Ever since last summer, when Lynn Gemmell’s dog, Bela, was inducted into the trial of a drug that has been shown to significantly lengthen the lives of laboratory mice, she has been the object of intense scrutiny among dog park regulars.

To those who insist that Bela, 8, has turned back into a puppy — “Look how fast she’s getting that ball!” — Ms. Gemmell has tried to turn a deaf ear. Bela, a Border collie-Australian shepherd mix, may have been given a placebo, for one thing.

The drug, rapamycin, which improved heart health and appeared to delay the onset of some diseases in older mice, may not work the same magic in dogs, for another. There is also a chance it could do more harm than good. “This is just to look for side effects, in dogs,” Ms. Gemmell told Bela’s many well-wishers.

Technically that is true. But the trial also represents a new frontier in testing a proposition for improving human health: Rather than only seeking treatments for the individual maladies that come with age, we might do better to target the biology that underlies aging itself.

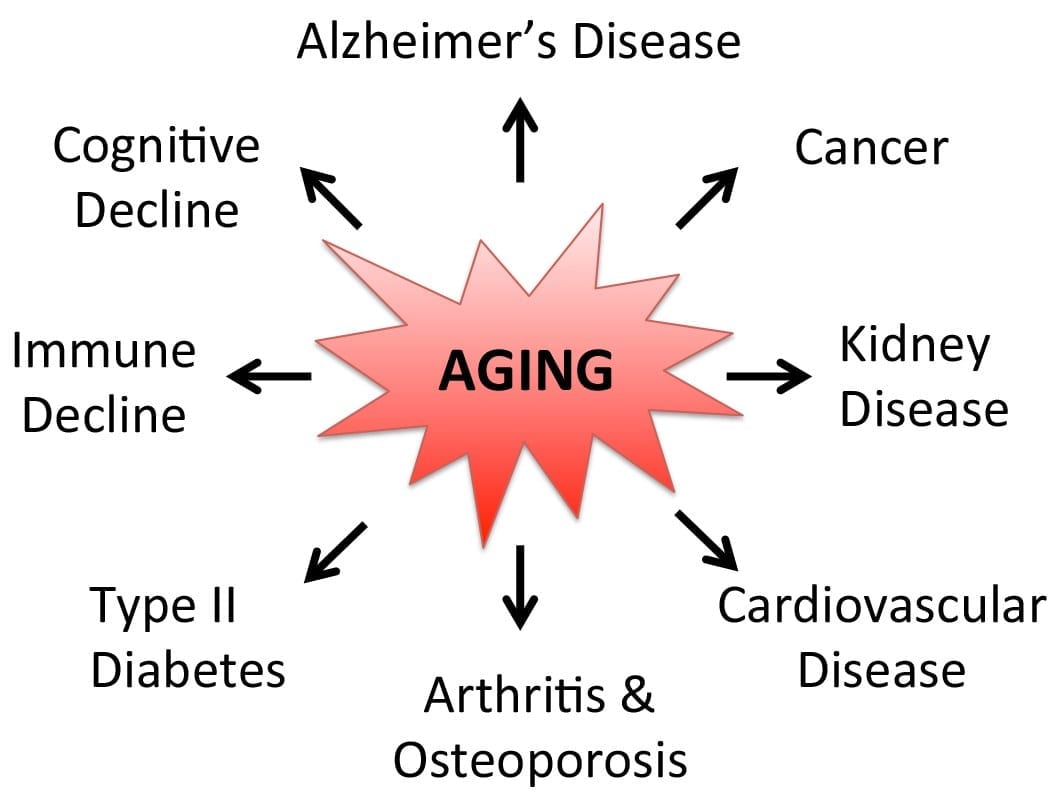

While the diseases that now kill most people in developed nations — heart disease, stroke, Alzheimer’s, diabetes, cancer — have different immediate causes, age is the major risk factor for all of them. That means that even treatment breakthroughs in these areas, no matter how vital to individuals, would yield on average four or five more years of life, epidemiologists say, and some of them likely shadowed by illness.

