- Image via Wikipedia

The real and the digital worlds are converging, bringing much greater efficiency and lots of new opportunities, says Ludwig Siegele. But is it what people want?

WHAT if there were two worlds, the real one and its digital reflection?

The real one is strewn with sensors, picking up everything from movement to smell. The digital one, an edifice built of software, takes in all that information and automatically acts on it. If a door opens in the real world, so does its virtual equivalent. If the temperature in the room with the open door falls below a certain level, the digital world automatically turns on the heat.

This was the vision that David Gelernter, a professor of computer science at Yale University, put forward in his book “Mirror Worlds” in the early 1990s. “You will look into a computer screen and see reality,” he predicted. “Some part of your world—the town you live in, the company you work for, your school system, the city hospital—will hang there in a sharp colour image, abstract but recognisable, moving subtly in a thousand places.”

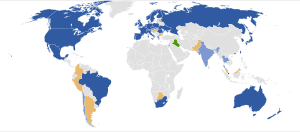

Even two decades later that sounds like science fiction. But this special report will argue that Mr Gelernter was surprisingly prescient: mankind is indeed building more and more “mirror worlds”, or “smart systems”, as they are often called. The real and the digital worlds are converging, thanks to a proliferation of connected sensors and cameras, ubiquitous wireless networks, communications standards and the activities of humans themselves.

This convergence may not be instantly discernible, because it is happening in many places at once and is often not understood for what it is. It is most advanced in controlled environments. For example, software developed by Siemens, a technology conglomerate, maintains virtual replicas of factories to monitor and reconfigure them. But it is spreading everywhere and has developed a language all of its own. Glen Allmendinger of Harbor Research, a consultancy, calls it the “virtualisation of the real world”. Researchers at MIT’s Media Lab who connect real-life objects with copies in Second Life, a virtual world, refer to the result as “cross reality”. Google’s Earth and Street View services are the first, if static, replicas of the entire world; sensors placed in cows allow the tracking of their every move from birth to abattoir; smart power meters tell utilities in real time how much electricity is used.

Yet it is the smartphone and its “apps” (small downloadable applications that run on these devices) that is speeding up the convergence of the physical and the digital worlds. Smartphones are packed with sensors, measuring everything from the user’s location to the ambient light. Much of that information is then pumped back into the network. Apps, for their part, are miniature versions of smart systems that allow users to do a great variety of things, from tracking their friends to controlling appliances in their homes.

Smartphones are also where the virtual and the real meet most directly and merge into something with yet another fancy name: “augmented reality”. Download an app called “Layar” onto your smartphone, turn on its video camera, point at a street, and the software will overlay the picture on the screen with all kinds of digital information, such as the names of the businesses on the street or if a house is for sale.