Princeton University engineers have developed a new laser sensing technology that is expected to enable the remote distant detection of explosives, airborne pollutants and greenhouse gasses.

The technique differs from previous remote laser-sensing methods in that the returning beam is not just a reflection or scattering of the outgoing beam but an entirely new laser beam generated by oxygen atoms whose electrons have been “excited” to high energy levels. This “air laser” is a much more powerful tool than previously existed for remote measurements of trace amounts of chemicals in the air.

“We are able to send a laser pulse out and get another pulse back from the air itself,” said Richard Miles, a professor of mechanical and aerospace engineering at Princeton, the research group leader and co-author on the paper. “The returning beam interacts with the molecules in the air and carries their finger prints.”

The researchers, whose work is funded by the Office of Naval Research’s basic research program on Sciences Addressing Asymmetric Explosive Threats, published their new method Jan. 28 in the journal Science.

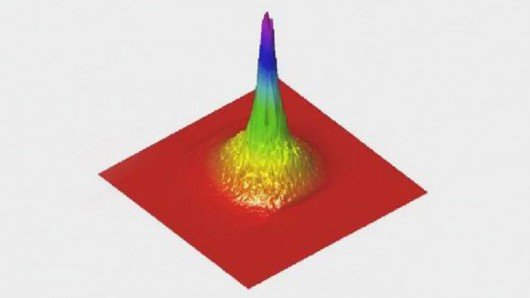

Miles collaborated with three other researchers: Arthur Dogariu, the lead author on the paper, and James Michael of Princeton, and Marlan Scully, a professor with joint appointments at Princeton and Texas A&M University. The new laser sensing method uses an ultraviolet laser pulse that is focused on a tiny patch of air, similar to the way a magnifying glass focuses sunlight into a hot spot. Within this hot spot – a cylinder-shaped region just 1 millimeter long – oxygen atoms become “excited” as their electrons get pumped up to high energy levels.

When the pulse ends, the electrons fall back down and emit infrared light. Some of this light travels along the length of the excited cylinder region and, as it does so, it stimulates more electrons to fall, amplifying and organizing the light into a coherent laser beam aimed right back at the original laser.

Researchers plan to use a sensor to receive the returning beam and determine what contaminants it encountered on the way back.

“In general, when you want to determine if there are contaminants in the air you need to collect a sample of that air and test it,” Miles said. “But with remote sensing you don’t need to do that. If there’s a bomb buried on the road ahead of you, you’d like to detect it by sampling the surrounding air, much like bomb-sniffing dogs can do, except from far away. That way you’re out of the blast zone if it explodes. It’s the same thing with hazardous gases – you don’t want to be there yourself. Greenhouse gases and pollutants are up in the atmosphere, so sampling is difficult.”