A drug that slows aging, the logic goes, might instead serve to delay the onset of several major diseases at once. A handful of drugs tested by federally funded laboratories in recent years appear to extend the healthy lives of mice, with rapamycin and its derivatives, approved by the Food and Drug Administration for organ transplant patients and to treat some types of cancer, so far proving the most effective. In a 2014 study by the drug company Novartis, the drug appeared to bolster the immune system in older patients. And the early results in aging dogs suggest that rapamycin is helping them, too, said Matt Kaeberlein, a biology of aging researcher at the University of Washington who is running the study with a colleague, Daniel Promislow.

But scientists who champion the study of aging’s basic biology — they call it “geroscience” — say their field has received short shrift from the biomedical establishment. And it was not lost on the University of Washington researchers that exposing dog lovers to the idea that aging could be delayed might generate popular support in addition to new data.

“Many of us in the biology of aging field feel like it is underfunded relative to the potential impact on human health this could have,” said Dr. Kaeberlein, who helped pay for the study with funds he received from the university for turning down a competing job offer. “If the average pet owner sees there’s a way to significantly delay aging in their pet, maybe it will begin to impact policy decisions.”

Learn more: Dogs Test Drug Aimed at Humans’ Biggest Killer: Age

The Latest on: Geroscience

[google_news title=”” keyword=”geroscience” num_posts=”10″ blurb_length=”0″ show_thumb=”left”]

via Google News

The Latest on: Geroscience

- High blood pressure drug called 'rilmenidine' dramatically slows aging in animalson May 1, 2024 at 2:41 pm

A drug used for high blood pressure, known as rilmenidine, may also be effective in slowing the aging process.

- Science is closing in on the frailties of old ageon April 26, 2024 at 6:00 am

Research is finding way to extend animal lifespans but regulators are still wary of treating ageing as a disease ...

- Announcing the second cohort of the Hevolution/AFAR new investigator awardees in aging biology and geroscience researchon April 23, 2024 at 7:04 am

Hevolution Foundaton and the American Federation for Aging Research announce the 2nd cohort of the Hevolution/AFAR New Investigator Awards in Aging Biology and Geroscience Research. New York ...

- Geroscience luminary, Dr. Nir Barzilai, appointed President of the Academy for Health and Lifespan Researchon April 22, 2024 at 6:28 am

Co-founder and board member at the AHLR, Barzilai has been elected to lead by fellow members of the Academy, all of whom are geroscience experts with distinguished leadership roles in the field.

- For Secrets to Extending Human Lives, Keep the Dog Aging Project Aliveon April 16, 2024 at 5:37 pm

And it’s dipping faster in the U.S. than in other high-income countries. The Dog Aging Project (DAP) is a pioneering effort in the field of geroscience – the study of the biology of aging. It’s one of ...

- Accelerated aging may be a cause of increased cancers in people under 55on April 16, 2024 at 7:13 am

Kirkland heads the Translational Geroscience Network, a research collaboration with a focus on fundamental mechanisms of aging and potential clinical interventions to prevent, delay or treat age ...

- Geroscience: the science related to agingon April 13, 2024 at 8:02 pm

Dr Daniel Belsky, an epidemiologist at Columbia University, New York (my Alma Mater), has coined the term ‘geroscience’, meaning geriatric, or related to age. Here, he has devised a novel ...

- Canine intelligence: Dogs have a general cognitive factor similar to humans, study findson April 9, 2024 at 3:31 am

The research was recently published in GeroScience. The ‘g factor’ represents a core intelligence that influences an individual’s overall cognitive performance across a variety of tasks. This concept ...

- My heartening summer school class on the new science of agingon September 3, 2023 at 12:09 am

Their endeavor goes by a name that’s not brand new but is still unfamiliar to many: geroscience. “I think we’re about to enter a golden age for geroscience,” predicted crypto entrepreneur ...

- "The goal of geroscience is life extension" (AUDIO)on September 9, 2021 at 3:15 pm

Dr. Mikhail V. Blagosklonny, M.D., Ph.D., Editor-in-Chief of Oncotarget, and Professor, at Roswell Park Cancer Institute, published "The goal of geroscience is life extension" which was selected ...

via Bing News