When surveillance cameras began popping up in the 1970s and ’80s, they were welcomed as a crime-fighting tool, then as a way to monitor traffic congestion, factory floors and even baby cribs. Later, they were adopted for darker purposes, as authoritarian governments like China’s used them to prevent challenges to power by keeping tabs on protesters and dissidents.

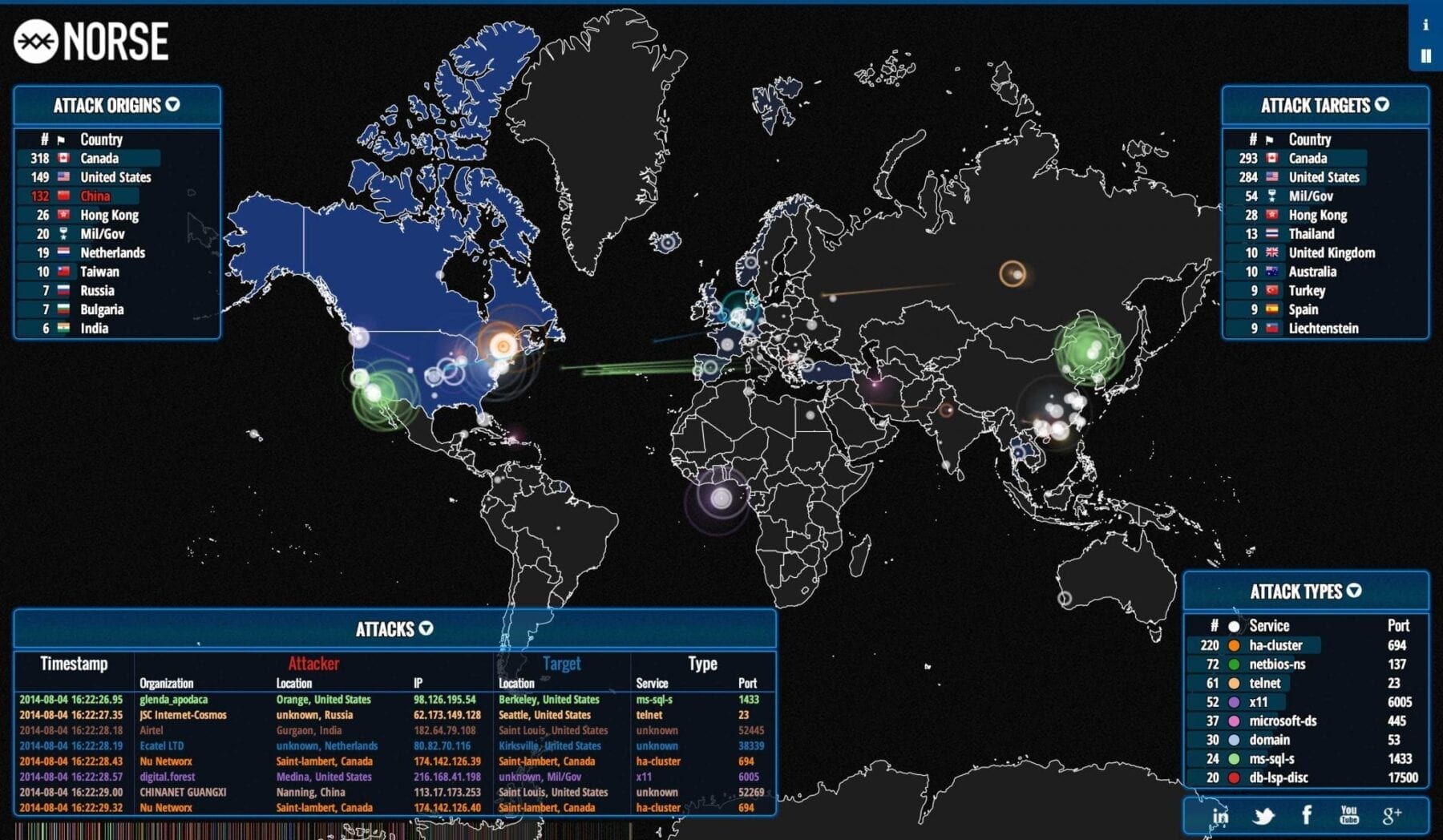

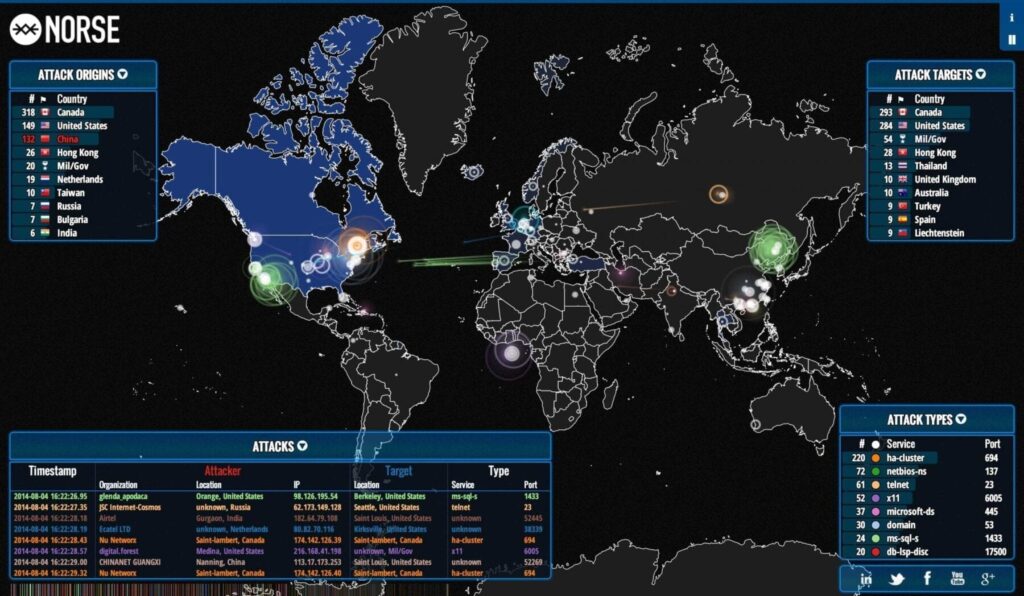

But now those cameras — and many other devices that today are connected to the internet — have been commandeered for an entirely different purpose: as a weapon of mass disruption. The internet slowdown that swept the East Coast on Friday, when many Americans were already jittery about the possibility that hackers could interfere with election systems, offered a glimpse of a new era of vulnerabilities confronting a highly connected society.

The attack on the infrastructure of the internet, which made it all but impossible at times to check Twitter feeds or headlines, was a remarkable reminder about how billions of ordinary web-connected devices — many of them highly insecure — can be turned to vicious purposes. And the threats will continue long after Election Day for a nation that increasingly keeps its data in the cloud and has oftentimes kept its head in the sand.

Remnants of the attack continued to slow some sites on Saturday, though the biggest troubles had abated. Still, to the tech community, Friday’s events were as inevitable as an earthquake along the San Andreas fault. A new kind of malicious software exploits a long-known vulnerability in those cameras and other cheap devices that are now joining up to what has become known as the internet of things.

The advantage of putting every device on the internet is obvious. It means your refrigerator can order you milk when you are running low, and the printer on your home network can tell a retailer that you need more ink. Security cameras can alert your cellphone when someone is walking up the driveway, whether it is a delivery worker or a burglar. When Google and the Detroit automakers get their driverless cars on the road, the internet of things will become your chauffeur.

But hundreds of thousands, and maybe millions, of those security cameras and other devices have been infected with a fairly simple program that guessed at their factory-set passwords — often “admin” or “12345” or even, yes, “password” — and, once inside, turned them into an army of simple robots. Each one was commanded, at a coordinated time, to bombard a small company in Manchester, N.H., called Dyn DNS with messages that overloaded its circuits.

Few have heard of Dyn, but it essentially acts as one of the internet’s giant switchboards. Bring it to a halt, and the problems spread instantly. It did not take long to reduce Twitter, Reddit and Airbnb — as well as the news feeds of The New York Times — to a crawl.

The culprit is unclear, and it may take days or weeks to detect it. In the end, though, the answer probably does not mean much anyway.

