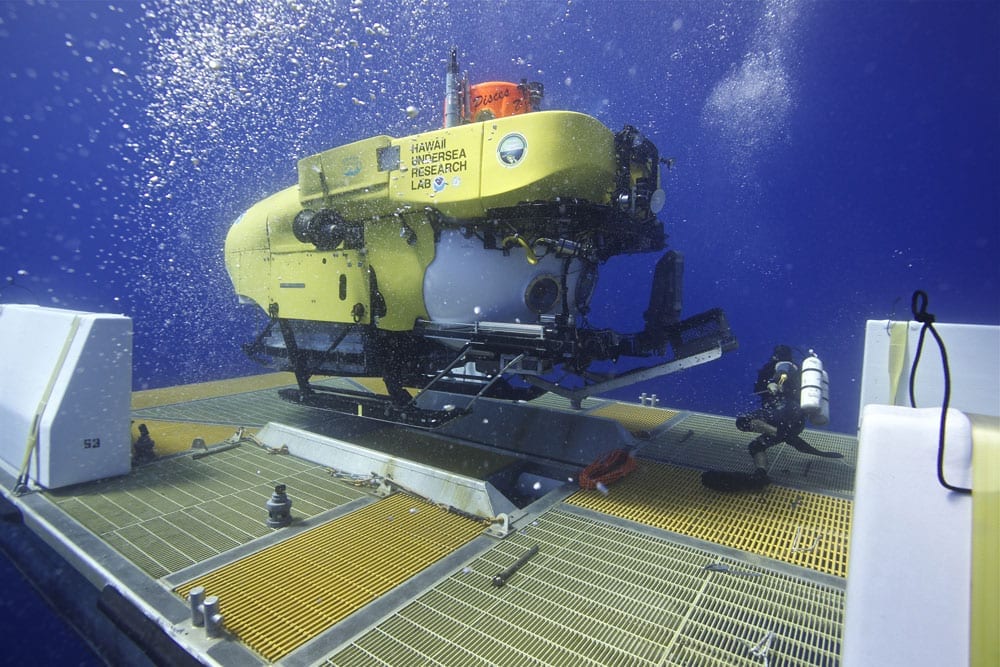

Entering the Hawaii Undersea Research Laboratory hangar is akin to stepping onto the set of a Spielberg film. The dull metal shell, perched on the Makai pier along the Windward Coast of Oahu, is nondescript, but the inside bristles with Zodiac boats and a dizzying assortment of hoists and tools, and the walls are festooned with 30 years of snapshots. At the center of it all, two 20-foot-long Pisces submarines sit atop skids like alien spacecraft, their robotic arms outstretched, beckoning for another mission.

The laboratory, part of the University of Hawaii and better known as HURL, has been the sole submersible-based United States deep-sea research outpost in the mid-Pacific since the 1980s. At its helm is Terry Kerby, perhaps the most experienced submersible pilot alive. With a crew of five, Mr. Kerby and the Pisces subs have discovered more than 140 wrecks and artifacts, recovered tens of millions of dollars in lost scientific equipment, and surveyed atolls and seamounts whose hydrothermal vents and volcanoes were unknown.

“It’s very unusual to have a facility that large and well-equipped in the middle of a large ocean basin,” said Robert Dunbar, a Stanford oceanographer. “They’ve done a remarkable thing over there, largely due to Terry’s expertise.”

But today, Mr. Kerby faces the possible mothballing of his fleet. The forces at play are the same as in many other realms of science — dwindling budgets, of course. And robots.

Robotic subs can stay down for days and reach extraordinary depths, instantly relaying their finds to scientists and an Internet-connected global audience. But they cannot go everywhere, and many scientists argue that studying the deep without direct human observation yields at best an incomplete understanding.

“You can’t replace a Terry Kerby with a robot,” said Andy Bowen, principal engineer at Woods Hole. “It’s not possible.”

At 65, Mr. Kerby is tanned and fit, thanks to daily two-mile ocean swims. He has been piloting submersibles at Makai for better than three decades, starting in the mid-1970s harvesting corals. He shifted to the University of Hawaii and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, which had bought the Makai facility to expand the nation’s deep-sea capabilities.

