A blood sample could one day be enough to diagnose many types of solid cancers, or to monitor the amount of cancer in a patient’s body and responses to treatment.

Previous versions of the approach, which relies on monitoring levels of tumor DNA circulating in the blood, have required cumbersome and time-consuming steps to customize it to each patient or have not been sufficiently sensitive.

Now, researchers at the Stanford University School of Medicine have devised a way to quickly bring the technique to the clinic. Their approach, which should be broadly applicable to many types of cancers, is highly sensitive and specific. With it they were able to accurately identify about 50 percent of people in the study with stage-1 lung cancer and all patients whose cancers were more advanced.

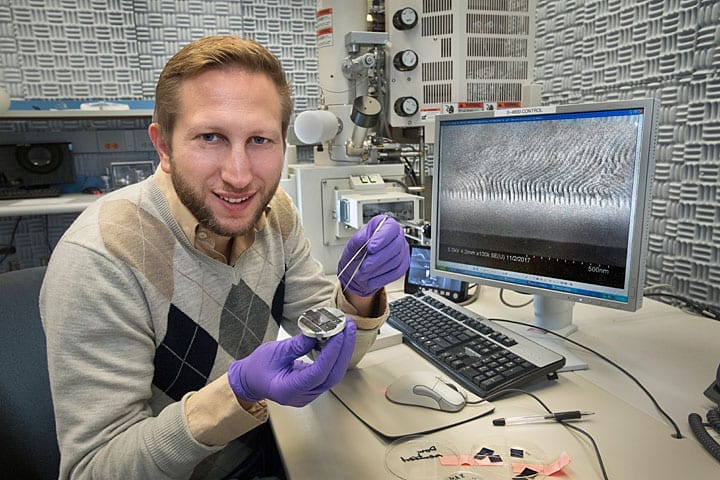

“We set out to develop a method that overcomes two major hurdles in the circulating tumor DNA field,” said Maximilian Diehn, MD, PhD, the CRK Faculty Scholar and assistant professor of radiation oncology. “First, the technique needs to be very sensitive to detect the very small amounts of tumor DNA present in the blood. Second, to be clinically useful it’s necessary to have a test that works off the shelf for the majority of patients with a given cancer.”

The researchers describe their findings in a paper published online April 6 in Nature Medicine. Diehn shares senior authorship with Ash Alizadeh, MD, PhD, assistant professor of medicine. Postdoctoral scholars Aaron Newman, PhD, and Scott Bratman, MD, PhD share lead authorship.

‘Liquid tumors’

“We’re trying to develop a general method to detect and measure disease burden,” said Alizadeh, a hematologist and oncologist. “Blood cancers like leukemias can be easier to monitor than solid tumors through ease of access to the blood. By developing a general method for monitoring circulating tumor DNA, we’re in effect trying to transform solid tumors into liquid tumors that can be detected and tracked more easily.”

Even in the absence of treatment, cancer cells are continuously dividing and dying. As they die, they release DNA into the bloodstream, like tiny genetic messages in a bottle. Learning to read these messages — and to pick out the one in 1,000 or 10,000 that come from a cancer cell — can allow clinicians to quickly and noninvasively monitor the volume of tumor, a patient’s response to therapy and even how the tumor mutations evolve over time in the face of treatment or other selective pressures.

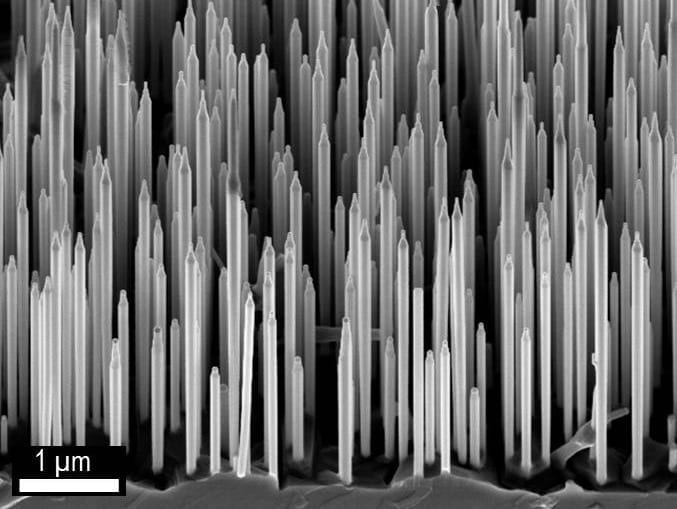

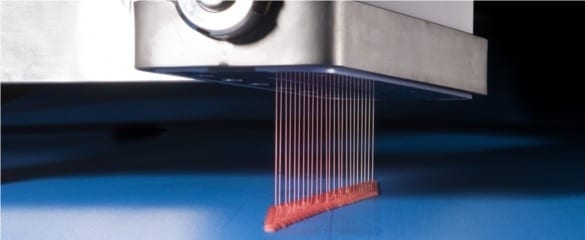

“The vast majority of circulating DNA is from normal, non-cancerous cells, even in patients with advanced cancer,” Bratman said. “We needed a comprehensive strategy for isolating the circulating DNA from blood and detecting the rare, cancer-associated mutations. To boost the sensitivity of the technique, we optimized methods for extracting, processing and analyzing the DNA.

