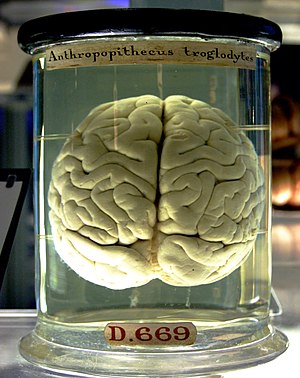

- Image via Wikipedia

New research holds promise for a noninvasive brain-computer interface that allows mental control over computers and prosthetics

Our bodies are wired to move, and damaged wiring is often impossible to repair. Strokes and spinal cord injuries can quickly disconnect parts of the brain that initiate movement with the nerves and muscles that execute it, and neurodegenerative disorders such as Parkinson’s disease and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) draw the process out to the same effect. Scientists have been looking for a way to bypass damaged nerves by directly connecting the brain to an assistive device—like a robotic limb—through brain-computer interface (BCI) technology. Now, researchers have demonstrated the ability to nonintrusively record neural signals outside the skull and decode them into information that could be used to move a prosthetic.

Past efforts at a BCI to animate an artificial limb involved electrodes inserted directly into the brain. The surgery required to implant the probes and the possibility that implants might not stay in place made this approach risky.

The alternative—recording neural signals from outside the brain—has its own set of challenges. “It has been thought for quite some time that it wasn’t possible to extract information about human movement using electroencephalography,” or EEG, says neuroscientist and electrical engineer Jose Contreras-Vidal. In trying to record the brain’s electrical activity off the scalp, he adds, “people assumed that the signal-to-noise ratio and the information content of these signals were limited.”

Evidently, that is not the case. In the March issue of The Journal of Neuroscience, Contreras-Vidal and his team from the bioengineering and kinesiology departments at the University of Maryland, College Park, show that the noisy brain waves recorded using noninvasive EEG can be mathematically decoded into meaningful information about complex human movements. “This means we can use a noninvasive method to develop the next generation of brain–computer interface machines,” Contreras-Vidal says. “It can expand considerably the range of clinical and rehabilitative applications.”

Related articles by Zemanta

- No Implants Needed: Movement-Generating Brain Waves Detected and Decoded Outside the Head (scienceblog.com)

- Mind-controlled prosthetics without brain surgery (newscientist.com)

- Good vibrations aid mind-controlled steering (newscientist.com)

- Brain computer interface on parade at CeBIT (ubergizmo.com)

- Mind Control, Biometric Passwords Could Change the World (usnews.com)