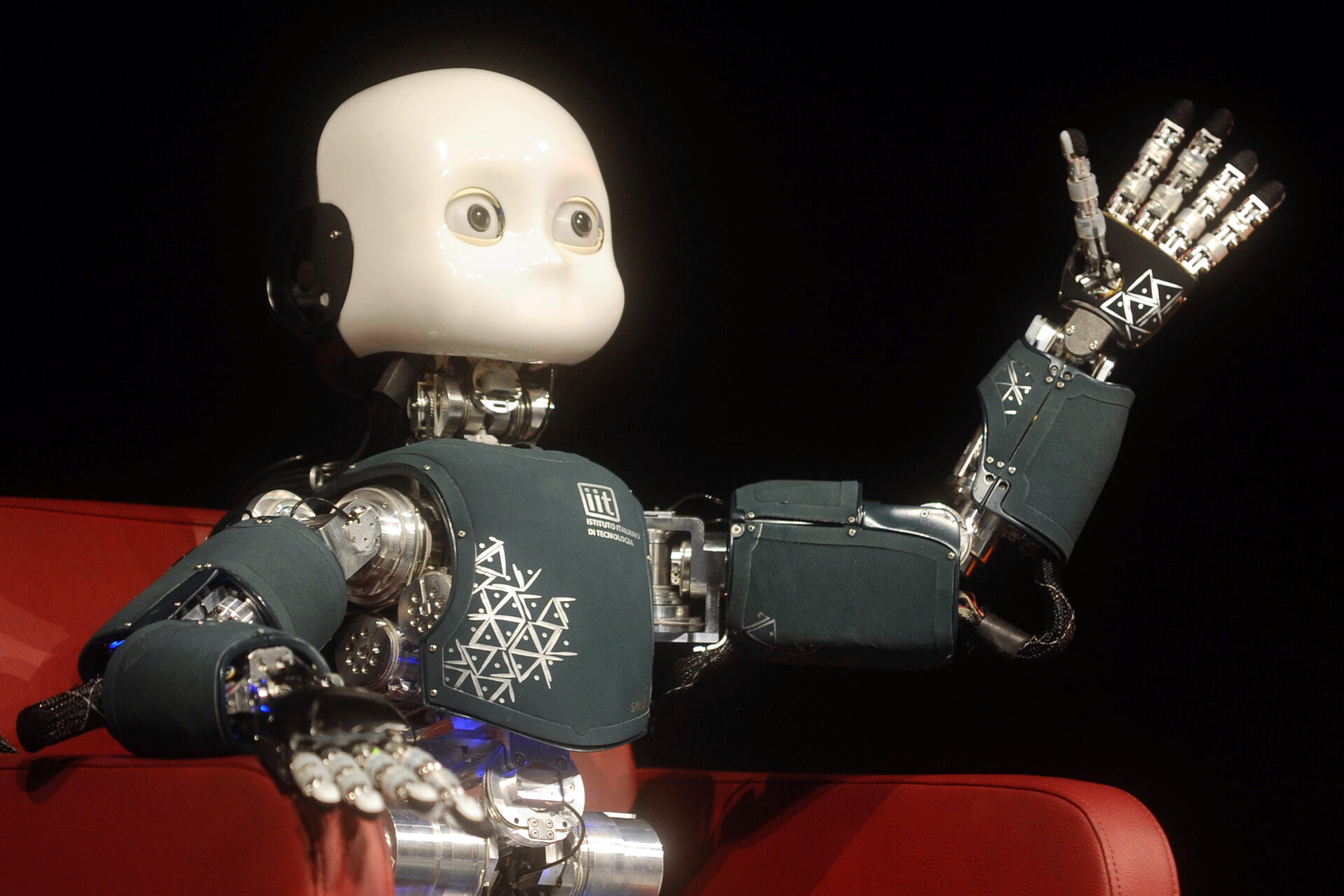

- Image via Wikipedia

IT ALL STARTED with a brawny, tattooed building contractor with a passion for exotic animals.

