventually septic shock, in which blood pressure plummets, organs fail and eventually the patient dies.

“It is estimated there are 1 million new cases of sepsis in hospitalized patients per year in the United States,” said Dr. John Griswold, professor and chair emeritus in the Department of Surgery at the Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center. “Sepsis is the leading cause of death in intensive care units in the United States, and patients with the diagnosis of sepsis have a minimum of a 30 percent chance of dying of their disease; if their vital organ systems – brain, heart, lungs, liver, kidneys – are affected, they have a 70 percent chance of dying. The elderly have the highest rate and, in some studies, death is over 85 percent in those over the age of 75.”

In addition to mortality, sepsis can result in amputation of a limb or prolonged hospitalization. Griswold said it’s considered one of the most costly diseases in health care, amounting to a staggering $22 billion to $25 billion each year, a cost that’s increasing by 11 to 12 percent each year.

Sepsis is regularly detected through a patient’s abnormal body temperature and rapid heart and breathing rates.

“Those are all incredibly crude measurements, so it’s not a precise measurement at all,” Pappas said. “It leads to a lot of false positives.”

A bacterial culture is done to verify the diagnosis, but because doctors know the bacterial culture likely will take longer than a septic patient’s life span, they often order treatment immediately.

“The way they treat sepsis right now is through a massive antibiotic administration,” Pappas said. “That’s good, actually, but if you do it prophylactically and when it’s not needed, you’re basically helping create drug-resistant bacteria. So there’s a need to detect sepsis and to treat it but not to over treat it as well, because over treating it leads to additional problems.”

The solution

To successfully treat septic patients, doctors need two critical pieces of information: the microorganism causing the infection and whether it can be eradicated by antibiotics.

“Waiting for that information over several days is one of the main problems and reasons for the devastating outcomes,” Griswold said. “Dr. Pappas has developed a test that should give us at least the indication of bacterial invasion within a matter of hours as opposed to days. The sooner we have an indication of microorganism invasion, the sooner we are on the path to successful treatment of these very sick patients.”

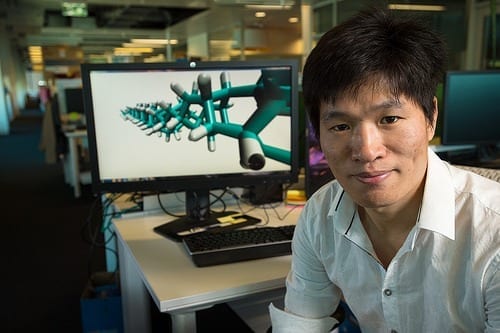

Working in a field known as microfluidics, Pappas and graduate student Ye Zhang recently filed a provisional patent for a tiny chip that can speed up the detection process.

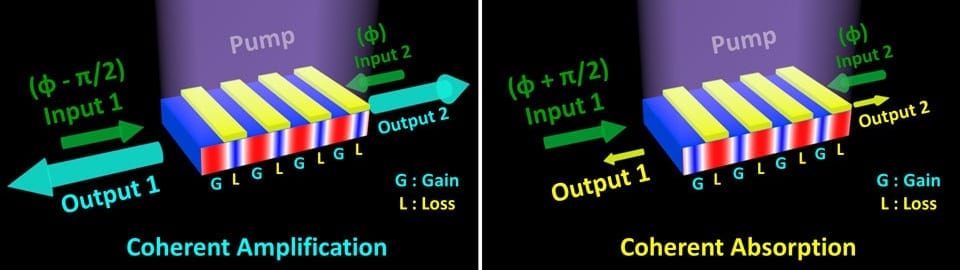

“We make tiny glass and plastic chips that perform fluid operations just like a circuit on your computer does electronic operations,” Pappas said. “We can take a blood sample, introduce it into this chip and capture one cell type or move fluids around and add chemicals to dye the cells certain colors and do diagnostic measurements.”

Using their chip, a sepsis diagnosis can be confirmed in just four hours.

“That rapid detection will let doctors intervene sooner and intervene when necessary, but it also allows them not just to detect it but to follow up treatment,” Pappas said. “If a patient is septic and they’re identified as such, and then you give them this heavy course of antibiotics, you can follow and retest them over time to make sure the body’s response is returning to normal.”

The chip requires less than a drop of blood for an accurate test.

