Image courtesy of the researchers

Biochemical sensor implanted at initial biopsy could allow doctors to better monitor and adjust cancer treatments.

In the battle against cancer, which kills nearly 8 million people worldwide each year, doctors have in their arsenal many powerful weapons, including various forms of chemotherapy and radiation. What they lack, however, is good reconnaissance — a reliable way to obtain real-time data about how well a particular therapy is working for any given patient.

Magnetic resonance imaging and other scanning technologies can indicate the size of a tumor, while the most detailed information about how well a treatment is working comes from pathologists’ examinations of tissue taken in biopsies. Yet these methods offer only snapshots of tumor response, and the invasive nature of biopsies makes them a risky procedure that clinicians try to minimize.

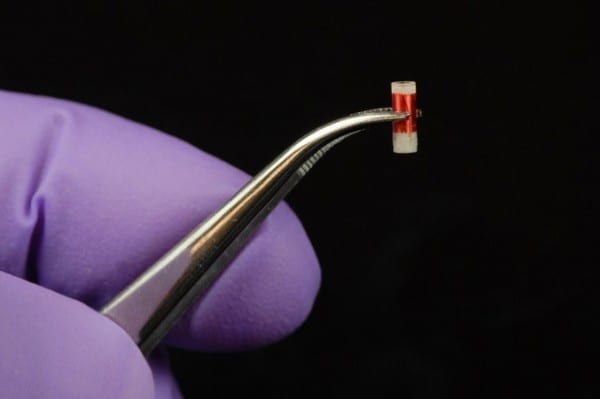

Now, researchers at MIT’s Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research are closing that information gap by developing a tiny biochemical sensor that can be implanted in cancerous tissue during the initial biopsy. The sensor then wirelessly sends data about telltale biomarkers to an external “reader” device, allowing doctors to better monitor a patient’s progress and adjust dosages or switch therapies accordingly. Making cancer treatments more targeted and precise would boost their efficacy while reducing patients’ exposure to serious side effects.

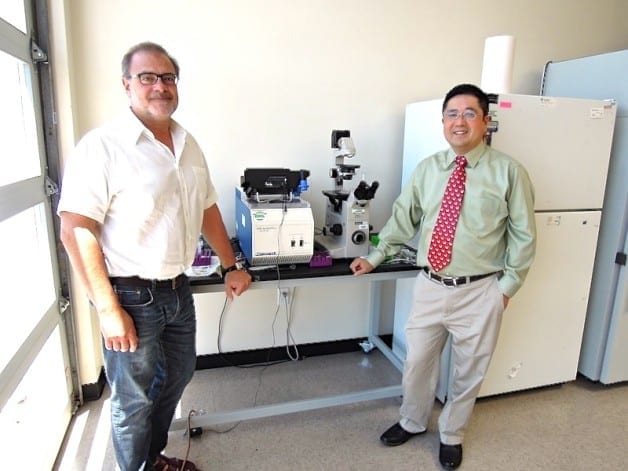

“We wanted to make a device that would give us a chemical signal about what’s happening in the tumor,” says Michael Cima, the David H. Koch (1962) Professor in Engineering in the Department of Materials Science and Engineering and a Koch Institute investigator who oversaw the sensor’s development. “Rather than waiting months to see if the tumor is shrinking, you could get an early read to see if you’re moving in the right direction.”

Two MIT doctoral students in Cima’s lab worked with him on the sensor project: Vincent Liu, now a postdoc at MIT, and Christophoros Vassiliou, now a postdoc at the University of California at Berkeley. Their research is featured in a paper in the journal Lab on a Chip that has been published online.

Measurements without MRI

The sensors developed by Cima’s team provide real-time, on-demand data concerning two biomarkers linked to a tumor’s response to treatment: pH and dissolved oxygen.

As Cima explains, when cancerous tissue is under assault from chemotherapy agents, it becomes more acidic. “Many times, you can see the response chemically before you see a tumor actually shrink,” Cima says. In fact, some therapies will trigger an immune system reaction, and the inflammation will make the tumor appear to be growing, even while the therapy is effective.

