New research is zeroing in on a biochemical basis for the placebo effect — possibly opening a Pandora’s box for Western medicine.

The Chain of Office of the Dutch city of Leiden is a broad and colorful ceremonial necklace that, draped around the shoulders of Mayor Henri Lenferink, lends a magisterial air to official proceedings in this ancient university town. But whatever gravitas it provided Lenferink as he welcomed a group of researchers to his city, he was quick to undercut it. “I am just a humble historian,” he told the 300 members of the Society for Interdisciplinary Placebo Studies who had gathered in Leiden’s ornate municipal concert hall, “so I don’t know anything about your topic.”

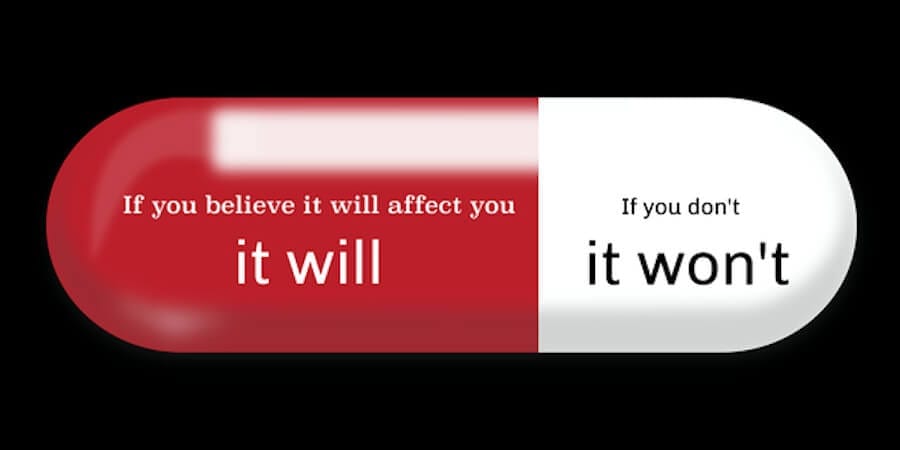

He was being a little disingenuous. He knew enough about the topic that these psychologists and neuroscientists and physicians and anthropologists and philosophers had come to his city to talk about — the placebo effect, the phenomenon whereby suffering people get better from treatments that have no discernible reason to work — to call it “fake medicine,” and to add that it probably works because “people like to be cheated.” He took a beat. “But in the end, I believe that honesty will prevail.”

Lenferink might not have been so glib had he attended the previous day’s meeting on the other side of town, at which two dozen of the leading lights of placebo science spent a preconference day agonizing over their reputation — as purveyors of sham medicine who prey on the desperate and, if they are lucky, fool people into feeling better — and strategizing about how to improve it. It’s an urgent subject for them, and only in part because, like all apostate professionals, they crave mainstream acceptance. More important, they are motivated by a conviction that the placebo is a powerful medical treatment that is ignored by doctors only at their patients’ expense.

And after a quarter-century of hard work, they have abundant evidence to prove it. Give people a sugar pill, they have shown, and those patients — especially if they have one of the chronic, stress-related conditions that register the strongest placebo effects and if the treatment is delivered by someone in whom they have confidence — will improve. Tell someone a normal milkshake is a diet beverage, and his gut will respond as if the drink were low fat. Take athletes to the top of the Alps, put them on exercise machines and hook them to an oxygen tank, and they will perform better than when they are breathing room air — even if room air is all that’s in the tank. Wake a patient from surgery and tell him you’ve done an arthroscopic repair, and his knee gets better even if all you did was knock him out and put a couple of incisions in his skin. Give a drug a fancy name, and it works better than if you don’t.

You don’t even have to deceive the patients. You can hand a patient with irritable bowel syndrome a sugar pill, identify it as such and tell her that sugar pills are known to be effective when used as placebos, and she will get better, especially if you take the time to deliver that message with warmth and close attention. Depression, back pain, chemotherapy-related malaise, migraine, post-traumatic stress disorder: The list of conditions that respond to placebos — as well as they do to drugs, with some patients — is long and growing.

