If starships are ever built, it will be in the far future. But that does not deter the intrepid band of scientists who are thinking about how to do it

SPACE, as Douglas Adams pointed out in “The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy”, is big. Really big. It is so big, in fact, that even science fiction struggles to make sense of it. Most sci-fi waves away the problem of the colossal distances between stars by appealing to magic, in the form of some kind of faster-than-light hyperdrive, hoping readers will forgive the nonsense in favour of enjoying a good story.

But there are scientists, engineers and science-fiction writers out there who like a challenge. On October 22nd a small but dedicated audience gathered at the Royal Astronomical Society (RAS) in London to hear some of them discuss the latest ideas about how interstellar travel might be made to work in the real world. The symposium was a follow-up to a larger shindig held earlier this year in San Diego.

Starship research is enjoying something of a boom. “A few years ago, there was only one organisation in the world working on interstellar travel,” Jim Benford, a microwave physicist and former fusion researcher, told the conference. “Now there are five.” The following day many of the speakers at the event would visit the British Interplanetary Society (BIS, the venerable organisation of which Dr Benford spoke) to discuss design details for a starship named Icarus.

Starship research has always been a small field, full of iconoclasts and dreamers fitting the activity around their “proper” jobs. Serious work in the field dates back to 1968, when Freeman Dyson, an independent-minded physicist, investigated the possibilities offered by rockets powered by a series of nuclear explosions. Then, in the 1970s, the BIS designed Daedalus, an unmanned vessel that would use a fusion rocket to attain 12% of the speed of light, allowing it to reach Barnard’s Star, six light-years away, in 50 years. That target, though not the nearest star to the sun, was the nearest then suspected of having at least one planet.

How final a frontier?

After Daedalus, interest flagged. Lately, though, several developments have given the field a shot in the arm.

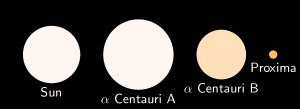

The internet has made it easier for like-minded dreamers to get in touch. Astronomers have discovered thousands of alien planets (including, possibly, one around Alpha Centauri B, which at 4.4 light-years away is part of the star system that actually is closest to the sun), and this exoplanet boom has caught the public’s imagination, as well as giving starship researchers a list of destinations. The rise of the private space industry, which aims to slash the cost of getting into orbit, brings hope that the sort of orbital infrastructure which would be needed to build a starship might one day be developed. And the involvement of DARPA, an arm of the American defence department, which is sponsoring a long-term project to develop the sorts of technology a starship might require, has brought money and attention.

The chief problem, as Adams noted, is distance. During the cold war America spent several years and much treasure (peaking in 1966 at 4.4% of government spending) to send two dozen astronauts to the Moon and back. But on astronomical scales, a trip to the Moon is nothing. If Earth—which is 12,742km, or 7,918 miles, across—were shrunk to the size of a sand grain and placed on the desk of The Economist’s science correspondent, the Moon would be a smaller sand grain about 3cm away. The sun would be a larger ball nearly 12 metres down the hall. And Alpha Centauri B would be around 3,200km distant, somewhere near Volgograd, in Russia.

Chemical rockets simply cannot generate enough energy to cross such distances in any sort of useful time. Voyager 1, a space probe launched in 1977 to study the outer solar system, has travelled farther from Earth than any other object ever built. A combination of chemical rocketry and gravitational kicks from the solar system’s planets have boosted its velocity to 17km a second. At that speed, it would (were it pointing in the right direction) take more than 75,000 years to reach Alpha Centauri.

Go deeper with Bing News on:

Interstellar travel

- 'God's Hand' interstellar cloud reaches for the stars in new Dark Energy Camera image (video)

Engaging articles, breathtaking images and expert knowledge ...

- Meet HELIX, the High-Altitude Balloon That May Solve a Deep Cosmic Mystery

Every now and then, tiny particles of antimatter strike Earth from cosmic parts unknown. A new balloon-borne experiment launching this spring may at last find their source ...

- Nasa engineers bring Voyager 1 back to life after interstellar glitch

After a sudden loss of contact in November, mission controllers were able to reestablish contact with the probe across 15bn miles of space ...

- Inside NASA's 5-month fight to save the Voyager 1 mission in interstellar space

After months of trying to reestablish communication with the Voyager 1 probe — the most distant human-made object in existence — NASA finally announced success.

- NASA re-establishes communication with Voyager 1 interstellar spacecraft that went silent for months

NASA re-established communication with Voyager 1, an interstellar spacecraft that nearly five months ago began sending unreadable data back to the space agency.

Go deeper with Google Headlines on:

Interstellar travel

[google_news title=”” keyword=”Interstellar travel” num_posts=”5″ blurb_length=”0″ show_thumb=”left”]

Go deeper with Bing News on:

Space travel

- Flips, floating, and the future of humanity: A Q&A from space with a Syracuse astronaut

NASA astronauts Jeanette Epps and Matthew Dominick spoke to Syracuse.com last Friday from the International Space Station orbiting 250 miles above Earth. During the interview, Epps and Dominick appeared standing side by side on a live video feed from the cramped interior of the ISS.

- Shhh! 3 Secret Space Stocks Flying Below Wall Street’s Radar

Stock Market News, Stock Advice & Trading Tips Outer space has inspired and captivated humans ever since we’ve been

Go deeper with Google Headlines on:

Space travel

[google_news title=”” keyword=”space travel” num_posts=”5″ blurb_length=”0″ show_thumb=”left”]