“It’s so minimal we could do this multiple times throughout the course of the treatment of the patient,” Pappas said. “If they’re not septic at hour zero, but they still look septic by other methods, we could test them in six hours and see if they’ve progressed or not.”

The chips are designed to look for the activation of certain white blood cells, which would indicate the immune system was going to work to fight the infection.

At this point, all testing has been done with the help of stem cells.

“We have stem cells that we transform into white blood cells, then we trick them into thinking there’s an infection,” Pappas said. “We add those infection-response blood cells to human blood in the concentrations we want and the time frame we want.”

The blood is then tested to see if the chip registers it as septic.

“That allows us to refine the technique to make sure it’ll work, because human samples are far more variable as far as the protein content of the blood, the stress factors in the blood,” Pappas said. “Before moving to humans, we had to show it’ll work in the first place.”

Because of the chip’s success, the next step is to test with human blood. And thanks to a collaboration with Dr. Griswold, Pappas will start enrolling patients in November.

Pappas would like to see the device used in health care centers everywhere.

“Ultimately, this type of work – for it to be successful – has to be commercialized,” he said. “It has to be out there in the hands of physicians. We’re going to pilot it at the Health Sciences Center, but ultimately we want it to be adopted outside the walls of this building and outside the city of Lubbock.”

Pappas said he was ecstatic when he realized the chip worked and is eager to see its future.

“It’s not always that the universe works in your favor,” he said. “This time everything kind of lined up the way it should have.”

Learn more: THIS NEW TECHNOLOGY COULD PREVENT A LEADING CAUSE OF DEATH

The Latest on: Sepsis

[google_news title=”” keyword=”sepsis” num_posts=”10″ blurb_length=”0″ show_thumb=”left”]

via Google News

The Latest on: Sepsis

- AHA blog shares ways to prevent pediatric sepsison April 26, 2024 at 12:18 pm

Pediatric sepsis is "an aggressive and unrelenting adversary that knows neither geographic nor demographic bounds," writes Chris DeRienzo, M.D., AHA’s senior vice president and chief physician ...

- Prevention Is the Prescription for Reducing Pediatric Sepsison April 26, 2024 at 9:52 am

As a pediatrician, I've seen the impact of pediatric sepsis firsthand — it's an aggressive and unrelenting adversary that knows neither geographic nor demographic bounds. Sepsis is also harder to ...

- Boy, 3, would have survived sepsis with quick hospital referralon April 26, 2024 at 1:58 am

Boy, 3, would have survived sepsis with quick hospital referral - Isaac Onyeka, from Loughton, became unresponsive at home after contracting a Strep A infection which led to sepsis ...

- Ingredient found in cakes, chewing gum and drinks is ‘toxic to the gut and could trigger sepsis’on April 25, 2024 at 7:54 am

FOOD sweetener neotame can damage the gut and cause serious illness, a study suggests. The e-number chemical is thousands of times sweeter than sugar and is increasingly used in place of ...

- Deepull debuts point of care sepsis detection UllCORE systemon April 25, 2024 at 4:41 am

"Deepull debuts point of care sepsis detection UllCORE system" was originally created and published by Medical Device Network, a GlobalData owned brand.

- deepull unveils 1 hour, direct-from-blood multiplex PCR test for 95% of sepsis-causing pathogens at ESCMID 2024on April 25, 2024 at 12:28 am

UllCORE is designed to transform life-saving clinical decision making for sepsis patients Barcelona, Spain – 25 April 2024 – deepull, a medical diagnostics company developing culture-free diagnostic ...

- Sepsis Diagnostics Market is Expected to Reach $890 million | MarketsandMarkets™on April 24, 2024 at 5:29 am

Sepsis Diagnostics market in terms of revenue was estimated to be worth $634 million in 2024 and is poised to reach $890 million by 2029, growing at a CAGR of 7.0% from 2024 to 2029 according to a ...

- Medical Monday: Sepsison April 23, 2024 at 9:36 am

In this week’s Medical Monday. we learn more about Sepsis Syndrome and how the body can have negative responses to an infection.

- Superfit gran's sepsis warning after 'flu' left her fighting for life just days lateron April 23, 2024 at 1:35 am

Dee Thomas, 65, from Perthshire, was left fighting for her life after what she thought was a bout of 'flu' turned out to be a serious infection that began attacking her heart and spine.

via Bing News