via World Economic Forum

Many workers, in short, are losing the race against the machine

A faltering economy explains much of the job shortage in America, but advancing technology has sharply magnified the effect, more so than is generally understood, according to two researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

The automation of more and more work once done by humans is the central theme of “Race Against the Machine,” an e-book to be published on Monday.

“Many workers, in short, are losing the race against the machine,” the authors write.

Erik Brynjolfsson, an economist and director of the M.I.T. Center for Digital Business, and Andrew P. McAfee, associate director and principal research scientist at the center, are two of the nation’s leading experts on technology and productivity. The tone of alarm in their book is a departure for the pair, whose previous research has focused mainly on the benefits of advancing technology.

Indeed, they were originally going to write a book titled, “The Digital Frontier,” about the “cornucopia of innovation that is going on,” Mr. McAfee said. Yet as the employment picture failed to brighten in the last two years, the two changed course to examine technology’s role in the jobless recovery.

The authors are not the only ones recently to point to the job fallout from technology. In the current issue of the McKinsey Quarterly, W. Brian Arthur, an external professor at the Santa Fe Institute, warns that technology is quickly taking over service jobs, following the waves of automation of farm and factory work. “This last repository of jobs is shrinking — fewer of us in the future may have white-collar business process jobs — and we have a problem,” Mr. Arthur writes.

The M.I.T. authors’ claim that automation is accelerating is not shared by some economists. Prominent among them are Robert J. Gordon of Northwestern and Tyler Cowen of George Mason University, who contend that productivity improvement owing to technological innovation rose from 1995 to 2004, but has trailed off since. Mr. Cowen emphasized that point in an e-book, “The Great Stagnation,” published this year.

Technology has always displaced some work and jobs. Over the years, many experts have warned — mistakenly — that machines were gaining the upper hand. In 1930, the economist John Maynard Keynes warned of a “new disease” that he termed “technological unemployment,” the inability of the economy to create new jobs faster than jobs were lost to automation.

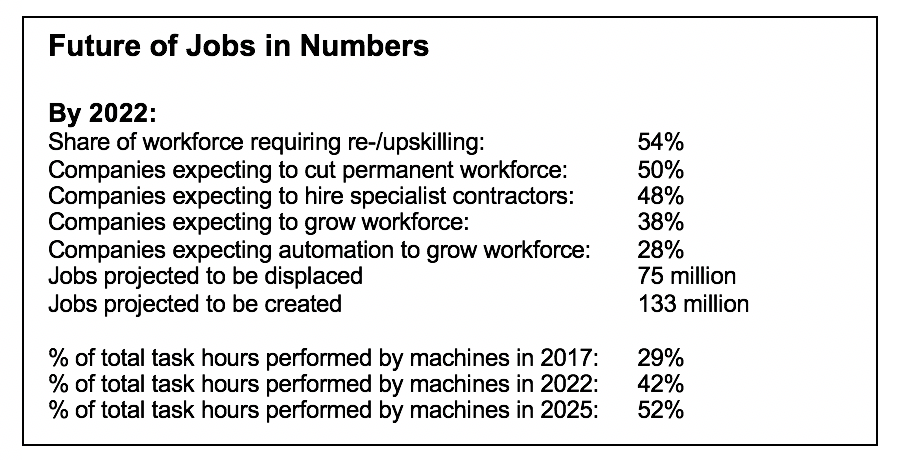

But Mr. Brynjolfsson and Mr. McAfee argue that the pace of automation has picked up in recent years because of a combination of technologies including robotics, numerically controlled machines, computerized inventory control, voice recognition and online commerce.

Faster, cheaper computers and increasingly clever software, the authors say, are giving machines capabilities that were once thought to be distinctively human, like understanding speech, translating from one language to another and recognizing patterns. So automation is rapidly moving beyond factories to jobs in call centers, marketing and sales — parts of the services sector, which provides most jobs in the economy.

During the last recession, the authors write, one in 12 people in sales lost their jobs, for example. And the downturn prompted many businesses to look harder at substituting technology for people, if possible. Since the end of the recession in June 2009, they note, corporate spending on equipment and software has increased by 26 percent, while payrolls have been flat.

Corporations are doing fine. The companies in the Standard & Poor’s 500-stock index are expected to report record profits this year, a total $927 billion, estimates FactSet Research. And the authors point out that corporate profit as a share of the economy is at a 50-year high.

Productivity growth in the last decade, at more than 2.5 percent, they observe, is higher than the 1970s, 1980s and even edges out the 1990s. Still the economy, they write, did not add to its total job count, the first time that has happened over a decade since the Depression.

The skills of machines, the authors write, will only improve. In 2004, two leading economists, Frank Levy and Richard J. Murnane, published “The New Division of Labor,” which analyzed the capabilities of computers and human workers. Truck driving was cited as an example of the kind of work computers could not handle, recognizing and reacting to moving objects in real time.

But last fall, Google announced that its robot-driven cars had logged thousands of miles on American roads with only an occasional assist from human back-seat drivers. The Google cars, Mr. Brynjolfsson said, are but one sign of the times.