He was taking biology classes at City College of San Francisco, a two-year community college, and when students started meeting informally early last year to think up a project for a coming science competition, he told them that he thought it would be cool if they re-engineered cells from electric eels into a source of alternative energy. Eventually the students scaled down that idea into something more feasible, though you would be forgiven if it still sounded like science fiction to you: they would build an electrical battery powered by bacteria. This also entailed building the bacteria itself — redesigning a living organism, using the tools of a radical new realm of genetic engineering called synthetic biology.

A City College team worked on the project all summer. Then in October, five students flew to Cambridge, Mass., to present it at M.I.T. and compete against more than 1,000 other students from 100 schools, including many top-flight institutions like Stanford and Harvard. City College offers courses in everything from linear algebra to an introduction to chairside assisting (for aspiring dental hygienists), all for an affordable $26 a credit. Its students were extreme but unrelenting underdogs in the annual weekend-long synthetic-biology showdown. The competition is called iGEM: International Genetically Engineered Machine Competition.

The team’s faculty adviser, Dirk VandePol, went to City College as a teenager. He is 41, with glasses, hair that flops over his forehead and, frequently, the body language of a man who knows he has left something important somewhere but can’t remember where or what. While the advisers to some iGEM teams rank among synthetic biology’s leading researchers, VandePol doesn’t even teach genetic engineering. He teaches introductory human biology — “the skeletal system and stuff,” he explained — and signed on to the team for the same reason that his students did: the promise of this burgeoning field thrills him, and he wanted a chance to be a part of it. “Synthetic biology is the coolest thing in the universe,” VandePol told me, with complete earnestness, when I visited the team last summer.

The first thing to understand about the new science of synthetic biology is that it’s not really a new science; it’s a brazen call to conduct an existing one much more ambitiously. For almost 40 years, genetic engineers have been decoding DNA and transplanting individual genes from one organism into another. (One company, for example, famously experimented with putting a gene from an arctic flounder into tomatoes to make a variety of frost-resistant tomatoes.) But synthetic biologists want to break out of this cut-and-paste paradigm altogether. They want to write brand-new genetic code, pulling together specific genes or portions of genes plucked from a wide range of organisms — or even constructed from scratch in a lab — and methodically lacing them into a single set of genetic instructions. Implant that new code into an organism, and you should be able to make its cells do and produce things that nothing in nature has ever done or produced before.

As commercial applications for this kind of science materialize and venture capitalists cut checks, the hope is that synthetic biologists can engineer new, living tools to address our most pressing problems. Already, for example, one of the field’s leading start-ups, a Bay Area company called LS9, has remade the inner workings of a sugar-eating bacterium so that its cells secrete a chemical compound that is almost identical to diesel fuel. The company calls it a “renewable petroleum.” Another firm, Amyris Biotechnologies, has similarly tricked out yeast to produce an antimalarial drug. (LS9, backed by Chevron, aims to bring its product to market in the next couple of years. Amyris’s drug could be available by the end of this year, through a partnership with Sanofi-Aventis.) Stephen Davies, a synthetic biologist and venture capitalist who served as a judge at iGEM, compares the buzz around the field to the advent of steam power during the Victorian era. “Right now,” he says, “synthetic biology feels like it might be able to power everything. People are trying things; kettles are exploding. Everyone’s attempting magic right and left.”

Related articles by Zemanta

- City College Team Wins Admiration at Genetic Engineering Competition (sfist.com)

- ‘Building a good life’ takes on new meaning with synthetic biology (trueslant.com)

- Pentagon to Create Synthetic Organisms With Molecular Kill Switch (neatorama.com)

- Pentagon Looks to Breed Immortal ‘Synthetic Organisms,’ Molecular Kill-Switch Included (wired.com)

- Darpa’s Latest Project: Synthetic Creatures That Can Never Die [Science] (gizmodo.com)

- Genetically Engineered Machines Competition: Super Mario (scienceroll.com)

- Bacteria rewired to flash in sync (newscientist.com)

- Scientists achieve first rewire of genetic switches (biosingularity.wordpress.com)