NO NEED FOR COLOR CORRECTION—HARVARD PHYSICISTS’ FLAT OPTICS, USING NANOTECHNOLOGY, GETS IT RIGHT THE FIRST TIME

Most lenses are, by definition, curved. After all, they are named for their resemblance to lentils, and a glass lens made flat is just a window with no special powers.

But a new type of lens created at the Harvard School of Engineering and Applied Sciences(SEAS) turns conventional optics on its head.

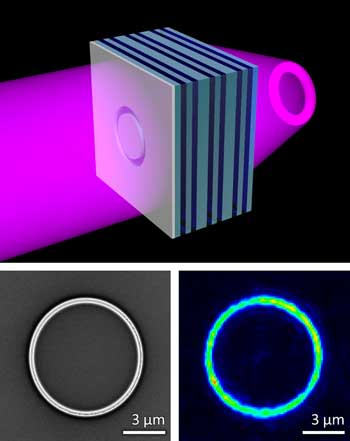

A major leap forward from a prototype device demonstrated in 2012, it is an ultra-thin, completely flat optical component made of a glass substrate and tiny, light-concentrating silicon antennas. Light shining on it bends instantaneously, rather than gradually, while passing through. The bending effects can be designed in advance, by an algorithm, and fine-tuned to fit almost any purpose.

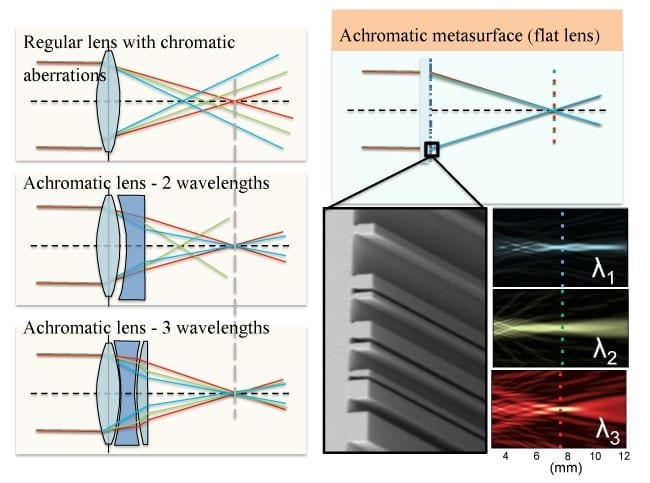

With this new invention described today in Science, the Harvard research team has overcome an inherent drawback of a wafer-thin lens: light at different wavelengths (i.e., colors) responds to the surface very differently. Until now, this phenomenon has prevented planar optics from being used with broadband light. Now, instead of treating all wavelengths equally, the researchers have devised a flat lens with antennas that compensate for the wavelength differences and produce a consistent effect—for example, deflecting three beams of different colors by the same angle, or focusing those colors on a single spot.

“What this now means is that complicated effects like color correction, which in a conventional optical system would require light to pass through several thick lenses in sequence, can be achieved in one extremely thin, miniaturized device,” said principal investigator Federico Capasso, the Robert L. Wallace Professor of Applied Physics and Vinton Hayes Senior Research Fellow in Electrical Engineering at Harvard SEAS.

Bernard Kress, Principal Optical Architect at Google [X], who was not involved in the research, hailed the advance:

“Google [X], and especially the Google Glass group, is relying heavily on state-of-the-art optical technologies to develop products that have higher functionalities, are easier to mass produce, have a smaller footprint, and are lighter, without compromising efficiency,” he said. “Last year, we challenged Professor Capasso’s group to work towards a goal which was until now unreachable by flat optics. While there are many ways to design achromatic optics, there was until now no solution to implement a dispersionless flat optical element which at the same time had uniform efficiency and the same diffraction angle for three separate wavelengths. We are very happy that Professor Capasso did accept the challenge, and also were very surprised to learn that his group actually solved that challenge within one year.”

Read more: Perfect colors, captured with one ultra-thin lens

The Latest on: Ultra-thin optics

[google_news title=”” keyword=”Ultra-thin optics” num_posts=”10″ blurb_length=”0″ show_thumb=”left”]

via Google News

The Latest on: Ultra-thin optics

- The Best Things at Le French Aren’t French at Allon April 30, 2024 at 9:56 pm

While the namesake fare at the restaurant’s newest location in 9&CO can hit or miss, the West African dishes are always delicious.

- Beats Solo 4 review: a slew of upgrades keep this fan favorite currenton April 30, 2024 at 7:00 am

Beats takes its wildly popular Solo on-ear wireless headphones to the next level with spatial and lossless audio.

- Samsung Galaxy Unpacked July 2024: Expected Announcements From Galaxy Z Fold 6 To Galaxy Ringon April 30, 2024 at 3:53 am

Samsung is expected to launch loads of new hardware at its Galaxy Unpacked event that’s likely scheduled for July 2024.

- M4 iPad Pro and more: What is Apple likely to announce next week?on April 30, 2024 at 1:08 am

Apple is staging its Let Loose event next week and what started as a likely iPad and accessories reveal now has a boatload of new rumours attached from M4 iPad Pros to a worldwide Vision Pro launch.

- I Tried Brooks’ New Hyperion Elite 4 Shoes & Felt Faster Than I Have in Yearson April 29, 2024 at 9:41 am

Running shoes these days have thick soles and prominent rockers. It’s like trying to run with a bean bag strapped to each foot: too much shoe for my liking. As someone who grew up in the minimalist ...

- New 2D material manipulates light with remarkable precision and minimal losson April 22, 2024 at 10:00 am

Responding to the increasing demand for efficient, tunable optical materials capable of precise light modulation to create greater bandwidth in communication networks and advanced optical systems, a ...

- Study shows ultra-thin two-dimensional materials can rotate the polarization of visible lighton April 22, 2024 at 8:52 am

It has been known for centuries that light exhibits wave-like behavior in certain situations. Some materials are able to rotate the polarization, i.e. the direction of oscillation, of the light wave ...

- I reviewed the Samsung Galaxy A55. It didn’t go as expectedon April 22, 2024 at 8:00 am

My time with the Samsung Galaxy A55 didn't get off to the best start and I worried about it. Did things change for the better? Here's the whole story.

- From new Xbox games to AR glasses, here are my favorite things I saw at my very first GDCon April 21, 2024 at 9:01 am

GDC 2024 is the first time I've ever been able to attend (this or any other major convention), and it was an unforgettable experience. I've written extensively around GDC since I came home, but I ...

- Xiaomi 14 Ultra’s new photography kit addition makes it feel like a compact camera, so what?on April 15, 2024 at 7:20 pm

We review the Xiaomi 14 Ultra photography kit on its performance, camera, and image quality as a compact camera. Is it worth the price?

via Bing News