- Image via Wikipedia

It is already possible to send electricity without wires. Can devices be powered using ambient radiation from existing broadcasts?

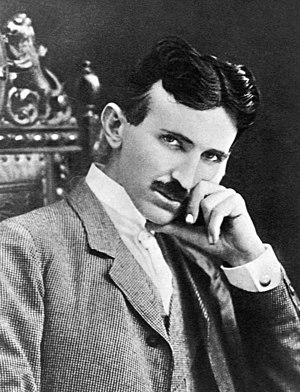

ANYONE whose mobile phone has ever run out of juice—which means, these days, more than half the world’s population—will like the idea of getting electrical power out of the air. The notion is far from new. A little over a century ago, the inventor Nikola Tesla drew up ambitious plans to transmit electrical power without wires. He carried out a series of experiments in which electric lights were illuminated via electrostatic induction, by connecting them to metal sheets suspended in a strong electric field produced by a distant transmitter. In 1898 he proposed a “world system” of giant towers that would form both a global wireless communications network and a means of delivering electricity over large areas without wires.

The construction of the first such tower, the Wardenclyffe Tower, on Long Island, began in 1901. Tesla’s backers included the financier J.P. Morgan, who invested $150,000. But before the tower was completed, Morgan and the other backers pulled out. They worried that the delivery of electricity through the air could not be metered, and there would be nothing to stop people from helping themselves.

But has Tesla had the last laugh after all? Today several firms—including Fulton Innovation, eCoupled, WiTricity and Powercast—are pursuing various technologies that deliver electrical power without wires (though over shorter distances than Tesla had in mind). WiTricity has demonstrated the ability to send enough energy across a room to run a flat-screen television using its approach, called “resonant magnetic coupling”. This is different from Tesla’s approach, but the firm’s founders have acknowledged his pioneering work.

In the long run, however, it may be Morgan who is vindicated, as researchers find ways to pull power out of the air without paying for it—a technique known as “energy scavenging” or “energy harvesting”. It is already possible to power small electronic devices, such as wireless sensors installed in buildings and industrial machinery, using a dedicated microwave transmitter nearby. The sensors pick up the microwaves with an antenna and convert the signal into electrical energy. But as power requirements drop and energy-scavenging technology improves, it will become increasingly practical to power these and other devices using just “ambient” energy—the sea of existing radio waves produced by television, radio and mobile-phone transmitters.

It sounds too good to be true. “There is something magical about it,” says Joshua Smith, a principal engineer at Intel’s research centre in Seattle.

Related articles by Zemanta

- Wire-free power (news.bbc.co.uk)

- Up in the Air (spectrum.ieee.org)