If 3-D printers are ever going to live up to their promise as the factories of the future, they’ll need to do more than just pop out plastic doodads.

MakerBots can churn out plastic Yoda heads all day long, but even relatively simple electromechanical constructions are still far beyond the capabilities of even the most advanced 3-D printers.

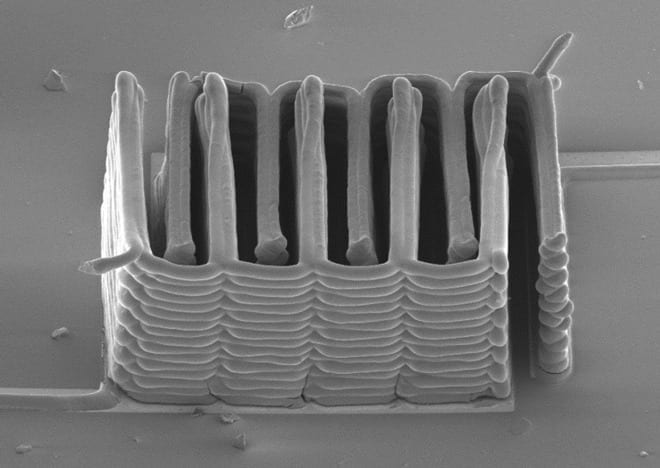

It turns out the challenge isn’t so much the machines, but rather what’s put into them. Professor Jennifer Lewis is the head of the Lewis Lab at Harvard and has spent the last couple decades working on a series of smart “inks” that allow designers to create bespoke batteries and electrical contacts using entry-level 3-D printers. “We’re focusing on expanding 3-D printing from form into function,” she says. With enough time and a little luck, designers will be able to 3-D print a robot and watch it walk itself out of the printer.

Ink doesn’t really do justice to the technical sophistication of Lewis’ materials. The battery material is solid under normal conditions, but liquifies under pressure before returning to its solid state. This novel property allows the batteries to be deposited on a plastic substrate at room temperature and opens up a world of design flexibility not available with traditional high-temperature manufacturing processes. In theory, instead of dedicating a prime piece of circuit board real estate to an off-the-shelf battery, Lewis’ liquid power source could be deposited in-between other components to help reduce the size of the gadgets.

One might expect these miraculous materials to be fabricated in some futuristic clean room, but they’re easily manufactured in Lewis’ relatively ordinary academic environment. The battery materials are produced by suspending nano-particles of lithium titanium oxide in a mixture of deionized water and ethylene glycol. Ceramic balls are added to the container holding the charged concoction and serve as agitators, breaking down the metal. The bottle is spun for 24 hours after which the balls are removed, the battery material is separated in a centrifuge, and designers are left with a fresh cartridge of wonder ink.

Custom syringes, with barrels just microns wide, can be included in a multi-head array of a RepRap style 3-D printer, allowing for the fabrication of relatively complex devices. For instance, one printhead could lay down a bed of plastic, another could deposit silver electrical traces, and a third could print buttons, crafting a crude game controller.

The Latest on: Printed Batteries

[google_news title=”” keyword=”Printed Batteries” num_posts=”10″ blurb_length=”0″ show_thumb=”left”]

via Google News

The Latest on: Printed Batteries

- Former Gaither High teacher arrested for sexual acts against student, deputies sayon May 10, 2024 at 10:33 am

A 46-year-old former Gaither High School art teacher was arrested Thursday after investigators determined he sexually battered a student at the school last year, deputies said.

- IDTechEx Explores Printed Electronics in Electrified and Autonomous Mobilityon May 10, 2024 at 8:52 am

Historically, printed electronics technologies have nurtured a close relationship with the automotive sector, with printed force sensors pioneering passenger safety through seat o ...

- Call2Recycle and Ascend Elements Formalize Agreement to Offer Customized EV Battery Management, Logistics and Recycling Serviceson May 8, 2024 at 1:18 am

A new agreement between Ascend Elements and Call2Recycle will bring customized electric vehicle (EV) battery management, logistics and recycling services ...

- Seat occupancy sensors and gaming – IDTechEx explores printed and flexible sensorson May 7, 2024 at 4:01 am

Battery health monitoring in electric vehicles using multi-functional hybrid sensors is an emerging role for printed and flexible sensors. Temperature and pressure sensors can be integrated together ...

- Best photo printers of 2024 - our top pickson May 3, 2024 at 11:44 am

While they aren't made for landscapes and large portraits, these snapshot printers are built for mobility, with battery power and easy printing from your smartphone. If it's photo printing on the ...

- $140 million lithium battery project bringing over 500 jobs to the Charlotte areaon May 2, 2024 at 9:27 am

The company’s new facility, its first in the U.S., will manufacture battery components for customers across North America.

- Battery chargers - what you need to knowon April 30, 2024 at 5:00 pm

Different capacities of rechargeable batteries (indicated in mAh or milliamp hours, printed on the packaging) shouldn’t be charged together. This is because smaller cells could be overcharged and ...

- Battery Cyclers Market worth $1,609 million by 2029 - Exclusive Report by MarketsandMarkets™on April 30, 2024 at 7:26 am

The global battery cyclers market size is projected to grow from USD 794 million in 2024 to USD 1,609 million by 2029 at CAGR of 15.2% during the forecast period according to a new report by ...

- Sakuu’s Dry Printed and UN38.3 Certified Li-Metal Batteries Hit 1,000 Cycle Milestoneon April 29, 2024 at 5:00 am

Sakuu® has manufactured its high-energy, high-power Li-Metal Cypress battery cell using a fully dry manufacturing process.

- Sakuu’s Dry Printed and UN38.3 Certified Li-Metal Batteries Hit 1,000 Cycle Milestoneon April 28, 2024 at 5:00 pm

“Manufacturing Cypress in a fully dry process with the Kavian platform is a key step in enabling high-quality solid-state batteries to be produced in high volume in the future. Leveraging dry printing ...

via Bing News