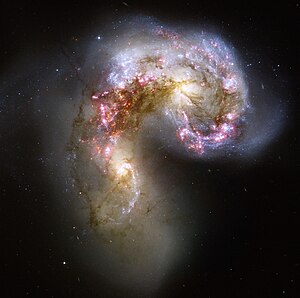

- Image via Wikipedia

IN AN age of compulsory PhDs, expensively equipped laboratories and a collaborative approach to research, astronomy is one of the few sciences still amenable to the interested amateur.

For a few hundred dollars anybody can buy a decent telescope, set it up in his garden and hope to make a meaningful contribution, such as spotting a supernova or a new comet.

Nowadays, indeed, not even the telescope is necessary. An online project called Galaxy Zoo lets amateurs do astronomy from the comfort of their own living rooms. Inspired by distributed-computing projects—which use idle time on internet-connected computers to achieve the sort of number-crunching power normally reserved for supercomputers—Galaxy Zoo employs human brainpower rather than silicon chips to make sense of the sky. The project’s 300,000 volunteers receive pictures of galaxies taken as part of the Sloan Digital Sky Survey by an automated telescope at the Apache Point Observatory in New Mexico, which they then assign to categories based on a few simple rules.

The project’s first iteration, launced in 2007, simply asked volunteers whether galaxies were elliptical or spiral-shaped, and which direction they seemed to be rotating in. It proved a huge success. Hundreds of thousands of people took part, and generally did a better job than the computer algorithms that offer the only other plausible way of crunching large amounts of astronomical data.

A newer version, launched last year, added more detailed questions. Galaxy Zoo 2, as it is called, is now yielding its first results. In a paper in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, a group of researchers, led by Karen Masters at the University of Portsmouth, in England, analysed a sample of 13,665 spiral galaxies that had been categorised by volunteers, investigating which had bars and which did not. Bars—linear clusters of stars and gas that bisect a galaxy rather like a single spoke on a wheel—are found in about 30% of all spirals, but they remain mysterious. One theory is that they are a reaction to a gravitational disturbance, perhaps from a close approach by another galaxy. Another is that the presence of a bar depends on the ratio of “normal” matter (the sort made of protons, neutrons and electrons) to “dark” matter (whose true nature is unknown, but whose existence is clear from gravitational effects) in a particular galaxy.