Image courtesy of Nasim Hyder and Nisarg J. Shah

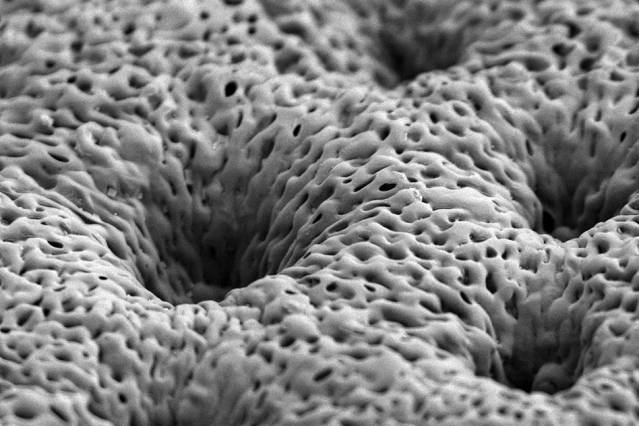

Coated tissue scaffolds help the body grow new bone to repair injuries or congenital defects.

MIT chemical engineers have devised a new implantable tissue scaffold coated with bone growth factors that are released slowly over a few weeks. When applied to bone injuries or defects, this coated scaffold induces the body to rapidly form new bone that looks and behaves just like the original tissue.

This type of coated scaffold could offer a dramatic improvement over the current standard for treating bone injuries, which involves transplanting bone from another part of the patient’s body — a painful process that does not always supply enough bone. Patients with severe bone injuries, such as soldiers wounded in battle; people who suffer from congenital bone defects, such as craniomaxillofacial disorders; and patients in need of bone augmentation prior to insertion of dental implants could benefit from the new tissue scaffold, the researchers say.

“It’s been a truly challenging medical problem, and we have tried to provide one way to address that problem,” says Nisarg Shah, a recent PhD recipient and lead author of the paper, which appears in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences this week.

Paula Hammond, the David H. Koch Professor in Engineering and a member of MIT’s Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research and Department of Chemical Engineering, is the paper’s senior author. Other authors are postdocs M. Nasim Hyder and Mohiuddin Quadir, graduate student Noémie-Manuelle Dorval Courchesne, Howard Seeherman of Restituo, Myron Nevins of the Harvard School of Dental Medicine, and Myron Spector of Brigham and Women’s Hospital.

Stimulating bone growth

Two of the most important bone growth factors are platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) and bone morphogenetic protein 2 (BMP-2). As part of the natural wound-healing cascade, PDGF is one of the first factors released immediately following a bone injury, such as a fracture. After PDGF appears, other factors, including BMP-2, help to create the right environment for bone regeneration by recruiting cells that can produce bone and forming a supportive structure, including blood vessels.

Efforts to treat bone injury with these growth factors have been hindered by the inability to effectively deliver them in a controlled manner. When very large quantities of growth factors are delivered too quickly, they are rapidly cleared from the treatment site — so they have reduced impact on tissue repair, and can also induce unwanted side effects.

“You want the growth factor to be released very slowly and with nanogram or microgram quantities, not milligram quantities,” Hammond says. “You want to recruit these native adult stem cells we have in our bone marrow to go to the site of injury and then generate bone around the scaffold, and you want to generate a vascular system to go with it.”

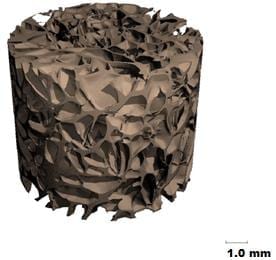

This process takes time, so ideally the growth factors would be released slowly over several days or weeks. To achieve this, the MIT team created a very thin, porous scaffold sheet coated with layers of PDGF and BMP. Using a technique called layer-by-layer assembly, they first coated the sheet with about 40 layers of BMP-2; on top of that are another 40 layers of PDGF. This allowed PDGF to be released more quickly, along with a more sustained BMP-2 release, mimicking aspects of natural healing.

“This is a major advantage for tissue engineering for bones because the release of the signaling proteins has to be slow and it has to be scheduled,” says Nicholas Kotov, a professor of chemical engineering at the University of Michigan who was not part of the research team.

The scaffold sheet is about 0.1 millimeter thick; once the growth-factor coatings are applied, scaffolds can be cut from the sheet on demand, and in the appropriate size for implantation into a bone injury or defect.

The Latest on: Bone repair

[google_news title=”” keyword=”Bone repair” num_posts=”10″ blurb_length=”0″ show_thumb=”left”]

via Google News

The Latest on: Bone repair

- Walk Aims To Put People With MS At Center Of Supporton April 28, 2024 at 9:26 am

Hundreds turned out on Sunday to take the next step in helping to find a cure for Multiple Sclerosis by participating in Walk MS St. Cloud at Apollo High School.

- Heel Spuron April 28, 2024 at 4:00 am

A heel spur, or calcaneal spur, is a bony growth of calcium deposits on the back or bottom of the heel bone that often has a hooked, pointy, or shelf-like shape. Heel spurs develop when strain or ...

- Browns’ blockbuster trade for Deshaun Watson finally complete, with Houston adding a Buckeye with the 6th and final pickon April 28, 2024 at 1:05 am

The Browns got Watson and a sixth-round pick in 2024, No. 203, which they sent to the Broncos in the Jerry Jeudy trade. They also sent a fifth-rounder from the Baker Mayfield trade with Carolina to ...

- 11 Causes of Pain on the Outer Side of Your Footon April 27, 2024 at 3:54 am

Have outer foot pain? Here are common causes of pain on the outer side of your foot, the symptoms to watch for, and how to treat it.

- See how scientists uncover 50,000-year-old fossils from California's La Brea Tar Pits where saber-tooth cats and mammoths have been foundon April 27, 2024 at 3:06 am

La Brea tar pit scientists find mammoths, saber-tooth cats, dire wolves and more in asphalt. Here's how they've uncovered fossils for over 100 years.

- 5 Ways A Cat's Purr Is Said To Have 'Healing Powers' On Their Humanon April 25, 2024 at 1:15 pm

Petting your cat can increase serotonin and oxytocin, hormones that make us feel happy and calm. Hearing your cat purr also produces those hormones, which can help to lower your stress levels. So, ...

- Shoulder surgeons should rethink a common practice, new study suggestson April 25, 2024 at 11:58 am

A common practice of shoulder surgeons may be impairing the success of rotator cuff surgery, a new study from orthopedic scientists and biomedical engineers at Columbia University suggests. The work ...

- Bone Broth Drinks Can Heal Your Gut to Boost Weight Loss: Top Doc Shares 3 Recipeson April 25, 2024 at 11:17 am

The same thing has happened to bone broth… the food that is now being lauded as “liquid gold” for its ability to repair a damaged gut, speed weight loss and transform our health. Talk about an unsung ...

- New Way to Heal Broken Bones Faster May Also Make Them 3x Strongeron April 21, 2024 at 3:29 am

A new high-tech way of healing broken bones could take less time, and also make them over three times stronger.

- Faster recovery: Irradiated plasma might help bones heal earlyon April 16, 2024 at 11:00 am

Irradiated plasma gives nonunion fractures a healing boost, which improves recovery time. Researchers treated a group of rats with a specific type of plasma called non-thermal atmospheric pressure ...

via Bing News