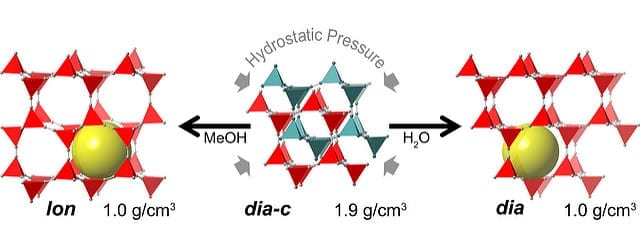

When you squeeze something, it gets smaller. Unless you’re at Argonne National Laboratory.

At the suburban Chicago laboratory, a group of scientists has seemingly defied the laws of physics and found a way to apply pressure to make a material expand instead of compress/contract.

“It’s like squeezing a stone and forming a giant sponge,” said Karena Chapman, a chemist at the U.S. Department of Energy laboratory. “Materials are supposed to become denser and more compact under pressure. We are seeing the exact opposite. The pressure-treated material has half the density of the original state. This is counterintuitive to the laws of physics.”

Because this behavior seems impossible, Chapman and her colleagues spent several years testing and retesting the material until they believed the unbelievable and understood how the impossible could be possible. For every experiment, they got the same mind-bending results.

“The bonds in the material completely rearrange,” Chapman said. “This just blows my mind.”

This discovery will do more than rewrite the science text books; it could double the variety of porous framework materials available for manufacturing, health care and environmental sustainability.

Scientists use these framework materials, which have sponge-like holes in their structure, to trap, store and filter materials. The shape of the sponge-like holes makes them selectable for specific molecules, allowing their use as water filters, chemical sensors and compressible storage for carbon dioxide sequestration of hydrogen fuel cells. By tailoring release rates, scientists can adapt these frameworks to deliver drugs and initiate chemical reactions for the production of everything from plastics to foods.

“This could not only open up new materials to being porous, but it could also give us access to new structures for selectability and new release rates,” said Peter Chupas, an Argonne chemist who helped discover the new materials.

The Latest Bing News on:

New material state

- Solid-state reaction among multiphase multicomponent ceramic enhances ablation performance, study findson May 8, 2024 at 11:45 am

Multicomponent ultra-high temperature ceramic (UHTC) has attracted much attention in research due to its superior high-temperature mechanical properties, lower thermal conductivity and enhanced ...

- Biden's Iran envoy kept classified material on personal email, cellphone that was hacked: GOP lawmakerson May 8, 2024 at 9:45 am

GOP lawmakers allege Robert Malley, President Biden’s special envoy to Iran, kept classified material on a personal cellphone and email that were later hacked.

- Why is breaking down plant material for biofuels so slow?on May 8, 2024 at 7:13 am

Tracking individual enzymes during the breakdown of cellulose for biofuel production has revealed how several roadblocks slow this process when using plant material that might otherwise go to waste.

- State may reopen Hart-Miller Island for dredged materials from planned Tradepoint terminalon May 8, 2024 at 6:00 am

Conversations are underway for Hart-Miller Island on the Chesapeake Bay to accept dredge material for the first time in 15 years.

- Parents have to update kids' access at New Orleans Public Library to comply with new lawon May 8, 2024 at 5:00 am

To comply with a new state law for Louisiana libraries, the New Orleans Public Library is requiring parents and guardians to visit a local branch and update the permissions on ...

- How a new Albemarle deal for its Kings Mountain lithium mine will help local nonprofitson May 8, 2024 at 2:49 am

The Charlotte-based company has several upcoming community meetings planned as it works to reopen the dormant mine ...

- 'Better than graphene' material development may improve implantable technologyon May 7, 2024 at 4:24 pm

Move over, graphene. There's a new, improved two-dimensional material in the lab. Borophene, the atomically thin version of boron first synthesized in 2015, is more conductive, thinner, lighter, ...

- New Mexico Supreme Court: Victim immigration history can’t be disclosedon May 7, 2024 at 2:41 pm

The state’s highest court says evidence related to an individual’s immigration status cannot be used in court proceedings in certain cases. The New Mexico ...

- Wonder Material 'More Remarkable' Than Graphene Has Medical Potentialon May 7, 2024 at 8:55 am

Borophene is already thinner and more conductive than graphene, and scientists have altered it to make it even more special.

- Transparent Materials Unlock New Possibilities for Photovoltaicson May 5, 2024 at 12:00 pm

Scientists have discovered that transparent materials can generate electricity when exposed to light, opening new avenues for optoelectronic and photovoltaic devices.

The Latest Google Headlines on:

New material state

[google_news title=”” keyword=”new material state” num_posts=”10″ blurb_length=”0″ show_thumb=”left”]

The Latest Bing News on:

New materials

- Biden's Iran envoy kept classified material on personal email, cellphone that was hacked: GOP lawmakerson May 8, 2024 at 9:45 am

GOP lawmakers allege Robert Malley, President Biden’s special envoy to Iran, kept classified material on a personal cellphone and email that were later hacked.

- Researchers 'unzip' 2D materials with laserson May 8, 2024 at 7:44 am

Researchers used commercially available tabletop lasers to create tiny, atomically sharp nanostructures in samples of a layered 2D material called hexagonal Boron Nitride (hBN). The new nanopatterning ...

- New standards for sustainable building materialson May 7, 2024 at 6:00 pm

Climate change necessitates architecture and construction industry shift towards sustainable development, design changes, planning innovations, and net zero goals to minimize environmental impacts.

- Bio-inspired materials' potential for efficient mass transfer boosted by a new twist on a century-old theoryon May 7, 2024 at 2:31 pm

The natural vein structure found within leaves -- which has inspired the structural design of porous materials that can maximize mass transfer -- could unlock improvements in energy storage, catalysis ...

- A Stunning New Material May Shrink Humanity’s Carbon Footprinton May 7, 2024 at 4:30 am

A new solution from Scotland’s Heriot-Watt University is a porous material formed in a ‘cage of cages’ structure that can capture carbon dioxide and sulfur hexafluoride faster than trees.

- New high-throughput device to unlock the potential of advanced materialson May 6, 2024 at 12:33 pm

A Birmingham researcher has developed a new high-throughput device that produces libraries of nanomaterials using sustainable mechanochemical approaches.

- New Louisiana legislation requires guardians to choose underage library material permissionon May 6, 2024 at 9:55 am

Officials with the New Orleans Public Library announced that starting Monday, May 6, anyone 17 years old with a library card will need to update their card permission.

- Synthesis of New Materials Challenge worth $Millions from TRIon May 5, 2024 at 12:23 pm

Toyota Research Institute (TRI) announces a multiyear, multimillion-dollar challenge aimed at closing the gap between recent advances in AI prediction of new materials and finding the actual “recipe” ...

- Mantle and EOS Unveil New Materials for Enhanced Performance and Sustainabilityon May 1, 2024 at 9:08 am

EOS announced a new addition to their Responsible Products portfolio: AlSi10Mg. This aluminum alloy “incorporates a minimum of 30% recycled feedstock”, making it a more sustainable material as ...

- New class of spongy materials can self-assemble into precisely controllable structureson April 30, 2024 at 8:02 am

A team of researchers led by the University of Massachusetts Amherst has drawn inspiration from a wide variety of natural geometric motifs—including those of 12-sided dice and potato chips—in order to ...

The Latest Google Headlines on:

New materials

[google_news title=”” keyword=”new materials” num_posts=”10″ blurb_length=”0″ show_thumb=”left”]