The researchers’ technique, which they have dubbed CAPP-Seq, for Cancer Personalized Profiling by deep Sequencing, is sensitive enough to detect just one molecule of tumor DNA in a sea of 10,000 healthy DNA molecules in the blood. Although the researchers focused on patients with non-small-cell lung cancer (which includes most lung cancers, including adenocarcinomas, squamous cell carcinoma and large cell carcinoma), the approach should be widely applicable to many different solid tumors throughout the body. It’s also possible that it could one day be used not just to track the progress of a previously diagnosed patient, but also to screen healthy or at-risk populations for signs of trouble.

Tumor DNA differs from normal DNA by virtue of mutations in the nucleotide sequence. Some of the mutations are thought to be cancer drivers, responsible for initiating the uncontrolled cell growth that is the hallmark of the disease. Others accumulate randomly during repeated cell division. These secondary mutations can sometimes confer resistance to therapy; even a few tumor cells with these types of mutations can expand rapidly in the face of seemingly successful treatment.

Different from patient to patient

“Cancer is a genetic disease,” Alizadeh said. “But unlike Down syndrome, for example, which has a single dominant cause, for most cancers it’s very difficult to identify any one particular genetic aberration or mutation that is found in every patient. Instead, each cancer tends to be genetically different from patient to patient, although sets of mutations can be shared among patients with a given cancer.”

The Latest on: Cancer blood test

[google_news title=”” keyword=”Cancer blood test” num_posts=”10″ blurb_length=”0″ show_thumb=”left”]

via Google News

The Latest on: Cancer blood test

- One-two punch treatment delivers blood cancer knockouton May 1, 2024 at 12:49 pm

A novel combination of two cancer drugs has shown great potential as a future treatment for patients with acute myeloid leukaemia (AML), one of the most common types of blood cancers. A new study has ...

- Researchers identify biomarkers in blood to predict liver canceron May 1, 2024 at 11:19 am

Early detection has the potential to transform treatment and outcomes in cancer care, especially for cancers like liver cancer, which is typically diagnosed at a late stage with limited options for ...

- Two-punch treatment delivers blood cancer knockout: Study shows drug combo eradicates cancer cells in lab-based testson May 1, 2024 at 6:47 am

a laboratory head in WEHI's Blood Cells and Blood Cancer division, said. "It is these two drugs, working in tandem, that led to the highly effective killing of AML cancer cells in our lab-based tests, ...

- Prostate cancer survivor sheds light on common stigmason May 1, 2024 at 6:01 am

“Because symptoms often don't appear before the cancer is at a more advanced stage, we need to be much louder about prostate cancer awareness and utilizing early detection as the first line of defense ...

- This Bathroom Issue Is a Common Sign of Colon Cancer, According to a GI Docon May 1, 2024 at 3:25 am

In fact, by the time someone does flag blood in the stool, it may no longer be an "early symptom" of colon cancer. "Blood in the stool is a relatively late sign of colorectal cancer and does not ...

- Dallas’ Breakthrough Blood Test for Canceron April 30, 2024 at 6:00 am

Cancer Check Labs has developed a technology that can screen 40ml of blood and detect the growth of more than 200 solid tumors before symptoms occur. Modern cancer tests can be error-prone, invasive, ...

- AI tool may help detect cancer in a few minutes with a drop of bloodon April 29, 2024 at 7:57 am

An AI-powered tool may be able to detect pancreatic, gastric, or colorectal cancer with a sensitivity of 82–100% and takes just a few minutes, a new study indicates.

- Prostate Cancer Breakthrough: Urine Test Avoids Unnecessary Biopsieson April 28, 2024 at 9:57 pm

A study in JAMA Oncology reveals that MyProstateScore 2.0, a new urine test analyzing 18 genes, surpasses PSA in detecting significant prostate cancers and could reduce unnecessary biopsies by up to ...

- New blood test shows promise in early detection of ovarian canceron April 28, 2024 at 7:28 pm

A study reveals that glycoproteins in blood could be key biomarkers for early detection and staging of epithelial ovarian cancer, potentially allowing diagnosis through a simple blood test.

- Balancing hope and reality: The promise and peril of blood-based colorectal cancer screeningon April 24, 2024 at 1:30 am

A simple blood test to detect colorectal cancer sounds amazing. But unlike colonoscopy, a blood test can't remove precancerous polyps.

via Bing News