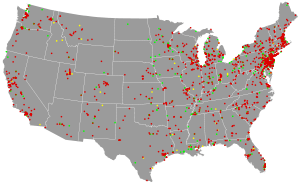

- Image via Wikipedia

Chemists are usually asked to invent a solution, but without considering hazardous by-products. Green chemists now are doing both with success, but will it take regulations to enforce the approach broadly?

Back in the days when better living through chemistry was a promise, not a bitter irony, nylon stockings replaced silk, refrigerators edged out iceboxes, and Americans became increasingly dependent on man-made materials. Today nearly everything we touch—clothing, furniture, carpeting, cabinets, lightbulbs, paper, toothpaste, baby teethers, iPhones, you name it—is synthetic. The harmful side effects of industrialization—smoggy air, Superfund sites, mercury-tainted fish, and on and on—have often seemed a necessary trade-off.

But in the early 1990s a small group of scientists began to think differently. Why, they asked, do we rely on hazardous substances for so many manufacturing processes? After all, chemical reactions happen continuously in nature, thousands of them within our own bodies, without any nasty by-products. Maybe, these scientists concluded, the problem was that chemists are not trained to think about the impacts of their inventions. Perhaps chemistry was toxic simply because no one had tried to make it otherwise. They called this new philosophy “green chemistry.”

Green chemists use all the tools and training of traditional chemistry, but instead of ending up with toxins that must be treated and contained after the fact, they aim to create industrial processes that avert hazard problems altogether. The catch phrase is “benign by design”.

Progress without pollution may sound utterly unrealistic, but businesses are putting green chemistry into practice. Buying, storing, and disposing of hazardous chemicals is expensive, so using safer alternatives makes sense. Big corporations—Monsanto, Dow, Merck, Pfizer, DuPont—along with scrappy start-ups are already applying green chemistry techniques. There have been hundreds of innovations, from safer latex paints, household cleaning products and Saran Wrap to textiles made from cornstarch, and pesticides that work selectively, by disrupting the life cycles of troublesome insects. Investigators have also developed cleaner ways of decaffeinating coffee, dry-cleaning clothes, making Styrofoam egg cartons, and producing drugs like Advil, Zoloft and Lipitor.

Over the past 15 years, green chemistry inventions have reduced hazardous chemical use by more than 500 million kilograms. Which sounds great, until you consider that every day the U.S. produces or imports about 33.5 billion kilograms of chemicals. The annals of green chemistry are full of crazy, fascinating stories, like a plan to turn the unmarketable potatoes from Maine’s annual harvest into biodegradable plastics. Still, a decade after the phrase was coined, green chemistry patents made up less than 1 percent of patents in chemical-heavy industries.

What will it take for green chemistry to be more than the proverbial drop in the bucket, a bucket full of toxic sludge? Some experts believe that the answer is government intervention—not only laws that ban harmful chemicals, but laws that simply require chemical manufacturers to reveal safety data and let the market do the rest. “Right now, companies that make chairs or cars or lipstick don’t know which of the chemicals they incorporate into their products are safe,” says Michael Wilson, an environmental health scientist at the University of California, Berkeley. “Once that information becomes available, there will be a demand for less toxic ingredients.”

That question—to regulate or not to regulate—has split the community of green chemistry advocates. Some oppose making green chemistry mandatory: its principles are so sensible and cost-effective, they believe, that industry will implement them voluntarily. Others, such as Wilson, disagree. The key, he asserts, is “fundamental chemicals policy reform in the U.S.”

Now is a critical time: After decades of inaction, the U.S. government is finally examining more aggressively the health effects of common chemicals. The ambitious Safe Chemicals Act, unveiled last month in the U.S. Senate, would require all industrial chemicals to be proved safe, creating a strong incentive for the development of less harmful alternatives. And the President’s Cancer Panel released a landmark report earlier this month decrying the “grievous harm” done by cancer-causing chemicals such as bisphenol A in food and household products.

The stakes are high, higher than most people realize. The companies that make the 80,000 chemicals that circulate in our world are rarely required to do safety testing, and government agencies are relatively powerless. “This is pretty shocking, since most people assume that someone is checking what’s on the market. The ingredients in my shampoo? The ingredients in my child’s toys? No one’s on the job? And that’s the answer: By and large, no one’s on the job,” says Daryl Ditz, a senior policy adviser at the Center for International Environmental Law (CIEL) in Washington, D.C.

“If we’re going to continue on as an industrial society that’s based on synthetic chemicals, we’ve got to figure out a way around this stuff. There’s really no question about that,” says Jody Roberts, an environmental policy expert at the Chemical Heritage Foundation in Philadelphia, Pa. “I think that’s where the frustration for some people is, that it needs to be happening faster.”

Related articles by Zemanta

- A Green Chemistry Primer: “Benign by Design” (worldchanging.com)

- California Attempts to Survey Unknown (Chemicals) (scientificamerican.com)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_b.png?x-id=008aff4d-39fc-45a1-9643-85ec3fd8e9ae)