Oxygen levels, meanwhile, can help doctors gauge the proper dose of a therapy such as radiation, since tumors thrive in low-oxygen (hypoxic) conditions. “It turns out that the more hypoxic the tumor is, the more radiation you need,” Cima says. “So, these sensors, read over time, could let you see how hypoxia was changing in the tumor, so you could adjust the radiation accordingly.”

The sensor housing, made of a biocompatible plastic, is small enough to fit into the tip of a biopsy needle. It contains 10 microliters of chemical contrast agents typically used for magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and an on-board circuit to communicate with the external reader device.

Devising a power source for these sensors was critical, Cima explains. Four years ago, his team built a similar implantable sensor that could be read by an MRI scanner. “MRI scans are expensive and not easy to make part of routine care,” he says. “We wanted to take the next step and put some electronics on the device so we could take these measurements without an MRI.”

For power, these new sensors rely on the reader. Specifically, there’s a metal coil inside the reader and a much smaller coil in the sensor itself. An electric current magnetizes the coil inside the reader, and that magnetic field creates a voltage in the sensor’s coil when the two coils are close together — a process called mutual inductance. The reader sends out a series of pulses, and the sensor “rings back,” as Cima puts it. The variation in this return signal over time is interpreted by a computer to which the reader is wired, revealing changes in the targeted biomarkers.

Read more: Real-Time Data for Cancer Therapy

The Latest on: Biochemical sensor

[google_news title=”” keyword=”Biochemical sensor” num_posts=”10″ blurb_length=”0″ show_thumb=”left”]

via Google News

The Latest on: Biochemical sensor

- Copenhagen scientist develops optical magnetometer to spot flaws in MRI scans...on May 7, 2024 at 1:16 pm

A new invention hopes to eliminate this problem. A researcher from the Niels Bohr Institute and Danish Research Centre for Magnetic Resonance (DRCMR) has developed a sensor that uses laser light ...

- Sensors Bolster Army Prowesson May 2, 2024 at 5:00 pm

The Terrain Commander from Textron Corporation provides the basis for the U.S. Army's unattended ground sensor (UGS) Future Combat Systems. The sensor assembly is equipped with a variety of optical, ...

- Optical barcodes expand range of high-resolution sensoron April 26, 2024 at 11:27 am

The same geometric quirk that lets visitors murmur messages around the circular dome of the whispering gallery at St. Paul's Cathedral in London or across St. Louis Union Station's whispering arch ...

- Exercise-induced biochemical changes and their potential influence on cancer: a scientific reviewon April 25, 2024 at 10:19 pm

Aim To review and discuss the available international literature regarding the indirect and direct biochemical mechanisms that occur after exercise, which could positively, or negatively, influence ...

- Cyprus research centre spearheads medical diagnostics projecton April 24, 2024 at 11:01 pm

The Cyprus Research and Innovation Centre (CyRIC) recently announced that a groundbreaking lab-on-chip platform, named MultiLab, has been developed to meet the growing demand for small, versatile ...

- Optical microcavities empowered biochemical sensingon March 20, 2024 at 5:00 pm

Over the past decade, there have been significant advancements in optical microcavity-based biochemical sensors. These devices, noted for their high-quality factors, compact mode volumes ...

- Scientists create salt-sized sensor to unlock mind secrets wirelesslyon March 19, 2024 at 4:35 am

The sensor network is designed so that the chips ... real-time physiological information via noninvasive measurements of biochemical markers in biofluids, like sweat, tears, and saliva, so ...

- Sensors & Diagnostics editorial board memberson October 18, 2023 at 9:15 pm

Dr. Yetisen is an Associate Professor and Senior Lecturer in the Department of Chemical Engineering at Imperial College London, where he directs the Centre for Biochemical Sensors. He is passionate ...

- Biochemical changes as a result of prolonged strenuous exerciseon July 8, 2023 at 7:39 pm

Objective: To briefly review biochemical changes that may result from prolonged strenuous exercise and to relate these changes to health risk. Methods: Medline and Sports Discus databases were ...

- Physiological and Biochemical Zoology: Ecological and Evolutionary Approacheson September 20, 2022 at 8:59 pm

This title is part of a longer publication history. The full run of this journal will be searched. TITLE HISTORY A title history is the publication history of a journal and includes a listing of the ...

via Bing News