But as ubiquitous as the phenomenon is, and as plentiful the studies that demonstrate it, the placebo effect has yet to become part of the doctor’s standard armamentarium — and not only because it has a reputation as “fake medicine” doled out by the unscrupulous to the credulous. It also has, so far, resisted a full understanding, its mechanisms shrouded in mystery. Without a clear knowledge of how it works, doctors can’t know when to deploy it, or how.

Not that the researchers are without explanations. But most of these have traditionally been psychological in nature, focusing on mechanisms like expectancy — the set of beliefs that a person brings into treatment — and the kind of conditioning that Ivan Pavlov first described more than a century ago. These theories, which posit that the mind acts upon the body to bring about physical responses, tend to strike doctors and researchers steeped in the scientific tradition as insufficiently scientific to lend credibility to the placebo effect. “What makes our research believable to doctors?” asks Ted Kaptchuk, head of Harvard Medical School’s Program in Placebo Studies and the Therapeutic Encounter. “It’s the molecules. They love that stuff.” As of now, there are no molecules for conditioning or expectancy — or, indeed, for Kaptchuk’s own pet theory, which holds that the placebo effect is a result of the complex conscious and nonconscious processes embedded in the practitioner-patient relationship — and without them, placebo researchers are hard-pressed to gain purchase in mainstream medicine.

Learn more: What if the Placebo Effect Isn’t a Trick?

The Latest on: Placebo effect

[google_news title=”” keyword=”placebo effect” num_posts=”10″ blurb_length=”0″ show_thumb=”left”]

via Google News

The Latest on: Placebo effect

- Researchers use postbiotic to ease acid reflux symptomson May 2, 2024 at 1:52 pm

Japanese researchers used a heat-killed lactic acid bacterium, defined as a postbiotic, to significantly improve one of the measures of symptoms of subjects suffering from acid reflux. A postbiotic ...

- Treatment of Antidepressant-Induced Sexual Dysfunctionon April 30, 2024 at 5:00 pm

Insofar as sexual function improvement may be responsive to placebo effects, it is impossible to estimate the true efficacy of these antidotes. [27] Most of these antidotes either have serotonin ...

- You’ve heard of the placebo effect – but what’s the nocebo effect? Is pain all in the mind?on April 29, 2024 at 4:23 pm

The beneficial effect’s negative cousin is garnering more attention as Australian researchers say ‘social contagion’ is possible ...

- The Power of the Placebo Effect: How Our Minds Can Heal Our Bodieson April 26, 2024 at 4:23 am

Power of the placebo effect! Where belief leads to real changes. How our minds influence our bodies and ways to harness this effect.

- Nocebo ― a placebo's evil twinon March 28, 2024 at 1:20 am

You've heard of the placebo effect: when positive thinking makes you believe your meds are working. Nocebo is the power of negative thinking. Wait, what? "Somebody tells you 'God, you look ...

- A Psychologist Explains The ‘Nocebo Effect’—And How To Avoid Iton December 10, 2023 at 10:14 am

Its ability to shape our health outcomes through belief alone is evident in the much celebrated placebo effect, one of the strongest testaments to the mind’s power. While much attention has been ...

- The placebo effect: powerful, powerless or redundant?on October 17, 2023 at 12:09 pm

george.org.au Over the last 200 years, the placebo effect has cast a large and persuasive shadow over the medical field. In that time it has been by turn; harmless charade, charlatan's ruse, ...

- New Study Looks At Ivermectin Versus Placebo To Treat Covid-19on October 25, 2022 at 12:08 pm

The placebo effect, whereby patients feel improvement in symptoms even when receiving a placebo, is an area of intense study. There is growing evidence that this effect is not ‘fake’, as ...

- Is the Nocebo Effect Hurting Your Health?on July 31, 2022 at 7:18 am

You’ve heard of the placebo effect, right? That's what occurs when patients think they’re getting a fancy new drug, but what they’re really getting is just a sugar pill. Then, in a case of ...

via Bing News