Interorbital offers CubeSat berths for $10,000 a pop.

MANY a youngster, Babbage included, has dreamed of going into space. But becoming an astronaut is a hard slog. Sandy Antunes suggests a less daunting proxy. An astrophysicist and programmer with decades of NASA experience, Dr Antunes is a proponent of picosatellites, and has just published the second of four books on “do-it-yourself” satellites. These tiny birds weigh around a kilogram and are shot up in lieu of ballast or in empty nooks and crannies on full-blown satellite launch missions. They are becoming so popular that 2013 may see the first dedicated launches.

This popularity owes much to two unrelated trends: the “maker” movement in electronics and the rise of smartphones. The maker movement brings open-source fervour to hardware, and in particular to devices other than computers, such as instruments and robots, often using the Arduino platform. This reduces the expertise needed to create circuit boards and program a functional system, whether it is terrestrial or winds up in orbit.

On the other end of the complexity spectrum, smartphone makers’ insistence on the tiniest and cheapest cameras, miniaturised sensors (like accelerometers and barometers) and specialised chips has made instruments suitable for picosatellite use as well, where size, power drain and weight are critically important. (In America, a firm needs a licence to put a camera in orbit, but that is the only significant regulatory hurdle.)

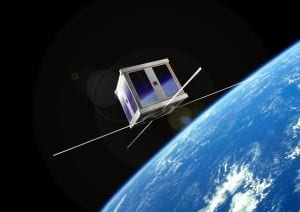

Since this newspaper described the potential of picosatellites in 2000, rocket firms have also become keener on ferrying them into space. That is mainly because standard formats have emerged, making them a less risky proposition for commercial launches. The most popular, CubeSat, was devised by California Polytechnic State University and Stanford University. It is a cube 10cm on a side, with standard electrical, physical and launch parameters.

A CubeSat may be tiny, but it packs a punch: biological experiments, earthquake sensors and propulsion tests have all been fielded using one. After being ejected, a CubeSat might unfurl antennas or a solar sail. Some designers hope to launch multiple units that then connect physically or wirelessly in space. In all, about 80 have been shoved towards low-earth orbit (LEO), and 50 or so have succeeded in orbiting and communicating with Earth. (A single launch failure in 2006 accounts for half of those lost.) Objects sent into LEO have self-decaying orbits that send them after weeks or months hurtling through the atmosphere to burn up before impact.

Dr Antunes says these satellites can be relatively affordable to build. He has ploughed about $7,000 in parts and testing kit into his Project Calliope, which will measure the ionosphere’s light, magnetic and electric fields, and beam the data back to Earth in the form of digital sound instrument (MIDI) codes. However, he and other early adopters have learned enough (and shared this wisdom) to drop the cost for future builders. Dr Antunes’s students at Capitol College, an engineering and technology school in Maryland, are designing their own CubeSat missions for as little as a few thousand dollars plus launch costs. And those launch costs remain the sticking point.

via The Economist – Babbage

The Latest Streaming News: Picosatellites updated minute-by-minute

Bookmark this page and come back often

Latest NEWS

Latest VIDEO