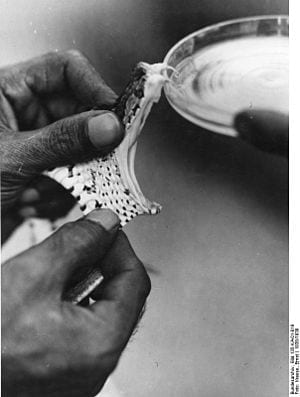

Administering antiparalytics topically via a nasal spray

A team of researchers led by Dr. Matt Lewin of the California Academy of Sciences, in collaboration with the Department of Anesthesia at the University of California, San Francisco, has pioneered a novel approach to treating venomous snakebites — administering antiparalytics topically via a nasal spray. This new, needle-free treatment may dramatically reduce the number of global snakebite fatalities, currently estimated to be as high as 125,000 per year.

The team demonstrated the success of the new treatment during a recent experiment conducted at UCSF; their results have been published in the medical journal Clinical Case Reports.

Snakebite is one of the most neglected of tropical diseases — the number of fatalities is comparable to that of AIDS in some developing countries. It has been estimated that 75% of snakebite victims who die do so before they ever reach the hospital, predominantly because there is no easy way to treat them in the field. Antivenoms provide an imperfect solution for a number of reasons — even if the snake has been identified and the corresponding antivenom exists, venomous bites often occur in remote locations far from population centers, and antivenoms are expensive, require refrigeration, and demand significant expertise to administer and manage.

“In addition to being an occupational hazard for field scientists, snakebite is a leading cause of accidental death in the developing world, especially among otherwise healthy young people,” says Lewin, the Director of the Center for Exploration and Travel Health at the California Academy of Sciences. “We are trying to change the way people think about this ancient scourge and persistent modern tragedy by developing an inexpensive, heat-stable, easy-to-use treatment that will at least buy people enough time to get to the hospital for further treatment.”

In his role as Director of the Academy’s Center for Exploration and Travel Health, Lewin prepares field medicine kits for the museum’s scientific expeditions around the world and often accompanies scientists as the expedition doctor. In 2011, Lewin put together snakebite treatment kits for the Academy’s Hearst Philippine Biodiversity Expedition, which would have required scientists to inject themselves if they needed treatment. When he saw their apprehension about the protocol, Lewin began to wonder if there might be an easier way to treat snakebite in the field.

In some fatal snakebites, victims are paralyzed by the snake’s neurotoxins, resulting in death by respiratory failure. A group of common drugs called anticholinesterases have been used for decades to reverse chemically-induced paralysis in operating rooms and, in intravenous form, to treat snakebite when antivenoms are not available or not effective. However, it is difficult to administer intravenous drugs to treat snakebite outside of a hospital, so Lewin began to explore the idea of a different delivery vehicle for these antiparalytics — a nasal spray.

In early April of 2013, Lewin and a team of anesthesiologists, led by Dr. Philip Bickler at UCSF Medical Center, designed and completed a complex experiment that took place at the medical center. During the experiment, a healthy human volunteer was paralyzed, while awake, using a toxin that mimics that of cobras and other snakes that disable their victims by paralysis. The experimental paralysis mimicked the effects of neurotoxic snakebite, progressing from eye muscle weakness all the way to respiratory difficulty, in the same order as is usually seen in envenomation. The team then administered the nasal spray and within 20 minutes the patient had recovered. The results of this experiment were published online in the medical journal, Clinical Case Reports.

The Latest Bing News on:

Venomous Snakebites

- Snakebite alert; 9,900 cases recorded annuallyon April 27, 2024 at 7:11 am

The country recorded 59,600 snakebite cases between 2015 and 2020, the first time such data has been put together.

- Dog Gets Bitten in the Face to Save His Owner From a Venomous Snakeon April 27, 2024 at 5:47 am

A dog from Colorado Springs is being called a hero after stepping between his owner and a rattlesnake, saving her from a venomous bite.

- Snakes and Lizards Are Locked in an Epic Evolutionary Battleon April 26, 2024 at 9:39 am

"Most large varanids or monitor lizards that prey on venomous snakes have inherited neurotoxin resistance," researcher Bryan Fry said.

- What to do if a venomous rattlesnake bites you and you don’t have cell service in Idahoon April 25, 2024 at 2:30 am

Call 911 if you have an emergency, like a rattlesnake bite. Remember, you don’t need a cell phone provider to use emergency services. Worst case scenario, you find yourself in a remote area with no ...

- Wildlife Center of Virginia treats Copperhead Snakeon April 24, 2024 at 7:55 pm

WAYNESBORO, Va. (WHSV) -The Wildlife Center of Virginia recently treated a Copperhead Snake, which is a venomous snake.

- Hospital begs for snakebite victims to stop bringing in serpents when seeking help: 'Puts the staff at risk'on April 23, 2024 at 12:26 pm

Australian health authorities have asked for victims of snakebites to stop trying to interact with the potentially venomous creatures more than they already have.

- Don’t bring us the snake that bit you, Australian hospital sayson April 23, 2024 at 10:43 am

After any snake bite, Australian health officials say victims should immediately seek medical care; but trying to catch, kill, or photograph the snake after a bite “just puts people at risk,” said Dr.

- A hospital in Australia is begging snakebite victims to stop bringing the snakes in with themon April 23, 2024 at 3:27 am

Snakebite victims in Australia are being advised not to bring the snakes to the emergency room, following a scare at a Queensland hospital this month.

- Medical Workers Ask Venomous Snake Bite Victims to Stop Bringing Snakes to the Hospitalon April 22, 2024 at 2:09 pm

Medical workers in Australia are asking snake bite victims to stop bringing snakes to the hospital, after several snake bite sufferers brought venomous reptiles to the emergency room this year ...

- Venomous snakes are awaking in Idaho. Here’s how much antivenom will cost if you’re bittenon April 19, 2024 at 3:00 am

The minimum treatment for a snake bite is 10 vials of antivenom and the cost of each vial is in the four digits.

The Latest Google Headlines on:

Venomous Snakebites

[google_news title=”” keyword=”Venomous Snakebites” num_posts=”10″ blurb_length=”0″ show_thumb=”left”]

The Latest Bing News on:

Anti paralytics for snakebites

- Hospital urges snakebite victims to refrain from bringing in serpentson April 23, 2024 at 4:00 pm

An Australian hospital urged snakebite victims to stop trying to catch the slithery culprits when seeking medical attention after one patient came in carrying a serpent in a loosely locked box.

- Hospital begs for snakebite victims to stop bringing in serpents when seeking help: 'Puts the staff at risk'on April 23, 2024 at 12:26 pm

Australian health authorities have asked for victims of snakebites to stop trying to interact with the potentially venomous creatures more than they already have.

- A hospital in Australia is begging snakebite victims to stop bringing the snakes in with themon April 23, 2024 at 3:27 am

Snakebite victims in Australia are being advised not to bring the snakes to the emergency room, following a scare at a Queensland hospital this month.

- Tips to keep your dog safe from rattlesnake biteson April 22, 2024 at 9:06 am

Veterinarians are asking pet owners to keep their dogs on a leash and be alert of rattlesnakes as temperatures start to heat up.

- Snakebite Lands Vacationer in Intensive Care for Four Dayson April 16, 2024 at 11:13 am

The blunt-nosed viper bit the woman while she was about to step onto a meditation platform at her hotel, causing immediate pain.

The Latest Google Headlines on:

Anti paralytics for snakebites

[google_news title=”” keyword=”anti paralytics for snakebites” num_posts=”10″ blurb_length=”0″ show_thumb=”left”]