A handful of leftfield scientists have been trying to harness the power of gravity. Welcome to the world of Project Greenglow, writes Nic Young.

In science there exists a uniquely potent partnership between theory and engineering. It’s what’s given us atomic energy, the Large Hadron Collider and space-flight, to name a few of the more headline acts.

The theorists say: “This is theoretically possible.” The engineers then figure out how to make it work, confident the maths is correct and the theory stands up.

These camps are not mutually exclusive of course. Theorists understand engineering. Engineers draw on their deep understanding of the theory. It’s normally a pretty harmonious, if competitive, relationship.

Yet occasionally these two worlds collide. The theorists say something is just not possible and the engineers say: “We’re going to try it anyway – it’s worth a shot.”

There is one field of science where just such a contest has been raging for years, perhaps the most contentious field in all science/engineering – gravity control.

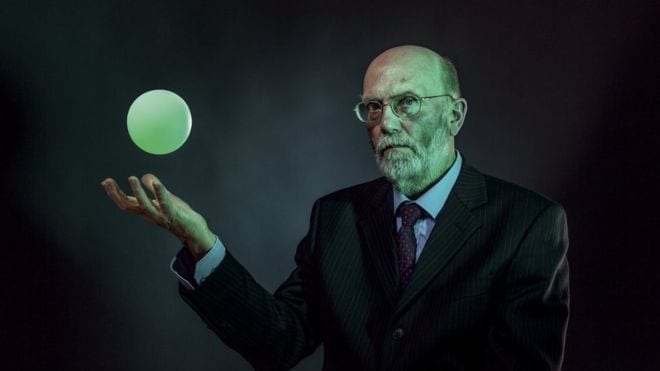

When, in the late 1980s, the aerospace engineer Dr Ron Evans went to his bosses at BAE Systems and asked if they’d let him attempt some form of gravity control, they should probably have offered him a cup of tea and a lie down. Gravity control was a notion beloved of science fiction writers that every respectable theoretical physicist said was impossible.

As Evans himself admits, it was a tough sell. “Let’s be clear – there were many people in the company who felt we shouldn’t do it because we made aeroplanes and this was highly speculative.” Pushing against gravity with wings and jets was BAE’s multi-billion pound business, why dabble in scientific heresy? Because, as Evans puts it: “The potential was absolutely enormous. It could totally change aerospace.”

If it was possible to make gravity push instead of pull, they would have a potentially infinite – and free – source of propulsion. It would put BAE Systems at the forefront of the greatest technological breakthrough since the invention of powered flight. It might just be worth a small punt.

They asked Evans to go away, consult with his colleagues and come up with some concepts. He brought them a drawing of a vertical take-off plane, powered by an as-yet non-existent “gravity engine”.

He worried it didn’t look visionary enough, so he asked the artist to add some green rays emanating from the plane – a green glow. When Evans’s bosses decided to give him a small budget and an office, Project Greenglow was born. “It was incredible, everyone was captivated by what we were trying to do. We were overwhelmed.”

Evans soon discovered he was able to call on engineers at leading UK universities to help with the research, and it wasn’t just academic curiosity. Like BAE, everyone was looking for the next propulsion paradigm. Wings and jets had reached their limits.

In the US, Nasa aerospace engineer Marc Millis began a parallel project – the Breakthrough Physics Propulsion Program. Nasa had committed to getting beyond the solar system within a generation, but knew conventional rockets would never get them there.

Learn more: Project Greenglow and the battle with gravity

The Latest on: Gravity control

[google_news title=”” keyword=”Gravity control” num_posts=”10″ blurb_length=”0″ show_thumb=”left”]

via Google News

The Latest on: Gravity control

- Cowboys NFL Draft grades 2024: Dallas uses nearly every pick to revamp offensive line, front sevenon April 27, 2024 at 4:27 pm

Dallas turned its trade back five spots in the first round on Thursday from 24 to 29 with the Detroit Lions into two new offensive linemen: Oklahoma offensive tackle Tyler Guyton (29th) and Kansas ...

- 5 things to know about Boston College’s Christian Mahogany, the Lions’ sixth-round pickon April 27, 2024 at 4:15 pm

The Detroit Lions concluded their 2024 NFL draft by adding another piece to their offensive line. With the 210th overall pick, the Lions selected Boston College’s Christian Mahogany. He’s the second ...

- Auburn DL Marcus Harris drafted No. 247 overall to the Houston Texanson April 27, 2024 at 3:57 pm

Multi-year starter on the defensive line for Auburn, Marcus Harris, has been drafted in the 7th round by the Houston Texans. Harris is the 247th overall pick in the 2024 NFL Draft. As a recruit On3 ...

- Wilmore Coaster Car Derby brings community togetheron April 27, 2024 at 2:57 pm

A downhill drag race descended on Jessamine County on Saturday as the Wilmore Coaster Car Derby occupied both lanes of Main Street.

- Gazelle Eclipse C380+ HMB review: Pricey but a solid choice for serious commuterson April 27, 2024 at 10:47 am

The Gazelle Eclipse C380+ HMB electric bicycle is on the pricey side, but it's a solid choice for those looking to ditch their automobile.

- Israel’s F-16I Soufa Fighter was Built for One Reason Onlyon April 27, 2024 at 7:49 am

Summary: The Israeli Air Force's F-16I Soufa, specifically enhanced for strategic operations, reflects Israel's advanced military capabilities, particularly in terms of nuclear warfare. Known as ...

- Review: Gravity and tension in ‘Joe Turner’s Come and Gone’ at Goodman Theatreon April 27, 2024 at 4:00 am

Director Chuck Smith leans into the darkness of August Wilson’s drama, set in a boarding house in the early 20th century.

- The best dehumidifiers to keep you dry and breathing easyon April 26, 2024 at 11:18 pm

Too much humidity in your home can lead to health problems. Check out the best dehumidifiers and discover why buying one is a wise investment for your home.

- Lucid Gravity’s Derek Jenkins On What Inspired This Luxe Electric SUVon April 26, 2024 at 9:22 am

Space for adults, even in the third row, lots of glass and architecture-inspired elements make this uber-powered, long range driving SUV a true luxury ...

- How Mark Zuckerberg is reimagining the classroomon April 15, 2024 at 3:00 am

Imagine hopping on a school bus and being transported to an immersive, educational tour of the inside of the human body — and no, not on a fictional episode of “The Magic School Bus.” This is the kind ...

via Bing News