In 1985, Mr. Kerby found the Pisces V submersible idled in Edinburgh and persuaded the university to spend $500,000 for it. Relatively big, it could dive to 6,500 feet. “She cost $4 million to build in 1972,” he said. “And would cost $50 million to build today.”

Pisces V came with no instruction manual, but Mr. Kerby found it was highly maneuverable and could hover motionless, even in strong currents. It also operated untethered from a mother ship, allowing exploration of caves and overhangs. Coupling Pisces with the University of Hawaii’s research ship, the Ka`imikai-O-Kanaloa, and a home-built submersible platform enabled Mr. Kerby to carry out missions from 60 feet down, during surface conditions too rough for any other submersible. Mr. Kerby racked up discoveries, beginning with exploration of the Loihi seamount off Kona. Eighteen years of return missions have revealed that an area once thought dead is a vibrant world of myriad ecosystems and volcanism still shaping the Hawaiian Islands. Along Loihi and other slopes, the team discovered living corals that predate even California’s bristlecone pines.

Read more: Windows on the Deep

The Latest on: Ocean exploration

[google_news title=”” keyword=”Ocean exploration” num_posts=”10″ blurb_length=”0″ show_thumb=”left”]

via Google News

The Latest on: Ocean exploration

- 10 Misconceptions About the Oceanon May 3, 2024 at 4:29 am

It could make more ocean exploration possible, but it's still being developed. Alright, let's finish up with some misconceptions about marine animals. [Leans over to fish tank] Are you excited?

- How an Ocean Exploration Video Game Out of Monterey Bay Contributes to Scienceon May 3, 2024 at 4:01 am

Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute's FathomVerse brings you into an underwater world where you are an ocean explorer with a mission to save science. But the game is more than that: it’s helping ...

- Nintendo's Endless Ocean Game Would Be a Great VR Experienceon May 2, 2024 at 5:00 am

Commentary: Playing this chill ocean exploration game, a sequel to an older Wii title, left me wanting Nintendo to get deeper into VR already.

- FathomVerse: Harnessing AI and Gaming to Guide Ocean Explorationon May 1, 2024 at 9:00 am

FathomVerse combines immersive imagery, engaging gameplay, and cutting-edge science to help improve the artificial intelligence tools needed to study marine life and assess ocean health. A new mobile ...

- FathomVerse mobile game inspires a new wave of ocean explorationon May 1, 2024 at 9:00 am

A new mobile game launching today allows anyone with a smartphone or tablet to take part in ocean exploration and discovery. Welcome to FathomVerse. Now available for download on the App Store and ...

- Endless Ocean: Luminous review: chill underwater adventure runs out of airon April 30, 2024 at 6:00 am

Endless Ocean: Luminous ’ calming ocean exploration and lovely multiplayer components wear thin due to slow progression hooks that turn every aspect of it into a long chore. With tons of features from ...

- Endless Ocean Luminous Reviewon April 30, 2024 at 6:00 am

So it’s incredibly disappointing that Endless Ocean Luminous’ take on one of the most exciting settings on Earth is boring, tedious, and downright aggravating. This deep sea diving adventure’s ...

- Newest luxury submersible offers ocean explorers champagne and blackjackon April 25, 2024 at 7:33 am

The submersible will offer eight passengers and a pilot a panoramic view of the water world surrounding them. In a video released this week highlighting the submersible, Triton described the 660/9 AVA ...

- Pacific sleeper shark: Study analyzes ‘possibly the largest predatory fish' in oceanon April 22, 2024 at 12:11 pm

Researchers at NOAA Fisheries created a “one-stop shop" for information critical to conserving the Pacific sleeper shark.

- Dive Into Profits: 3 AI Ocean Exploration Stocks to Watch for Massive Returnson March 26, 2024 at 3:00 am

With current deep-sea resource-extracting companies turning to artificial intelligence (AI), a new nexus of AI ocean exploration stocks has formed. While metal extraction has yet to begin ...

via Bing News