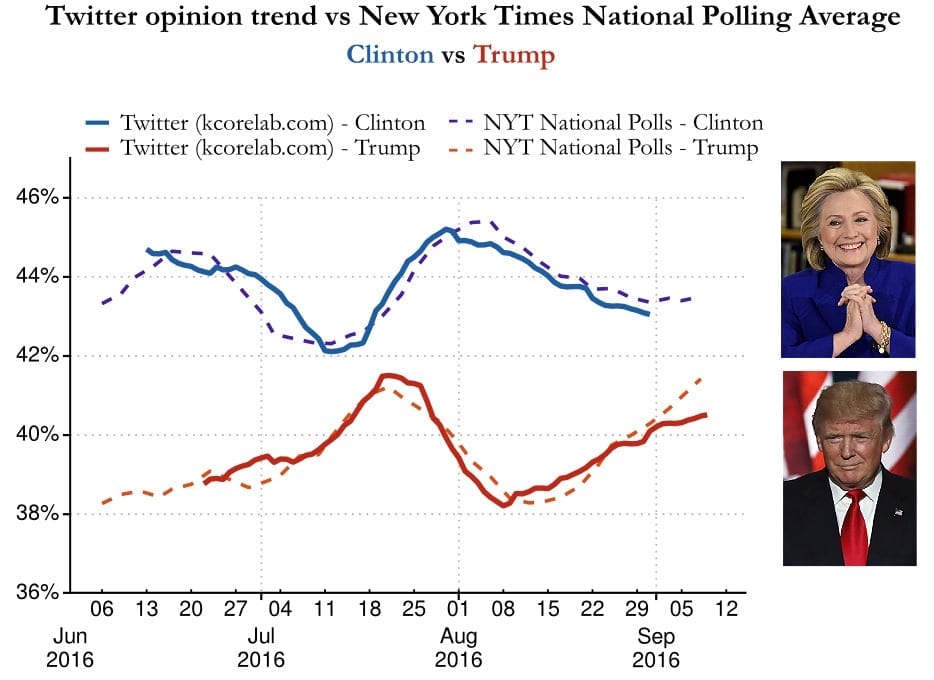

The vulnerability the country woke up to on Friday morning can be easily exploited by a nation-state such as Russia, which the Obama administration has blamed for hacking into the Democratic National Committee and the accounts of Hillary Clinton’s campaign officials. It could also be exploited by a criminal group, which was the focus of much of the guesswork about Friday’s attack, or even by teenagers. The opportunities for copycats are endless.

Learn more: A New Era of Internet Attacks Powered by Everyday Devices

You might want to also check out: Internet Security

The Latest on: Internet attacks

[google_news title=”” keyword=”internet attacks” num_posts=”10″ blurb_length=”0″ show_thumb=”left”]

via Google News

The Latest on: Internet attacks

- Ukrainian Monobank Suffers DDoS Cyber Assaulton May 2, 2024 at 8:33 am

Monobank, the largest mobile-exclusive bank in Ukraine, was hit by a significant DDoS (denial of service) attack on May 2, announced by the company’s co-founder and CEO, Oleh Horokhovskyi. Such DDoS ...

- Senators grill UnitedHealth CEO on cyber-attackon May 1, 2024 at 2:01 pm

UnitedHealth CEO Andrew Witty apologized for the cyber-attack on their subsidiary and assured lawmakers they are working to address this. “We will not rest, I will not rest, until we fix this,” Witty ...

- Cyber attack recovery could cost council £500,000on May 1, 2024 at 2:35 am

The total cost of restoring systems following a cyber attack could cost the Western Isles local authority Comhairle Nan Eilean Siar £500,000. A suspected ransomware attack in November caused ...

- The Dangerous Rise of GPS Attackson April 30, 2024 at 10:16 am

Thousands of planes and ships are facing GPS jamming and spoofing. Experts warn these attacks could potentially impact critical infrastructure, communication networks, and more.

- Innovative solutions to help thwart cyber attackson April 30, 2024 at 9:14 am

Cyber attacks are increasingly harmful, as conducting personal and business activity online has become standard practice. Corporations, governments, and other types of organizations collect growing ...

- US Cyber Agency Questioned Over Response to Massive Health Hackon April 30, 2024 at 6:00 am

A trio of US senators asked the federal government’s lead cybersecurity agency to explain its response to a February ransomware attack on an insurance company that paralyzed much of the country’s ...

- President Biden’s Latest Attack On The Economy: Smother The Interneton April 30, 2024 at 2:59 am

These controls, dubbed net neutrality, happened for a time under the Obama administration, and the results were baleful. The Trump administration scrapped net neutrality. Investment boomed, real ...

- Inside Rising Cyber Attacks: Tackling Insurance Hikes, Payment Disruptions at Nursing Homeson April 26, 2024 at 1:50 pm

Health care cyber attacks have been an ever-present threat for providers, including nursing homes. But the most recent attacks on Change Healthcare have ...

- Frontier Communications Cyber Attack Shuts Down Systems, Leaks Personal Dataon April 25, 2024 at 9:00 am

A cyber attack by a suspected cybercrime group has forced Frontier Communications, a Dallas, Texas-based optic-fiber Internet provider, to temporarily shut down its information systems to contain the ...

via Bing News